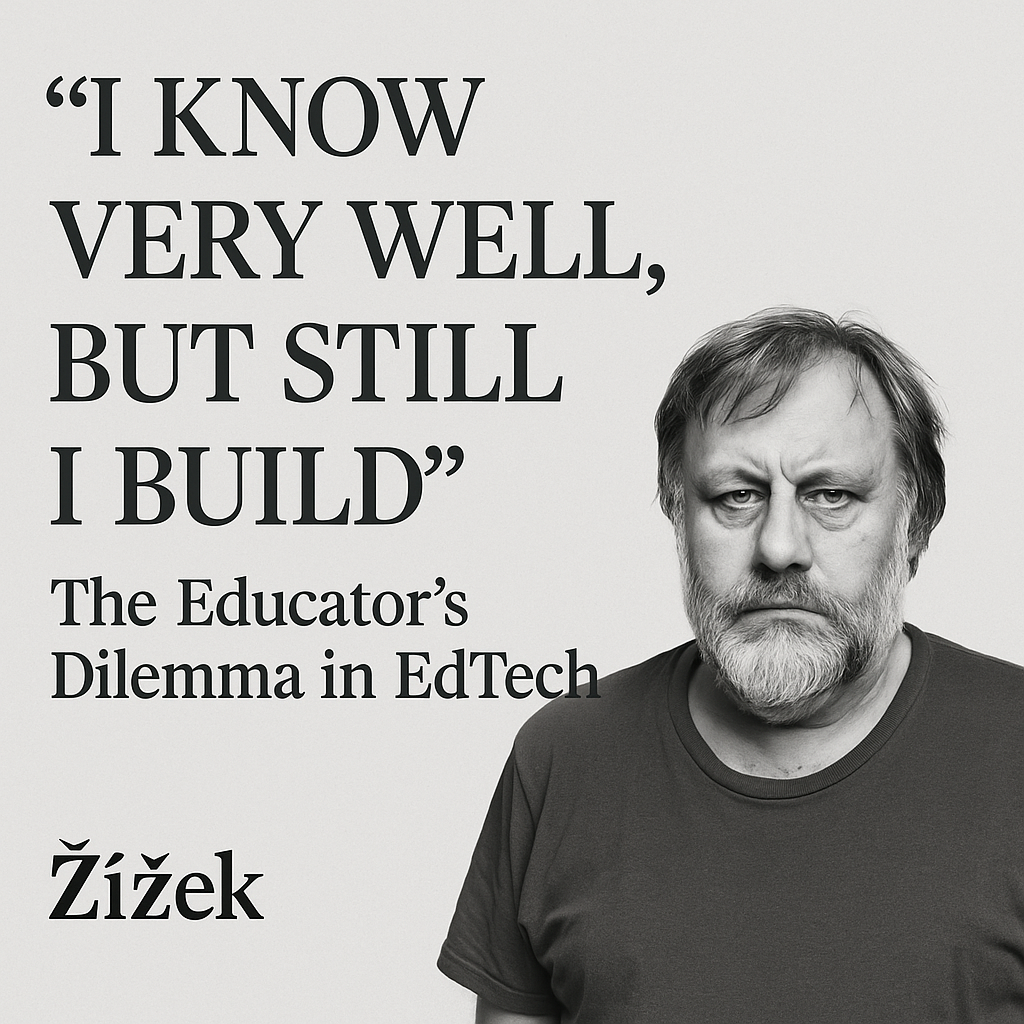

The Ideology of EdTech: On Žižek and the Irony of Building What You Don’t Believe In

Educators in EdTech often face a disorienting dilemma: they’re asked to build systems they don’t fully believe in, under conditions that quietly discourage critique. The result is a professional reality marked by contradiction—one where educators must act in support of practices that run counter to what they know about how students actually learn.

The philosopher Slavoj Žižek offers a useful frame for understanding this. For Žižek, ideology isn’t about being fooled. It’s about believing in something we already know is untrue. That belief doesn’t live in conviction—it plays out in action. We participate not because we’re persuaded, but because we’re expected to act as if we are. The system doesn’t require sincerity; it requires performance.

Think of money. We know it has no intrinsic value—it’s a socially constructed fiction. Yet we believe in it because the system demands it.

EdTech operates on the same logic: we build what we know is broken.

In this sense, Žižek’s ideology is fundamentally ironic. Irony names the gap between appearance and reality. Ideology doesn’t suppress that gap—it demands we live inside it. The appearance of belief is maintained even when the reality is obvious.

This is the position many educators in EdTech find themselves in: compelled to translate flawed assumptions into specs, dashboards, and talking points.

I recently wrote an essay on Rob Cottingham’s cartoon Emotional Distance Education, which stages this irony with uncanny precision. A man on a date declares, “I’ll have you know I’m very empathetic. I’ve watched every Khan Academy video on human emotion. Twice.” The joke isn’t that he’s wrong. It’s that he’s earnest. He mistakes repetition for transformation—content consumption for care. And in doing so, he becomes the perfect subject of platform ideology.

When everyone performs belief in something they know is untrue, the only ones who stand out are the ones who actually believe it. They become the joke. Like Michael Scott or David Brent in The Office, or the characters in a Christopher Guest film, they aren’t funny because they’re lying—they’re funny because they’re sincere.

They fully inhabit the logic everyone else is merely performing.Their sincerity reveals the system better than any critique could.