The Question Mark Résumé: Living and Working in the Space between Professional Systems

By J. Owen Matson, Ph.D.

This post is far too long for LinkedIn, which is reason enough to post it there as a bit of professional theater. The following reflection presents a question, or perhaps the shape of one, that doesn’t sit comfortably inside a platform—or a job description. I’ve been told more than once that my background is hard to categorize, which is another way of saying it doesn’t lend itself well to bureaucratic taxonomies. We are trained to write résumés as if we were composing still lifes: tidy, legible, and pre-approved for institutional digestion. But what we call a career narrative is always already framed—by structures we didn’t choose, histories we didn’t write, and economies that would very much like us to mistake formatting for meaning.

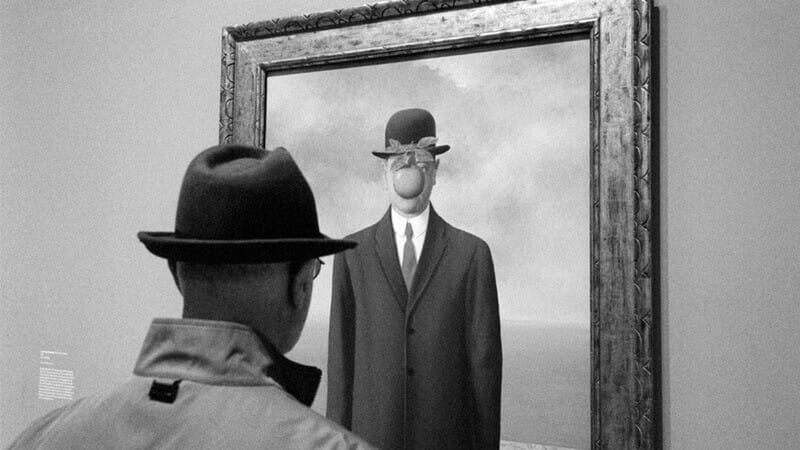

There’s a photograph I find myself returning to. A man in a coat and bowler hat stands before Magritte’s The Son of Man. He stares into a painting that seems to reflect him—same coat, same hat—but with one notable exception: the figure’s face is blocked by a floating apple. It’s a visual gag, of course, but also a lesson in ideology. The more he looks, the less he sees. Identity, here, is not something to be uncovered, but something artfully withheld—conjured and concealed by the same gesture. I see it as a photo of a painting, a kind simulacrum, a copy of a copy that, in the case, depicts,, foregrounds, and performs its on mis-recognition. It's kind of like a résumé, really.

The Resume as Narrative

To be professionally read is, more often than not, to be misunderstood with great conviction. One is presented like an abstract painting in a boardroom: vaguely intriguing, possibly valuable, and ultimately best interpreted in terms of asset class. You resemble what the frame expects—well enough to be slotted into a taxonomy, but not so well as to avoid triggering mild ontological distress. The outlines are recognizable; the contents, regrettably, are not.

The résumé—surely one of the more inventive literary forms of late capitalism—pretends to narrate a life by reciting its job titles in reverse. It is a document so committed to narrative coherence that it regards contradiction as a formatting error and epistemological tension as a gap in employment. Its job is not to illuminate but to launder: to scrub out the ambiguities, eccentricities, and minor existential crises that make up a working life, and replace them with “impact.”

It would be heartening to report that my career resists this logic. In fact, it rather ignores it entirely. A doctorate in English from Princeton, a decade in classrooms, a sideways lurch into learning science, followed by various misadventures in EdTech strategy, instructional systems, and product design. On paper, it reads less like a career and more like the minutes of a very confused planning meeting. But paper, as ever, is not to be trusted. It can carry a theory of quantum mechanics or a Subway coupon with equal gravity.

Over the years, I’ve acquired the sort of professional reputation usually reserved for avant-garde theatre or early Deleuze. Too academic for business, too managerial for academia, too theoretical for implementation, and—according to one cheerful performance review—“too philosophical to inspire confidence.” These labels tell us little about the work and rather a lot about the cultural prejudices of the institutions doing the labeling.

The real issue, if we can still use such earnest terminology, is not whether one has been “recognized.” That word performs far too much ideological heavy lifting. Recognition suggests a kind of visual certainty, as though meaning might float unimpeded to the surface if only the lighting were better. But in practice, recognition is the act of squinting at someone else’s reflection in your own conceptual mirror and deciding it looks just familiar enough to count as knowledge.

If this is a personal grievance, it's one that speaks to a broader epistemological design flaw. And it becomes most visible in industries like educational technology—spaces that claim to be interdisciplinary but prefer their convergence frictionless, credentialed, and ideally monetizable. Here, complexity is an aesthetic, not a principle. Dialogue is encouraged so long as everyone agrees. And cognitive diversity is celebrated until it threatens the quarterly roadmap.

What the English Ph.D. doesn’t show at first glance

A Ph.D. in English from Princeton tends to come with a ready-made aura. One is assumed to be a literary theorist with a shelf full of Derrida and a half-finished novel in the drawer—an ornament of high culture whose natural habitat is a seminar room, not a product sprint. In business settings, this background reads a bit like turning up to a software launch in a cravat. People assume you’ve taken a wrong turn somewhere near a wine bar.

But English, at least in its more unruly moments, has always been a kind of intellectual stowaway—crossing borders under false papers, looting methods from philosophy, anthropology, semiotics, and psychoanalysis without bothering to return them. It was never really about novels. Novels were simply the contraband. The real traffic was in meaning, mediation, affect, structure. What English offered was not content but the scandalous proposition that form matters—that how something appears might be as consequential as what it says. It turns out that many of the questions I was trained to ask in literary theory are now being posed—less elegantly, more earnestly—in places like EdTech, though usually with fewer footnotes and considerably more Post-its.

Take “user experience.” In a former life, we called this phenomenology. We asked: What is an experience? How is it structured? What makes it coherent—or incoherent—for the subject living through it? We examined the temporality of attention, the rhythm of perception, the bodily orientation of the self in space. Husserl wrote whole volumes trying to understand the difference between recollecting a sound and hearing it unfold in time. In UX, this becomes: “Can we make the modal window less annoying?”

The problem is not that UX lacks intellectual rigor—it’s that it actively disavows it. Under the pressure of speed, scale, and commercial imperative, phenomenology is flattened into interface psychology. Experience becomes a quantifiable sequence of tasks to be frictionlessly completed, not a textured field of perception to be understood. Questions of embodiment, narrative, and temporal unfolding are replaced by A/B tests and user flows, as if consciousness were just a funnel with a loading state.

Where phenomenology once asked what it means to dwell in a world, UX now asks how quickly we can get someone out of one app and into another. It rewards legibility over richness, coherence over contradiction. What once required an account of time-consciousness now hinges on scroll depth. One begins to suspect that the ultimate goal is not experience at all, but its engineered disappearance—a world so “intuitive” it no longer needs to be noticed.

This is not, of course, to sneer at usability. No one wants to wrestle with a broken interface just to access their lesson plan. But when ease becomes the only value, we begin to design for a subject without depth—what phenomenology might have called a user without a world. The “seamlessness” so beloved in UX circles often means not the removal of friction, but the erasure of reflexivity. You’re not meant to notice the system. You’re meant to glide through it, ideally without wondering who built it, what assumptions it encodes, or what kinds of thinking it permits—or forecloses.

So yes, I studied literature. But I also studied epistemology, cognitive science, posthumanist ethics, and the history of how bodies and systems become sites of meaning. My dissertation had as much to do with how brains and machines communicate as it did with books. It asked how understanding emerges—not only in the text, but in the interface, the ritual, the infrastructure.

The transition to EdTech, then, wasn’t a leap. It was more of a reformatting—from MLA to Figma, from prose to prototype. The questions remained. They just had to wear different shoes. The move into learning design and product strategy wasn’t a departure from theory. It was theory under constraint—translated into deadlines, stakeholder alignment, and the cheerful tyranny of the roadmap. But the question remained unchanged: How is knowledge shaped? By what system? Through what affordance? And to whose benefit?

Yes, I can teach Hamlet. But my dissertation also traced the intersections of 19th-century physiology, situated learning theory, posthumanist ethics, and distributed cognition. It was a study in how meaning is made—on the page, in the body, and in emergent technologies. As it happens, this is also what educational technology claims to be interested in, albeit with more dashboards and fewer references to Kant.

The transition into EdTech didn’t feel like a leap. The questions remained more or less the same. They simply had to get dressed up in new terminology and stripped of their dialectical instincts. But if my background equipped me to ask these questions, it may also have over-equipped me for the cultural conditions in which they now circulate. In many institutional settings—especially those where product timelines are mistaken for epistemologies—thought is not simply undervalued. It’s treated with active suspicion.

There is, in such spaces, a curious allergy to abstraction. Ideas are welcomed, provided they know their place. Theory is acceptable only in retrospect—once the product has shipped, the metrics are clean, and the money has changed hands. Until then, to reflect too deeply is to risk being labeled impractical, or worse, “academic.” The assumption being that ideas get in the way of action, as if there were some pristine realm of action unsullied by concepts, values, or interpretation.

In this environment, asking foundational questions—What is learning? What forms of attention are we designing for? What kinds of knowledge do our systems privilege or preclude?—can seem not only inconvenient but vaguely subversive. These are the kinds of questions that gum up a roadmap. They resist being reduced to key results. They introduce a time lag where acceleration is expected. They smell, frankly, of trouble.

So while my academic training honed the very instincts needed to think critically about design, systems, and meaning-making, it also instilled habits of inquiry that don’t always play well in cultures built around execution. (A term that, incidentally, once referred to state-sanctioned killing.) To “execute” is to act with finality, not with doubt. But education—like thought—is a domain where doubt is not a weakness, but a method.

My work, then, is not just about bringing theory to practice. It’s about resisting the artificial severance of the two. It’s about holding space for recursion in a culture that fetishizes linearity, and insisting that critical thought is not an obstacle to action, but one of its most ethical forms.

Misrecognition isn’t personal

When people skim the hybrid ledger of my professional experience—a catalogue that has included literary theory, epistemology, pedagogy, learning science, and the odd foray into strategic operations—they often respond with the kind of expression one reserves for modern art or obscure dietary supplements: something intriguing is clearly going on, but no one’s quite sure whether it belongs in a museum or a meeting. I am frequently assessed as too conceptually saturated for the practical concerns of execution, yet somehow not sufficiently pragmatic to pass as an efficient operator, as though to possess ideas were itself a liability, or worse, a form of aesthetic clutter. The assumption is that I must either be allergic to outcomes or unaware that the term “deliverable” is no longer metaphorical. There is, in such judgments, a remarkable talent for contradiction: I am either too immersed in systems to understand how they work, or too attentive to context to be trusted with clarity.

The result is a rather elastic social positioning, in which one is alternately perceived as mystifying or mildly dangerous, depending largely on whether one has spoken recently. The smile that appears perfectly ordinary in most settings is now read as knowing, the pause as provocative, the question as subtext, and the effort to clarify as a surreptitious attempt to undermine. These interpretive gymnastics are not, it must be said, the result of paranoia but of a cultural landscape in which ambiguity is viewed less as an invitation to thought than as a threat to momentum. In such environments, one is not evaluated on what one says, exactly, but on the potential energy of what one might be about to say, which is frequently deemed excessive. The professional imagination, like most bureaucratic systems, has a remarkably low tolerance for latency.

Yet it is precisely within these moments of conceptual misfire and perceptual unease that hybridity, in the genuine sense, begins to emerge—not as the seamless integration of perspectives so beloved in corporate mission statements, but as the flickering failure of categories to contain the complexity they pretend to name. Hybridity, as I’ve come to understand it, does not announce itself in the language of innovation decks or thought leadership slides; it appears instead in the minor dissonances of professional life, in the refusal of a profile to cohere, in the quiet panic provoked by an unexpected question about first principles.

This landscape of partial recognition and disciplined misreading is not alien to me. It is, in many ways, the native terrain of literary study. One might even say that English departments were the original sites of structured misunderstanding, long before it became the domain of product strategy. For years, my work consisted in tracing the moments when texts fail to disclose themselves neatly, when language resists the meanings assigned to it, when readers, like stakeholders, mistake familiarity for understanding. The conceptual idioms now repurposed for corporate usage—hybridity, recognition, alterity, opacity—were not for me managerial tropes or branding exercises. They were the coordinates of an intellectual landscape dedicated to examining how meaning is produced, how authority is performed, and how culture organizes what it allows to be visible and what it works, often very hard, to misrecognize.

If I have grown fluent in navigating professional spaces that are unsure what to do with me, it is not because I have learned to simplify my thinking, but because I have spent a great deal of time studying how institutions behave when confronted with that which does not quite fit. And if I sometimes sound as though I am interpreting the meeting rather than merely attending it, that is only because I have been trained to notice when a system, like a sentence, begins to signal more than it can comfortably say.

When those same dynamics appear in organizational life—the panic that sets in when ambiguity dares to enter a meeting uninvited, the sudden allergic reaction to nuance during quarterly planning, the faint dread that flickers across the room when someone asks what the word engagement actually means—they do not arrive as surprises. I have seen these scenes before, albeit in more elegantly typeset editions. The meeting that cannot metabolize uncertainty is structurally identical to the novel that fears its own irony. The roadmap that abolishes complexity bears a striking resemblance to the syllabus that only permits questions with predetermined answers. The conversation that insists on consensus while quietly policing dissent is not unlike the undergraduate essay that claims Hamlet is simply indecisive. These are not anomalies. They are texts. And, like all texts, they are structured by assumptions that resist their own exposition.

To move between academic theory and professional domains is not, as it is sometimes imagined, an act of translation from one discrete dialect into another, but a form of reading—of treating systems, policies, workflows, and PowerPoint decks as the ideological forms they are, thick with formal structure, rhetorical intention, and implicit hierarchy. One does not merely learn to restate concepts in more palatable language; one learns to trace how meaning is shaped by organizational aesthetics, how decisions are framed as natural when they are, in fact, authored, and how authority is performed through the careful choreography of tone, gesture, and bullet points. It is not, strictly speaking, a question of communication. It is an epistemological mode with a long and respectable lineage, one that refuses to confuse fluency with insight or performance with knowledge. It is not meant to reassure the structure. It is meant to reveal it.

Of course, this kind of analytic attention is not always welcomed with open arms. To recognize the architecture of thought within a team offsite, or to note the semiotics of a whiteboard exercise, is sometimes mistaken for indulgence, or worse, obstruction. Precision is confused with pedantry. Ambiguity is mistaken for vagueness. The desire to pause and name the frame is interpreted not as intellectual care but as a kind of latent rebellion. It is the kind of misunderstanding one grows accustomed to in environments where speed is mistaken for efficiency and where the preferred intellectual posture is a confident shrug. The discomfort is not personal. It is symptomatic of a professional culture that values clarity as long as it does not disturb hierarchy, and action as long as it does not require thought.

What my training offered was not a set of rarefied abstractions, but a discipline of interpretation. It did not prepare me to neutralize tension, to soothe contradictions, or to convert structural dilemmas into upbeat bullet points for stakeholder alignment. It trained me, rather, to dwell within complexity without rushing toward false resolution, to read power not as the exception but as the organizing principle, and to understand that meaning, like strategy, is always delivered through a medium—and that medium is never innocent.

The illusion of prestige

And then, of course, there is the matter of Princeton, which tends to enter the conversation early—if not through declaration, then through inference, tone, or a certain involuntary tightening of the room’s atmosphere. It hovers somewhere between credential and cautionary tale, evoking prestige in one register and presumption in another, and managing, with great efficiency, to serve simultaneously as proof of excellence and as evidence of potential disconnection from anything resembling the so-called real world. Before one has uttered a syllable, the institution has already spoken on one’s behalf, usually in a plummy accent and with questionable politics.

The irony, of course, is that the path that led me to that hallowed Gothic cloister did not originate in any of the usual corridors. I attended public schools of the unfashionable variety—the sort that had more metal detectors than microscopes—and spent four years in community college, which is a bit like attending a university inside a parking structure. I worked full-time through much of my undergraduate education, and part-time through the rest, acquiring not just degrees but an intimate knowledge of mop handles, cash registers, and the fragile psychology of customers who believe that retail workers are paid to absorb their cosmological disappointment.

My father, a high school teacher by profession and a scholar by temperament, became a university professor only as I was finishing college, by which point I had already learned that academic authority was not inherited but constructed, often under fluorescent lighting. My mother was a psychiatric nurse with a formidable talent for diagnosis and an even more formidable tolerance for bureaucracy. There were no legacy admissions, no private Latin tutors, no well-placed family friends in publishing or tech or whatever sector currently defines social mobility. What there was, instead, was time, labour, exhaustion, and an almost reckless commitment to the value of learning, even when the institutions built to house it seemed increasingly perplexed by the human condition.

This background is not, as some politely suggest, an “offset” to a prestigious résumé, as though one were simply balancing out an overly rich sauce with a dash of vinegar. It is not the narrative footnote that makes the main plot more palatable. It is the structure, the scaffolding, the very condition of possibility for the rest of the story. My presence at Princeton, improbable as it may have seemed to others, was not a clerical error or an act of benevolent gatekeeping. It was the outcome of an accumulation—of work, curiosity, endurance, and that peculiar form of optimism that flourishes in unpromising circumstances and takes the shape not of slogans but of persistence.

This is, perhaps, why misrecognition doesn’t simply bruise, but lingers—though I try, when I can, not to let it harden into grievance. Because misrecognition is not merely something done to us by others in their rush to categorise. It is a deeply human habit, a form of narrative economy in which we mistake the surface for the story because we have been taught, over and over, that stories ought to follow a recognizable plot. It is, at root, a failure of epistemic imagination—a refusal to entertain that what stands before us might be neither anomaly nor exception, but simply the result of a different arrangement of effort, time, and inherited difficulty.

And if, like me, you have spent four years navigating community college while working to keep the electricity bill from becoming metaphorical, you learn very quickly that many of the templates we are asked to inhabit were not designed with your life in mind. They are, in fact, quite bewildered by your presence, and do their best to reduce you to something more manageable. But once you see how the template works, how it edits as it categorizes and flatters as it excludes, you acquire the one thing more powerful than fitting in: the ability to read the system without mistaking it for the world.

EdTech isn’t one field—it’s a convergence with unresolved tensions

EdTech, despite its fondness for presenting itself as the site of a grand synthesis—where the timeless virtues of education meet the sleek efficiencies of modern technology—is less an alliance than a collision, in which incompatible epistemologies are forced to cohabitate under the watchful eye of a product manager. But the more sobering truth is that there is no longer a pristine pedagogical sphere waiting to be invaded by platform logic. Education itself, in its institutionalized form, long ago internalized the very managerial rationality that EdTech now claims to have imported. The bureaucratization of learning, the obsession with measurable outcomes, the translation of inquiry into key performance indicators—these are not recent afflictions. They are the operating system of contemporary education, often resented by teachers, yes, but enforced all the same with the kind of procedural regularity that would make a procurement officer blush.

What we encounter, then, is not a clash between two competing value systems, but a convergence between two arms of the same apparatus. On one side, you have the technologists, speaking in the patois of product-market fit, user flows, and scalable impact. On the other, you have educational institutions, equally fluent in the grammar of dashboards, learning outcomes, efficiency mandates, and institutional branding. Both sides participate in the same fantasy: that knowledge can be rendered legible to management, that pedagogy is improvable by throughput, and that the affective, ethical, and interpretive dimensions of learning can be distilled into design principles without remainder. The only real difference is that in the university, the PowerPoint has footnotes.

To speak of education as recursive, reflective, and hospitable to ambiguity is not, then, to describe its current practice so much as to recall its earlier aspirations, which now persist largely in faculty handbooks and the increasingly apologetic language of grant proposals. What we now call “learning” is often less a process of discovery than a logistical arrangement: a choreography of deliverables distributed across terms, semesters, and modules, designed primarily to be evaluated, optimized, and reported upward. And when this already administered structure is paired with the operational tempo of product cycles, the result is not corruption but amplification—a kind of epistemic karaoke in which the form of education is preserved while the content is replaced by an investor pitch.

This is not a lament for lost purity. I have worked long enough in EdTech and academia alike to know that nostalgia is often the first refuge of people unwilling to do institutional analysis. What interests me is not the restoration of some mythical golden age of learning, but the question of how knowledge behaves once it enters systems designed to manage it. I have watched cognitive science repurposed to increase “stickiness” on learning platforms, and watered-down echoes of affect theory conscripted into the service of brand strategy. I have seen pedagogical frameworks smoothed into onboarding flows, and entire histories of critical inquiry converted into moodboards for the modern LMS. It is not the presence of theory that concerns anyone, but its half-life once it has been filtered through marketing.

In this environment, translation is no longer adequate. What is required is a diagnostic literacy—a capacity to read across infrastructures and to understand how questions of learning are now posed within the architectures of operational control. To reflect under these conditions is not an act of delay or dithering, but of resistance: a refusal to accept that systems integration is the same as understanding, or that alignment must always mean agreement. The real work lies not in reconciling education and technology, but in seeing how both are entangled within a wider epistemological regime—one that values motion over meaning, legibility over complexity, and output over thought.

The illusion of neutrality hides asymmetries in knowledge

Within most EdTech companies, education tends to occupy a curious liminal position—present enough to decorate the mission statement, but rarely so central as to interfere with the actual running of the business. One finds it nestled uneasily among the more muscular dialects of the professional caste: Engineering, Product, Marketing, Strategy, and Finance, each speaking with the confident briskness of people who believe they are building something real. The org chart, that modern-day map of institutional metaphysics, retains its familiar geometry: the Director of Product here, the VP of Growth there, all situated as if the object of the enterprise—be it glucose monitors, dating apps, or the acquisition of knowledge—were more or less interchangeable, provided the metrics are sound and the slide deck fonts properly kerned.

The prevailing structure flatters itself on being agnostic, which is to say, committed to no particular ontology of its own while happily enforcing several. It is modular, disciplined, and ostentatiously efficient, with a fondness for workflows that resemble nutritional labels and a deep suspicion of anything that cannot be tracked in dashboards or narrated in bullet points. But agnosticism, despite its marketing appeal, is not neutrality. It is simply a style of belief with plausible deniability. In practice, it comes equipped with an entire epistemology of its own—one in which knowledge is presumed to be modular, abstractable, and ideally shippable in fortnightly sprints. Within this schema, education is quietly evacuated of its historical density and recast in friendlier, more monetizable terms: pedagogy becomes “delivery,” curriculum is flattened into “content,” and learning, that most unpredictable of human endeavours, is rebranded as “engagement,” a term equally beloved by product designers and cult leaders.

Even when the word “education” is given a seat at the table, it tends to arrive wearing borrowed clothes. Instructional expertise is often assumed to reside in anyone who has spent time in a classroom without running from it screaming, while administrative experience is treated as pedagogical insight on the grounds that both involve seating charts. A passing reference to Bloom’s Taxonomy is deployed like an API call—precise, authoritative, and deeply divorced from its historical or theoretical context. The result is not simply the misrecognition of individuals, which, while demoralizing, is at this point expected. It is the systematic evacuation of a field’s complexity in favour of a version that can be safely indexed in a product backlog and queried during onboarding.

This is not merely a professional oversight; it is an epistemic loss. For when organizations decline to engage with hybrid or disciplinary complexity—when they filter out what does not conform to their established legibility—they do not merely overlook people like me. They overlook the chance to think differently about learning itself, to treat it not as a logistical inconvenience in need of smoothing, but as a site of ambiguity, friction, and potentially radical transformation.

And this, of course, is the irony so rich it practically writes its own satire. Because what English, in its unfashionable but still ferociously intelligent moments, actually prepares one to do is precisely what this industry needs but cannot quite describe without breaking into hives: to read systems of meaning in context, to follow language as it circulates through power, to parse the subtle difference between what is said and what is meant, and to dwell—without panic—in the awkward spaces where things do not align. In other words, to ask not simply what works, but what it means for something to work, and for whom, and to what end.

Recognition isn’t the goal. But how we see—that matters.

The professional world, in its infinite managerial wisdom, tends to treat disciplinary difference as little more than an accent—something one can smooth out with a few LinkedIn courses and a well-timed pivot into “stakeholder alignment.” One speaks of style, of communication norms, of domain fluency, as if the problem were one of lexical variation rather than fundamental epistemological misalignment. The notion that someone might actually think differently—because they have spent decades immersed in forms of inquiry that don’t immediately translate into product frameworks or executive dashboards—is quietly disturbing to a system that prefers difference only in its cosmetic variety.

The discomfort, when it arrives, is rarely dramatic. It creeps in sideways, like a colleague who enters a meeting late and pretends not to be. A certain hesitation in the room. A suspicion that one is circling the question rather than answering it. Traits acquired through sustained engagement with ambiguity—attunement to contradiction, comfort with dissonance, a studied refusal to mistake confidence for clarity—are politely misread as signs of indecision, or worse, of not being “aligned.” Reflexive humility, which in some traditions is treated as the height of intellectual virtue, is here mistaken for insufficient assertiveness in a performance review. The very capacities that allow one to navigate complexity are recoded, with exquisite irony, as liabilities within systems built to conceal how complex they really are.

Yet the failure of recognition is never simply a failure of recognition. It is the symptom of a deeper incapacity: the inability of institutional frameworks to perceive that which does not already mirror their assumptions. One is not overlooked because of what one is, but because of what others have not been trained—or permitted—to see. And to respond to that misperception with personal grievance is, while emotionally understandable, philosophically naïve. The fault, as Marx might put it, lies not in our selves but in our systems.

The real work, then, is not to retrofit oneself into the available taxonomies, but to expose their insufficiency. It is not to clamor for inclusion in a structure that was never designed to understand you, but to draw attention to the terms of understanding themselves. This is not a campaign for personal validation, though that is a temptation with no shortage of takers. It is a commitment to a different kind of epistemic labour: the patient refusal to reduce what does not yet make sense, the willingness to stay with the illegible, and the quiet insistence that opacity is not failure but a form of resistance to premature clarity.

One does not always manage it, of course. It is far easier to reach for the familiar language of impact, outcomes, and value propositions, to find a temporary refuge in the comforting metrics of alignment. But the more difficult task—the one worth attempting, even at the cost of career advancement or being uninvited from strategy offsites—is to maintain a stance of principled intransigence. Not belligerence, not contrarianism, but a disciplined attentiveness to what cannot yet be named, and a willingness to listen precisely when one is most inclined to explain. It is not, as they say in product meetings, a solution. But then again, neither is the status quo. And at least this one doesn’t require a JIRA ticket.

The best collaborators expect to be surprised

The most generous people I have had the good fortune to work alongside—whether in a classroom tracing the melancholy of King Lear or in a business meeting gamely pretending that a dashboard redesign constitutes innovation—share a habit of mind so unassuming it almost escapes notice. They expect, in a quiet but persistent way, to be surprised. Not surprised in the pedestrian sense of encountering an unforeseen variable on a spreadsheet, but surprised in the epistemological sense: disturbed, gently or otherwise, by something that does not fit their model of how the world works. They move not through certainty but through curiosity, which, in corporate environments especially, is a rarer and far more useful resource than confidence.

Such people do not confuse familiarity with understanding, nor do they imagine that agreement is the natural endpoint of thought. They do not treat difference as an inefficiency to be ironed out, nor do they panic at the prospect that someone else might see the same situation through a lens not pre-approved by the quarterly roadmap. Their generosity lies not in sentiment but in stance: they listen with the explicit hope that their interpretive frame might be insufficient, that their categories might prove leaky, that their tidy metaphors might not hold up under pressure. It is, in short, the opposite of managerial optimism. It is not that they assume things will go well, but that they suspect reality is more interesting than their plan.

This is the disposition I learned, not in a workshop on active listening or a seminar on leadership communication, but in the largely thankless practice of teaching undergraduates to read carefully. I never asked students to furnish me with the correct interpretation, as if the poem were a particularly coy customer support ticket. I was listening instead for what escaped the frame—for the stray remark, the unexpected turn, the moment when language started to say more than the prompt had planned for. I was not after accuracy, but insight. And insight, like most worthwhile things, arrives late, out of order, and wearing the wrong shoes.

The best professors I encountered—as well as the best leaders I have worked with since—shared this sensibility. They were not interested in being affirmed, though they tolerated it with good grace. What moved them was the sudden emergence of thought, the crack in the surface where something new might appear. Their authority was not diminished by being interrupted; it was animated by it. They understood that mastery, for all its comforts, is often just a fancier name for closure. And what they craved instead was the opposite: the invitation to reopen the question.

What I failed to realize, at least at first, was that this was not merely a pedagogical technique. It was not a clever trick to make the classroom livelier or the meeting more inclusive. It was a metaphysical commitment—a way of inhabiting thought and relation that takes difference not as a problem to be solved, but as the condition of anything worth knowing in the first place. It is not a style. It is not a tactic. It is, in the oldest sense of the word, a philosophy. And if that orientation occasionally makes one appear impractical in rooms obsessed with outcomes, or slow in spaces obsessed with speed, so be it. Better to be misread for thinking too much than celebrated for never thinking at all.

Whole student learning—and the work of working with others

So no, this isn’t a plea to be seen more clearly, as if recognition were simply a matter of polishing the lens. It is, rather, a reflection on how recognition itself operates—on the rickety machinery through which we come to perceive others, misperceive them just as swiftly, and then congratulate ourselves on having done our due diligence. Recognition, in practice, is less a moment of mutual understanding than a kind of bureaucratic shorthand for comprehension, a swift internal memo from the unconscious that says: “File under X, proceed accordingly.” And like most memos, it often gets the details wrong.

There is, in educational circles, a phrase that has gathered considerable institutional charm: “whole student learning.” The term is meant to suggest a vision of the learner as more than a GPA, as someone whose growth includes not only cognitive prowess but emotional nuance, cultural context, and the occasional existential crisis. It is a noble gesture, and like many noble gestures, it frequently collapses under the weight of its own abstraction. For beneath the banner of “whole student learning” there often lurks the very same logic it purports to resist: the desire to capture, categorize, and ultimately optimize the subject, preferably in time for next quarter’s outcomes report.

But there is a deeper truth embedded in the slogan, if we are willing to look slantwise at it. To take the idea of the “whole student” seriously is not to pretend we can know the learner in total, like a curriculum map with well-labeled exit points. It is to acknowledge, with a kind of principled humility, that there is always more to a person than we can perceive—more than they can perceive, for that matter—and that the task of education, if it is anything at all, is not to consolidate identity but to crack it open. To listen not only for what confirms our categories, but for what scrambles them. To treat the learner not as a bundle of competencies, but as a scene of emergence.

And that sensibility, as quaint as it may sound in rooms adorned with OKRs and roadmaps, is not confined to the classroom. It is equally at home in a strategy meeting, a hiring decision, a feedback conversation. What we call “fit”—that golden criterion of organizational culture—is so often less about talent than about epistemic comfort. It tells us less about who someone is than about the boundaries of what we are willing to understand. It is, at times, little more than the institutionalization of our own interpretive laziness. The real work, then—the harder, slower, and considerably more worthwhile work—is not to make everyone legible. It is to dwell, as long as we can bear it, with what exceeds our grasp. To treat the limits of our frameworks not as errors to be patched, but as invitations to think again. And again. And again. And allow something new to emerge from the contradictions that fracture and defamiliarize our habitual and blind assumptions about the order of things.

Because if education teaches us anything worth knowing, it is that knowledge never arrives fully dressed. It shows up rumpled, resistant, and often late. And if we insist on recognizing only what already fits, we may miss the very thing we claim to be looking for.