The Credential Is the Joke: Empathy, Platform Pedagogy, and the Irony of Knowing in a Cartoon by Rob Cottingham

By J. Owen Matson, Ph.D.

Abstract

This essay examines the single-panel cartoon Emotional Distance Education, attributed to Rob Cottingham, as a cultural artifact that stages a profound critique of platform-based epistemologies of learning. Through close visual and conceptual analysis, the essay argues that the cartoon satirizes the substitution of quantifiable performance for relational understanding, revealing how platform logic reconfigures learning as repetition, credentialism, and behavioral rehearsal. Drawing on theories from Gert Biesta, Simon Critchley, Jacques Rancière, and feminist epistemology, the essay shows how the cartoon’s irony, asymmetry, and silence dramatize the erasure of embodied and affective knowledge. In doing so, it frames the cartoon as a diagnostic of the techno-educational corporate complex—a system that deconstructs the very conditions of learning while continuing to demand its performance. The cartoon becomes, paradoxically, both symptom and critique: a joke whose structure exposes the ideological absurdity of education under the metrics of platform governance.

1. The Declarative Scene

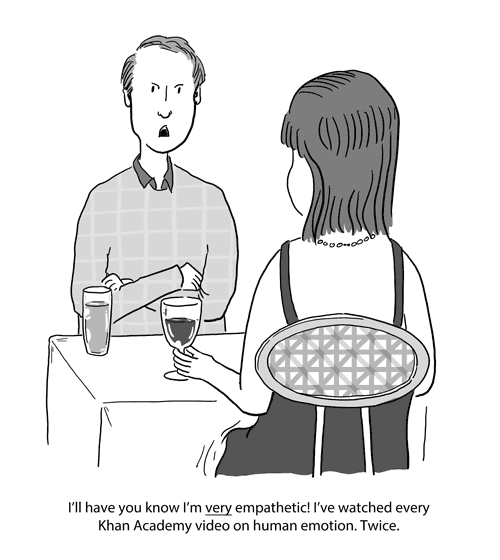

In 2012, Canadian cartoonist Rob Cottingham published a single-panel cartoon titled Emotional Distance Education. The image depicts a man and a woman seated across from each other at a small table, suggesting a date setting. The man leans forward, his expression earnest and slightly defensive, declaring: “I’ll have you know I’m very empathetic! I’ve watched every Khan Academy video on human emotion. Twice.” The woman, holding a glass of wine, sits back with a neutral or perhaps skeptical expression, offering no verbal response.

At first glance, the cartoon’s humor seems simple—a man mistakes learning about emotion for having emotional capacity. But the joke quickly sharpens. The incongruity between what the man says and what the situation shows points not to an individual error but to a broader epistemological confusion. His statement is offered as proof, even credential. He has completed empathy. He has done the modules. Twice. What kind of world must exist for this to count as evidence? What epistemic structure underwrites the idea that watching videos—on a platform, asynchronously, twice—is equivalent to having empathy, or being empathetic? The cartoon offers a paradox: what is visible (the repetition, the effort, the content mastery) becomes the very marker of what is absent (attunement, response, presence). The humor is diagnostic—it dramatizes the failure of the statement to match the reality it attempts to certify.

This episode marks a breakdown in the machinery of understanding, a scene where the failure lies in the system itself rather than in the exchange of messages. The cartoon draws us in through humor, yet its force lies in the conditions it quietly exposes—the scaffolding that renders such reasoning intelligible. What appears comic unfolds as a study in epistemology. It stages a world in which the protocols of learning have been rewired. Here, assertion now parades as intimacy, and consumption substitutes for the labor of transformation. The image invites more than a passing smirk. It gestures toward the architecture that renders misunderstanding routine, even structurally affirmed. The humor succeeds through familiarity. His gestures—consuming, mimicking, announcing—resemble the rituals of credentialing that dominate contemporary life. He completes the process and trusts in its authority. Everything around him seems to agree.

The man’s declaration reveals more than a stray misjudgment; it traces a cultural habit in which learning aligns itself with visible outcomes and endorsed achievements. In this context, “twice” functions as a credential, a marker of diligence and mastery within a system that values repetition and completion over genuine understanding. The cartoon thus critiques an educational paradigm where emotional intelligence is treated as a skill to be acquired through standardized modules, rather than a relational capacity developed through lived experience. Moreover, the woman’s silence and body language underscore the failure of this approach. Her lack of engagement suggests that true empathy cannot be demonstrated through self-proclaimed expertise alone. It requires presence, attunement, and an openness that cannot be simulated or certified.

In this light, Cottingham’s cartoon serves as a satirical commentary on the limitations of distance education and the commodification of emotional intelligence. It challenges us to question the efficacy of systems that prioritize content delivery over meaningful human connection, and to reflect on the ways in which genuine empathy resists quantification.What is being lampooned here, then, extends beyond interpersonal cluelessness. It gestures toward an entire epistemic order—one that renders his statement intelligible, even institutionally coherent.

Thus this single-panel cartoon functions as a concentrated satire of platform-era pedagogy. The cartoon’s humor depends on a shared recognition of how learning has been redefined by repetition, performance, and credentialism. Through close analysis, the essay shows how the cartoon stages a critique of platform logic across multiple dimensions: its quantification of learning (Section 2), its displacement of embodied transformation by behavioral performance (Section 3), its erasure of relational knowledge through epistemic illegibility (Section 4), and its use of irony as a form of epistemological exposure (Section 5). It then examines how the cartoon’s gendered asymmetries illuminate the structural exclusions of dominant educational epistemologies (Section 6), how its spatial design aestheticizes disembodiment and flattening (Section 7), and how it reveals platform governance as a mode of subject formation rather than instructional delivery (Section 9). In the final sections, the essay traces the contradictions of credentialism and the self-deconstructing nature of educational legitimacy under platform capitalism—arguing that the cartoon stages, performs, and ultimately critiques the epistemology of its own world.

2. Credentialism and the Logic of Quantitative Learning

The word “twice”—seemingly throwaway, casually boastful—reveals a recursive epistemology at the heart of the cartoon’s satire. It is offered as proof, as credential, and even as assurance. Yet in the moment of its assertion, “twice” discloses the system’s failure. It signals the quiet displacement of a pedagogy grounded in understanding by one structured around repetition itself. More precisely, the reiteration, posed as confirmation, reveals an underlying absence—a compensatory gesture that seeks to resolve the very lack it exposes. Repetition here performs as both symptom and substitute—index of mastery and marker of its deferral. This is the point at which the epistemology of quantification begins to implode. Platform logic ascribes value to repetition as evidence of diligence and forward motion, tallying effort in modules completed, videos viewed, minutes accrued. Yet within pedagogical life, repetition acquires meaning only in relation to encounter. As Gert Biesta reminds us, education requires interruption—an event that unsettles the learner’s frame of reference and resists absorption into existing patterns. The recursive return to content may reflect diligence, but without encounter, it leaves only the residue of comprehension deferred.

The cartoon captures this paradox precisely: the man has watched the videos on empathy—twice—and still failed to attune, to respond, to be present. His repetition is not deepening but flattening. And yet, he presents it as evidence of authority. The structure of his claim is psychologically compensatory: the more he senses his own lack, the more fervently he reasserts the credential. His citation of repetition is not a confession of failure, but a deflection from it. This dynamic exposes a kind of deconstructive logic within the epistemology itself: the more one tries to “learn” through platform repetition, the more the system reveals its incapacity to produce learning as transformation. What emerges is not cumulative knowledge typically associated with learning, but a recursive loop where structure converts the breakdown of understanding into a data point of continued compliance.

This recursive temporality aligns closely with Jonathan Crary’s account of 24/7 time and Mark Fisher’s description of capitalist realism: a system in which change is no longer structurally possible, and where stasis is recoded as motion. Under this logic, even learning’s failure is rendered productive—as long as it remains visible, trackable, and repeated. The question of whether understanding has actually occurred becomes irrelevant. What matters is that the attempt can be documented, and that the user remains engaged. Thus, repetition becomes both the mark of absence and its ideological concealment. The more one repeats, the more one is rewarded—not for transformation, but for staying in the loop, for repetition itself. What “twice” really reveals is that the pedagogical structure cannot recognize rupture, cannot value uncertainty, and cannot allow for the very conditions that make learning possible.

The cartoon crystallizes this tension. The man’s performance follows the system’s logic precisely—it realizes its structure without remainder. He is caught in a recursive feedback loop where learning is defined by visible accumulation rather than internal change. His authority is entirely surface-bound. And in that surface, we see the epistemic wound that platform pedagogy must constantly cover over: the wound of a system that can only ever simulate understanding, never support it.

3. Performance vs. Embodiment

While the man speaks of empathy, his body tells a different story. His posture—rigid, arms crossed, torso angled slightly forward—conveys an architecture of closure. His arms cross tightly, torso pitched forward, brows arched in a posture of offense rather than invitation, an architecture of closure. This is not the relaxed posture of someone attuned to the emotional presence of another. This disjunction between language and posture marks one of the cartoon’s most incisive visual ironies. And in this, the cartoon lays bare a core tension within platform epistemology: the substitution of verbal performance for embodied transformation.

Morever, this is not the performance of someone uncertain about their learning, but the indignation of someone who believes—sincerely, adamantly—that repetition guarantees transformation. His declaration emerges with the certainty of one who has internalized the platform’s grammar of mastery: views accrued, modules completed, content covered—twice. The cartoon stages this affective dissonance with surgical precision. His body carries conviction, but not relation; intensity, but no attunement. And herein lies the deeper irony. Platform education has done more than fail to teach empathy. It has cultivated the belief that empathy has already been achieved. The result is not mere absence, but dissociation—a system that bypasses embodied experience while convincing its subjects they have absorbed it fully.

Learning, in this model, does not occur in the body. It is imagined as an informational overlay—something one acquires, stores, and performs upon command. Yet this is precisely what theorists like John Dewey and Gilles Deleuze challenge. For Dewey, learning is situated and experiential—a mode of embodied adaptation within an environment. It cannot be detached from context, nor from the organism’s embedded relation to the world. Dewey’s learner does not accumulate facts; they undergo experience. Deleuze, similarly, offers the notion of learning through conjugation: the idea that learning happens not through mastery of preexisting propositions, but through bodily alignment with difference—through exposure to that which one cannot yet name. In this view, learning is pre-linguistic and affective before it is conceptual. It involves becoming attuned to rhythms, constraints, affordances—forces that resist immediate integration.

The man in the cartoon has yet to conjugate in the Deleuzean sense. Instead, he repeats. He has remained at the level of the declarative, the already-given. He has consumed content, but his body lingers outside its movement. His empathy floats, detached—positioned as an object of cognition rather than a mode of responsiveness. This is the systemic failure being rendered visible. Within a platform epistemology, performance overrides transformation. The appearance of learning gains priority over its actual effects. The learner is called to affirm achievement, whether or not change has transpired. The body fades from view as a site of epistemic registration. And yet, in the cartoon, it reappears—unwittingly, as the counter-evidence. The visual irony turns on this disjunction: he speaks of empathy, but the body lags behind, still engaged in proving what it has yet to encounter.

This tension remains unresolved within the logic of delivery-based learning. The man’s failure emerges through architecture rather than personal defect. He has been taught to treat empathy as a discrete object—something to accumulate, describe, and display, abstracted from lived experience. The cartoon, however, reveals another possibility. It asks us to read the body as a site of epistemological resistance—a surface where the limits of disembodied learning become legible.

Importantly, this reading does not suggest that digital or asynchronous learning is inherently disembodied, nor that it cannot produce the kinds of transformative encounters articulated by Biesta, Dewey, or Deleuze. What the cartoon critiques is not digital education per se, but the dominant epistemology that underlies much of its implementation: a feedback loop in which what is perceived as learning (watching videos) is shaped by what is delivered as learning (watching videos)—and both are made legible only through quantitative metrics. In other words, the satire does not target the medium of digital learning, but the reductive model of pedagogy it tends to reproduce. The man does not simply voice the quantifiable logics of platform-based instruction—he actually believes he has learned. Within this logic, learning cannot fail to occur—it can only fail to be demonstrated, and demonstration is always measured by performance. He accepts the visible structure of repetition and completion as sufficient proof of internal change. This belief is not a misunderstanding—it is the product of a system that equates learning with throughput, attention with accumulation, transformation with visibility.

And yet, in an ironic twist, the cartoon itself performs what the video could not. In staging this failure, it enacts an alternative pedagogy—one grounded in affect, irony, visual contradiction, and the performative staging of relation. It does not tell us what empathy is; it makes us feel its absence. The cartoon thereby becomes an instance of what Biesta might call interruptive pedagogy: it creates a moment of recognition through dissonance. It is not content to be absorbed, but a scene that asks to be lived through.

The cartoon, in other words, does more than visualized the lack of embodied learning. More powerfully, it mobilizes an affective pedagogy as content itself. The cartoon refrains from delivering information in any conventional sense. There is not didactic delivery of information. Instead, it orchestrates a relational experience composed through absence, dissonance, and visual irony. It shows the limits of a particular epistemic framework rather than asserting them outright, unsettling the logic it renders by embedding it within a scene of estrangement. One might describe this as a dramatization of expectation failure—though the failure belongs elsewhere. It is the viewer who encounters this breach, who discovers that the signals long associated with empathy—content delivered, phrases repeated, emotions performed—have drifted from the practice they once implied. Learning, in this instance, arises through displacement. In this moment, learning does not result from exposure, but from a shift in position: the viewer moves, is moved, or at least glimpses the edge of a system that cannot move anyone at all. And in that flicker of awareness, the cartoon quietly expands the very concept of learning it appears to lampoon.

4. The Woman’s Silence and the Epistemology of Absence

If the man in the cartoon embodies the logic of platform pedagogy—its performances, repetitions, and visible outputs—then the woman across from him represents something else entirely. Her role is not to correct, challenge, or instruct, but to mark the limits of the epistemology being enacted. She does so not through verbal expression—not through the didactic, but through its absence in silence. Her refusal to respond becomes the most powerful gesture in the scene—not because it withholds validation, but because it exposes the illegibility of relational knowledge within a system that recognizes only performance. Here the unseen woman operates, not as the subject of irony, but as the structural horizon of the joke itself, and the bearer of an alternative epistemological position.

Across from the man, the woman sits still. Her body is composed, her hand lightly cradles a wine glass, her gaze diverted slightly away from him. She does not interrupt, confirm, or refute. She offers no performance of recognition. She listens—but does not respond. But this silence is not passive; rather it is pointed. What the cartoon stages through her restraint is not a lack of participation but a refusal to comply with the terms of the exchange. She does not enter the grammar of citation, performance, or credential. She does not mirror the man’s need for validation. Instead, her silence becomes a form of critique—a quiet withdrawal from a logic of relationality that has been made unrecognizable.

Under platform epistemologies, silence is a failure to engage. Inaction is a data gap. Ambiguity is an error state. These systems require feedback, affirmation, visible indicators of learning or response. What cannot be seen or marked is excluded from recognition. And yet, in Cottingham’s cartoon, it is the woman’s absence of legibility that reveals the most. She becomes the condition of the scene’s intelligibility: not by what she says, but by what she refuses to say. Her silence does not signify a void; it foregrounds the inadequacy of the man’s claim. In this sense, her presence enacts what we might call a pedagogy of the invisible. She performs a kind of epistemic opacity that resists being captured by the metrics of knowledge performance. The man’s statement falls flat not because she corrects him, but because he cannot reach her—cannot locate her within the terms of a learning model that only recognizes outcomes, not relations.

The platform logic dramatized here has no capacity for unquantifiable difference. Relational understanding—subtle, affective, situational—is rendered illegible within a system of structured delivery and repeatable assertion. The woman does not reject the man; she escapes the field in which he believes his performance should land. And in this, she becomes the marker of a different kind of knowing: one that does not announce itself, does not credential itself, but nonetheless holds the authority of attunement. Her silence is the cartoon’s most powerful line. It marks the epistemological limit of a system that cannot make sense of the knowledge she inhabits. She is not the object of the joke. She is its frame. It is through her quiet distance that we recognize the absurdity of the man’s position—and the absurdity of the system that produced it.

This quiet distance also exemplifies what Jacques Rancière might call a disruption of the distribution of the sensible—the normative arrangement of what can be seen, heard, and recognized as meaningful within a given order. In the cartoon’s pedagogical economy, the man’s performance is fully sensible: it is visible, vocal, credentialed. The woman’s silence, by contrast, does not register as engagement. But this misrecognition is precisely what reveals the cartoon’s epistemological critique. Her refusal to respond—her illegibility—is not a deficit. It is a redistribution of the perceptual field that exposes the narrowness of the system’s terms.

Rancière’s politics of education similarly resists the presumption of pedagogical hierarchy. Where traditional models assume a gap between those who know and those who do not, Rancière insists on the radical equality of intelligence. The woman in the cartoon embodies this refusal of hierarchy. She does not correct, educate, or respond within the man’s frame. Her silence is not the silence of submission, but of emancipated non-participation. She withdraws not from the scene itself, but from the script it presumes to follow. In this light, the cartoon’s humor becomes a kind of Rancièrian pedagogy. It stages a collapse in the logic of instruction and authority—not to offer a better teacher or clearer message, but to show the arbitrariness of the system that gives the man’s performance its false authority. What we learn is not what empathy is, but what kinds of knowing are excluded when education becomes synonymous with performance.

Rancière’s politics of education resists the presumption of pedagogical hierarchy. Where traditional models assume a gap between those who know and those who do not, Rancière insists on the radical equality of intelligence. This is the guiding claim of The Ignorant Schoolmaster: that the teacher’s role is not to explain, but to affirm the student’s capacity to think. The woman in the cartoon embodies this refusal of hierarchy. She does not correct, educate, or respond within the man’s frame. Her silence is not the silence of submission, but of emancipated non-participation. She withdraws not from the scene itself, but from the script it presumes to follow. In this sense, the cartoon is not only aligned with The Ignorant Schoolmaster—it enacts its method. It offers no exposition, no correction, no didactic clarity. It simply stages a contradiction, and asks us to think. Like Jacotot’s emancipated pedagogy, it trusts that the viewer can discern what the scene refuses to say outright. The joke does not teach; it interrupts. And in that interruption, it models a form of learning that requires no master, only the willingness to stay with the failure of sense.

5. Humor as Epistemic Exposure

The cartoon, then, does not explain—it stages. It withholds precisely the kind of closure that the man demands, and in doing so, makes space for something else: not a lesson, but a rupture. In this, it aligns with the pedagogy of the ignorant schoolmaster—not because it offers equality as its content, but because it assumes equality as its form. It leaves the viewer to make sense of the failure, to dwell in the discomfort, to feel the weight of an epistemology unraveling in real time. It does not attempt to quantify confusion, resolve ambiguity, or scaffold insight into a rubric. It does not present learning as something to be tracked, but as something that happens in the break—in the moment where the given structure of knowledge ceases to hold.

The cartoon’s use of irony is central to this break. Irony, by its nature, marks a disjuncture between appearance and reality, between what is said and what is known. Here, that disjuncture is not a stylistic flourish—it is an epistemic operation. As Simon Critchley suggests, irony opens a space in which finite claims to knowledge reveal their inadequacy before the real. The cartoon’s irony does not resolve the contradiction it stages—it performs it, and in doing so, displaces the burden of resolution onto the viewer. Irony, in this sense, is not merely rhetorical—it is epistemological. It does not just say “this is funny”; it reveals that something does not add up. As Critchley notes, irony operates in the space between what is said and what is meant, between the surface of a statement and the world it fails to grasp. But when irony is enacted at the structural level—as it is in this cartoon—it exposes not a misstatement, but a misfit between the system and the real.

This is the deeper function of irony in the context of platform epistemology: it renders visible the assumptions that underpin the system by showing where those assumptions collapse. The man’s declaration—“I am empathetic; I watched the videos twice”—is structurally sound within the logic of content completion. But the cartoon’s irony makes us feel the dissonance between that logic and the world it purports to understand. In doing so, it reveals the system’s limits not as error, but as condition. Irony becomes a mode of knowing—a diagnostic operation that uncovers the disjunction between what can be claimed and what can be known. What irony teaches is not that the man is wrong, but that the epistemology in which he is right is itself absurd. And in this, irony does not offer correction—it offers exposure. It opens a space in which the viewer can see the system seeing itself fail.

Crucially, viewed as an educational experience, the cartoon does not ask for a response. It does not require recognition, agreement, or interpretation. It leaves the space of response radically open. And this may be its most pedagogically powerful move: by refusing to quantify or manage its reception, it makes room for response to emerge unpredictably—not as feedback, but as thought. In this way, the cartoon resists the very logic it depicts: it does not perform legibility; it invites understanding. This laughter is not cruel. It is not the laughter of superiority, as Bergson might suggest, nor is it a simple release. It is something closer to what Simon Critchley describes: laughter as lucidity. The cartoon does not make us laugh at the man—it makes us laugh at the system that has made his reasoning plausible, even familiar. The joke works not by mocking deviation, but by illuminating the normative absurdity of a system that equates watching with knowing, repetition with care, citation with relation.

This refusal to solicit or direct response is not simply an aesthetic restraint—it constitutes an ethics of reception. In a pedagogical landscape dominated by feedback loops, outcome tracking, and prescribed engagement, the cartoon does something quietly radical: it trusts the viewer to think. It assumes no need to monitor understanding, measure insight, or preempt interpretation. In this way, it models what Jacques Rancière calls a presumption of equality—not just between teacher and student, but between text and reader, form and witness. This is also what Gert Biesta refers to as the subjectifying dimension of education: not the delivery of content, nor the shaping of behavior, but the creation of space in which a subject can emerge in response to the world. The cartoon does not present knowledge to be acquired, nor does it shape the viewer according to a predefined outcome. Instead, it invites the viewer into a moment of non-closure, of disorientation that may or may not give rise to understanding—but that, crucially, respects the viewer’s freedom to respond, or not.

This is a pedagogical ethics rooted in restraint: the refusal to reduce ambiguity, to demand clarity, or to instrumentalize response. It grants the viewer space to feel uncertain, to remain unresolved, even to misunderstand. But that openness is not abandonment—it is an invitation. It allows for the possibility of thought that is self-directed, unscaffolded, and uncounted. It would be easy to object that we are attributing too much to the cartoon—reading into it a pedagogical intentionality or ethical restraint that may not have been intended. But the point is not that the cartoon seeks to model an alternative pedagogy. It is that its form performs one, however inadvertently. The cartoon does not ask for measurable understanding, not because it rejects platform metrics explicitly, but because its structure does not support them. It does not solicit reflection in quantifiable terms. It withholds the very scaffolding that would turn recognition into evidence.

In doing so, it creates the conditions for a kind of learning that exceeds platform logic—not because it replaces one lesson with another, but because it disorients the viewer just enough to make learning possible. The pedagogical potential lies not in the cartoon’s message, but in the non-closure it stages, and in the space that opens when no outcome is required. Where platform logic defines understanding by its legibility to the system, this cartoon stages an alternative: learning that begins not in recognition, but in disorientation. And the ethical gesture lies in letting that disorientation remain—unmeasured, unclosed, unclaimed.

6. Gendered Knowledge and Rationalist Authority

The cartoon’s epistemological dynamics are not only pedagogical and affective—they are gendered. The man’s certainty, his performance of competence, his belief in completion as proof of capacity—these are not merely personality traits. They are expressions of a broader rationalist tradition, one that codes knowledge as accumulation, understanding as demonstrability, and learning as mastery. These are not neutral logics. They are masculinized logics, shaped by a long epistemological history in which authority, clarity, and control have been culturally aligned with masculinity. Feminist theorists such as Sandra Harding, Donna Haraway, and Evelyn Fox Keller have long critiqued this tradition. They have shown how dominant epistemologies routinely exclude, devalue, or erase affective, situated, and relational modes of knowing. Harding calls for “strong objectivity”—a standpoint that acknowledges the partial, located nature of all knowledge. Haraway warns against the “god trick” of seeing everything from nowhere. And Keller explores how the culture of science has privileged detachment over connection, abstraction over relation.

In this light, the cartoon’s logic begins to take on a distinctly gendered shape. The man’s confidence in his repetition of content as proof of empathy is not just a cognitive error—it is a performance of epistemic legibility within a masculinized system. He asserts understanding in the only terms that the system will recognize: completion, quantification, citation. He is fluent in the language of metrics, and so he appears as a competent knower—even as the cartoon exposes the hollowness of that fluency. The woman, by contrast, is rendered epistemologically illegible. She is not validated by the system, nor does she perform in ways that the system can register. Her silence is not just non-compliance—it is excess, a form of knowing that exceeds the rationalist framework entirely. She does not offer data. She does not scaffold feedback. She does not render herself available to measurement. In the logic of the corporate-tech-ed-complex, she does not count—literally.

And yet, her presence haunts the scene. She is the measure by which the man’s performance is revealed as inadequate. She is the horizon that exposes the failure of completion to produce relation. In this way, she embodies what Haraway might call a different figurability: not a clearer or more articulate knowledge, but a knowledge that refuses to separate itself from the body, the moment, the relation. The cartoon, then, is not only a critique of pedagogical structure—it is a gendered exposure of how epistemic authority is performed, recognized, and withheld. It shows us that what is seen as “knowing” is not only shaped by form and platform, but by gendered histories of recognition—histories in which the relational, the affective, and the tacit have been marked as secondary, feminine, or irrelevant.

The cartoon, then, is not only a critique of pedagogical structure—it is a gendered exposure of how epistemic authority is performed, recognized, and withheld. It shows us that what is seen as “knowing” is not only shaped by form and platform, but by gendered histories of recognition—histories in which the relational, the affective, and the tacit have been marked as secondary, feminine, or irrelevant. More broadly, the cartoon reveals how identity itself functions as a condition of legibility within this epistemology. It is not just that some subjects are underrepresented or underserved—it is that the epistemic terms of inclusion are already prefigured by the system’s logic. To be recognized as a knower, one must perform knowledge in the system’s preferred mode: visible, assertive, quantifiable. Those who do not—or cannot—perform in this way are not merely excluded; they are constituted as epistemically excessive, or even unintelligible.

This moves us beyond normative frameworks of inclusivity, which too often reduce difference to a problem of access or representation—what Rinaldo Walcott and others have described as “malrecognition.” In such frameworks, marginalized identities are invited into systems of knowledge only on predefined terms: terms that require them to translate their ways of knowing into dominant forms of legibility. The result is not epistemic justice, but epistemic assimilation, where inclusion becomes a form of containment. This critique is central to feminist epistemology. Sandra Harding has long emphasized that knowledge systems are never neutral—they reflect social structures and power relations, including those tied to gender, race, and class. Donna Haraway’s insistence on situated knowledges challenges the myth of epistemic universality by foregrounding partiality and embodiment as conditions of all knowing. Gayatri Spivak, too, reminds us that when the subaltern speaks in a voice unintelligible to dominant discourse, she is often not heard at all. The question, then, is not simply who gets to speak, but who gets to appear as a speaking subject within a given epistemology.

This is particularly evident in the discourse of accessibility within EdTech, which is often framed as a technical solution—ensuring that more users can interface with standardized content. But as Sara Ahmed has shown, institutional commitments to diversity and access frequently operate by smoothing over the very structures that produce exclusion. Accessibility, in this mode, becomes about enabling broader participation in the dominant epistemology, rather than challenging the forms of knowledge and performance that define it.

And so, we find ourselves in a closed loop: expanding access not to different ways of knowing, but to the same structures of visibility, the same metrics of completion, the same forms of epistemic legibility. As José Medina argues in his work on epistemic injustice, the problem is not just epistemic exclusion, but the foreclosure of epistemic possibility—the closing off of alternative ways of seeing, feeling, and relating to knowledge. To be included, then, is to be made legible—not on one’s own terms, but on the system’s. And so the deeper epistemic violence remains: not just in who is seen, but in what kinds of knowing are allowed to appear as knowledge at all.

7. The Table as Pedagogical Theatre

Up to this point, we’ve traced how the cartoon stages failures of epistemology: how its irony exposes the limits of quantifiable learning, how its form resists closure, and how it reveals the gendered and structural exclusions of dominant knowledge systems. But these failures are not abstract. They are spatially and socially situated—rendered through a specific setting, with specific bodies, under specific expectations. The cartoon takes place at a table. A date. A setting that should call forth relational presence, mutual curiosity, and affective attunement. Instead, it becomes a site of performance, a scene of misalignment, an encounter where the pressures of legibility override the possibility of connection.

This table—so ordinary, so familiar—quietly metaphorizes the conversion of everyday life into a platformed learning environment. It is here that the broader dynamics of the corporate-tech-ed-complex are brought down to human scale. And in this scene, we begin to see how educational logics bleed into interpersonal domains—not only shaping how we perform knowledge, but how we fail to meet one another. The table at the center of the cartoon is more than a piece of furniture. It is a stage. A scene of interaction, evaluation, performance. What appears to be a date—a casual, social, even romantic setting—is in fact rendered as something else entirely: a site of unsanctioned pedagogical assessment. The man performs his credentials. The woman bears silent witness. The cartoon captures not a conversation, but a test—the failed demonstration of a competency, carried out under the unspoken pressure to appear emotionally qualified.

In this way, the table becomes a kind of pedagogical theatre, a compressed space in which the broader logics of platform education are transferred into the interpersonal realm. The man behaves as though he is being scored, or worse, that he must assert authority in order to be evaluated favorably. What should be a scene of mutual attunement becomes a scene of epistemic anxiety. He must prove that he understands empathy, rather than simply being empathetic. Presence gives way to performance. This is not incidental. It is a parody of platform logic, where the success of relationality is measured not by mutual responsiveness, but by demonstrable fluency in pre-determined competencies. Under this logic, the man does not read the room; he performs for it. He does not engage the other; he cites his engagement credentials. The table, then, is not neutral—it is shaped by the same cultural forces that shape the user interface. It flattens the conditions of relational being into a point-of-interaction design, optimized for proof, not presence.

This theatrical staging is reinforced by the cartoon’s visual composition. The two characters are symmetrically placed, divided by the small round table—a classic image of formal dialogue. But the balance is deceptive. The man leans forward, gesturing with one arm, mouth open in declaration. His posture signals assertion, effort, projection. The woman, by contrast, remains reclined, arm drawn in, body language closed. She offers no outward gesture, no mirrored energy. The asymmetry of posture stages the asymmetry of epistemic demand: he is performing for recognition; she withholds the frame through which that recognition would be granted. The physical space between them is narrow, but the epistemic distance is vast—and deliberately maintained.

Even the cartoon’s visual style reinforces this epistemic configuration. Its flat, minimal composition—clean lines, centered framing, symmetrical balance—does more than simplify: it performs the disembodiment of cognition. This is a world rendered in Cartesian space, where bodies are reduced to vectors of expression and where learning, like thought, is imagined to occur nowhere and everywhere at once: abstract, modular, decontextualized. The absence of visual texture or depth mirrors the presumed neutrality of platform epistemology, in which cognition is stripped of affect, context, and materiality. And yet, this very flatness becomes a form of critique. By embodying the aesthetics of disembodied learning, the cartoon shows us what gets lost: relation, opacity, presence. Its refusal of depth is not a failure of form but a parody of the very cognitive minimalism it stages.

What the cartoon stages, then, is not simply a failed date, but the absurdity of UI/UX logics imported into social life. This is the world imagined by the corporate-tech-ed-complex: one in which every interaction is a site of feedback, every relationship a space for optimization, and every performance a form of data. It is a world where “being good at empathy” means being able to show that one has completed empathy-related content, and where “learning” becomes indistinguishable from behavioral rehearsal. And yet, the cartoon resists that logic through form. It refuses to clarify, correct, or optimize. It gives us only the failed scene, unscaffolded. And in doing so, it calls attention to what has gone missing: the relational immediacy that no metric can capture, no content module can substitute, and no table—however well-designed—can restore once the space of mutual presence has been converted into a performance zone.

9. The Scene as Microcosm of Platform Governance

If the man in the cartoon has misread the situation, it is because the platform has already trained him to do so. What unfolds at the table is not simply a failure of social attunement—it is the success of a system that governs through internalized feedback loops. The man does not perform for the woman across from him; he performs for the invisible logic of assessment that has colonized his relational reflexes. This is not a dialogue. It is an examination, in Foucault’s sense: a moment in which the subject is compelled to display their alignment with institutional norms. The man’s declaration—“I’ve watched every Khan Academy video on human emotion. Twice.”—is not addressed to the woman so much as to the system that has taught him what counts as empathy. He does not respond to her presence. He responds to the metrics that have pre-shaped the scene of encounter. And in this sense, we might also understand his gesture as a form of interpellation in Althusser’s terms: the moment a subject is “hailed” by a system and takes up the position it offers. The man believes he has been called to perform a certain kind of legibility—and he answers with citation, not presence. He performs empathy as compliance.

But, as Judith Butler reminds us, interpellation is never seamless. To cite an identity or a competency is to perform it within a context that may accept or reject it. Here, the citation fails. The situation demands relation, not repetition. And yet the man cannot access the relational because he has been trained to anticipate evaluation. He mistakes a moment of presence for a moment of proof.

This is how platform governance operates—not by coercion, but by habituation. Its metrics, modules, and feedback tools do not simply track behavior; they reformat subjectivity, producing individuals whose primary orientation is toward performance and compatibility. The man has not misunderstood empathy; he has embodied the system’s definition of it. He has been shaped not for relation, but for submission to legible protocols. And when the frame shifts, he cannot follow.

The brilliance of the cartoon is that it stages this logic without any overt mechanism of control. There is no interface, no data visualization, no instructional overlay. And yet the platform is everywhere. It governs the man’s affect, his posture, his speech. The table becomes a miniaturized platform environment, in which the rules of feedback and recognition have been so deeply internalized that they structure even the most intimate forms of encounter. The cartoon stages not a failure of understanding, but a subject successfully overfitted to the wrong world. And so the man’s absurdity is double. On the surface, it lies in his overfitted submission to platform logic—his attempt to navigate an intimate, affective encounter as if it were a competency-based learning module. But at a deeper level, it exposes the ideological absurdity of education itself—not just under EdTech, but as a long-standing structure of credentialism, behaviorist performance, and ritualized demonstration. What the cartoon lampoons is not just the man, but the entire system that taught him to think this was learning.

In this sense, the cartoon stages a deeper irony: its punchline lands only because we already know that this kind of learning doesn’t work. We laugh because the ritual has already been hollowed out in our collective awareness. The value of education has been displaced onto its signs—course completions, scores, certificates—not because we believe in them, but because we know that others will. These markers retain social exchange value, even when they no longer signify transformative learning—except, perhaps, the capacity to navigate the system that demands them. This is ideology in Žižek’s sense: not belief in something true, but the continued performance of belief in something we know to be false.

But the man in the cartoon is something else. He does not exhibit the ironic distance that Žižek identifies as typical of contemporary ideology—that gesture of “I know this is nonsense, but…” Instead, his belief is total. He is not performing compliance with a system he sees through; he is sincerely immersed in its logic. His belief is not Žižekian ideology—it is a kind of retrograde false consciousness, an uncritical fidelity to the surface codes of education-as-certification. He does not believe despite knowing it’s false; he believes because he does not know it’s false. And this sincerity is precisely what makes him absurd. This is why he appears not just as a misfit, but as a comic type—a Homer Simpson, a Spinal Tap guitarist, a regional manager in The Office. His complete identification with managerial rationality, with the form of learning as deliverable, legible, and certifiable, is what the cartoon renders laughable. And yet, the irony runs deeper still. For those of us who laugh—who see ourselves as somehow outside this logic because we are aware of its absurdity—the cartoon implicates us too. Žižek reminds us that irony is not freedom from ideology; it is often the very mode by which ideology sustains itself. We laugh not because we are free of belief, but because we manage the dissonance of believing in what we know isn’t real. Irony becomes a kind of affective airlock, allowing us to maintain the illusion of critical distance while still participating in the system’s rituals.

In this light, the cartoon is haunted not only by the man’s failure to recognize irony, but by the irony of our own recognition—a recognition that does not liberate us, but reveals how thoroughly we’ve internalized the very logic we presume to critique. The managerial rationality that produced him is the same one that conditions our understanding of what counts as knowledge, effort, success—even critique itself.This brings us back to the ritual structure of education itself—a system we participate in not because we believe in its transformative capacity, but because we know it functions as a socially recognized form of exchange. The man in the cartoon may be an extreme case, but his logic mirrors a broader truth: education retains its force not through intrinsic learning, but through its institutional credibility. This is, after all, what a credential is—a document not of transformation, but of credibility, from the same Latin root as credo: to believe, to trust (as in credit, creed, credibility). A credential signals not what one knows, but that one has been seen to have known in the right place, in the right form, in a manner that is socially sustained, even if known to be arbitrary. And in this sense, education functions as cultural currency, a mechanism for social and economic legibility, regardless of whether learning has occurred. And this is currency in a very real sense, both in by transforming "learning" reified as purchasable commodity, and as currency in a job market.

This is why the proliferation of micro-credentials, badges, and certifications on platforms like LinkedIn feels both absurd and inevitable. These are not signs of learning; they are signs of visibility, indexed to a system in which knowledge is no longer valued for its content but for its commodifiability. Learning becomes something to display, not something to undergo. The platform does not invent this logic; it accelerates and scales it. What was once confined to schools and universities is now fully integrated into the attention economy—packaged, gamified, and monetized. In this light, the man in the cartoon is not outdated. He is early. And it is currency in the most literal sense—both as learning reified into purchasable, displayable commodity, and as market value in professional economies. What matters is not transformation, but transaction. Not meaning, but mobility. The platform did not invent this logic; it simply streamlined, digitized, and scaled it. The man in the cartoon does not misunderstand education. He performs it—perfectly.

But in doing so, he also reveals the auto-deconstructive nature of the credential itself. As a sign of learning, the credential is designed to confer legibility. And yet, it foregrounds the arbitrariness of its own mark—that learning has been validated not by change, understanding, or relational encounter, but by having passed through the right format, at the right time, according to the right rubric. The credential persists as both evidence and erasure: a sign of education that quietly undoes the very conditions under which learning might still be possible. This is precisely what the man’s utterance of “twice” enacts. It is both a claim to distinction and a sign of insufficiency—a repetition that is meant to prove learning, but instead exposes its absence. “Twice” functions as a micro-credential, a personal badge of effort that dramatizes the larger logic of the platform: repetition becomes remedy, accumulation becomes expertise, and belief becomes performance. In uttering it, the man reaffirms the system while also unwittingly revealing its collapse. The credential, like the cartoon itself, means more than it can contain—and in that excess, the system stutters, even as it persists.

10. Conclusion: Pedagogy by Cartoon

What we’ve traced so far is not simply a satire of an awkward exchange, but a diagnostic exposure of the conditions that make such an exchange possible—and plausible. Through irony, spatial staging, silence, posture, and performance, the cartoon enacts a critique of a much broader system: one in which knowledge is rendered as demonstrable, quantifiable, and legible, while relational, embodied, and affective forms of understanding are rendered as noise, excess, or absence. This is a pedagogy not of emergence, but of containment—one that resists rupture, smooths unpredictability, and funnels all experience into predefined learning paths where even the language of inclusivity or personalization is constrained by pre-approved outcomes.

Across these scenes, we have seen how platform logic not only structures cognition, but deconstructs itself: a system defined by the imperative to educate, yet built on epistemic processes—metrics, assessments, performative demonstration—that preclude the very conditions under which education can occur. The result is an architecture designed for scale, built on a model of learning that privileges disembodied rationality, demonstrable competence, and hierarchical legibility. Even its gestures toward equity become modes of standardization. The platform presumes to deliver education while evacuating the friction that makes learning transformative.

This logic is not neutral. It extends from—and preserves—the historical epistemology of the humanist subject: rational, self-possessed, white, Western, and male. Those who do not conform to this figure are not simply left out; they are rendered epistemologically illegible. The woman in the cartoon is not misunderstood—she is unrecognized by the very terms of the exchange. Her silence, her refusal to perform legibility, makes visible what the system cannot admit: that what it names as “learning” is already structured by exclusions so deep they appear natural.

And yet, through this critique, we have also traced the contours of an alternative pedagogy—one that the cartoon performs, quietly, structurally, and affectively. It does not name itself. It does not correct. It does not explain. But through its irony, its asymmetries, its silences, it models another kind of learning: one rooted in rupture, in withheld closure, in the refusal to scaffold interpretation. Like the woman within the frame, the cartoon withholds legibility and speaks through its silence. It does not assert a new pedagogy; it enacts one—a pedagogy of friction, irony, and epistemic interruption. And in doing so, it provides a space not for recognition, but for response—unmeasured, uncounted, and yet unmistakably pedagogical.

That a single-panel cartoon can serve as evidence in a philosophical and epistemological critique is not a failure of rigor—it is a recognition of what constitutes cultural knowledge. The cartoon’s humor only works because its premise already circulates within a shared epistemic framework. It is intelligible not in spite of its absurdity, but because of it. The man’s declaration—“I’ve watched every Khan Academy video on human emotion. Twice.”—is funny only because we already understand its logic: the substitution of repetition for transformation, of citation for relation, of platform compliance for emotional intelligence. The cartoon is not just about this world; it is of it. Its critique is made possible by the very epistemology it lampoons. In this way, it becomes an artifact of empirical epistemology: evidence of a worldview that is so widely naturalized that even its breakdown reads as comic rather than catastrophic.

I call this worldview the techno-educational corporate complex—a system in which learning is no longer defined by emergence, relation, or transformation, but by managerial rationality, technological mediation, and platform legibility. It is a system that did not begin with technology, but has been accelerated and scaled by it. The complex operates not only through institutions but through forms of knowing: it redefines what counts as learning, who counts as a learner, and what forms of knowledge are allowed to appear.

The cartoon stages this complex through a compressed scene of epistemic failure. It articulates its logic through the man’s posture, speech, timing, repetition, and the woman’s silence. In that staging, we encounter the complex’s interdependent features: the optimization logic of managerial rationality; the UI/UX design constraints that shape pedagogical form; the instructivist epistemology that treats knowledge as modular and deliverable; the instrumentalism that values learning only for its market use; the shift from cognition to performance; the closure of learning through automated feedback loops; the structural contradiction of a system that simulates transformation while foreclosing it; the demand for epistemic legibility that excludes other ways of knowing; and the internalization of platform governance that reshapes subjectivity itself. Even the man’s final gesture—“twice”—functions as a self-deconstructing credential, a micro-badge of sincerity that reveals the hollowness of the very system it tries to affirm.

And yet, in this failure, something else flickers into view. The cartoon does not explain. It stages. It withholds. It disrupts. It offers no lesson, but in doing so, it enacts a form of learning otherwise. It does what the video did not. It invites dissonance, recognition, even refusal. In this way, it performs a counter-pedagogy: one that does not presume mastery, but makes room for the rupture that education, at its best, has always required. If the techno-educational corporate complex trains us to perform knowing, the cartoon quietly invites us to feel what has been forgotten. And in that feeling, something like pedagogy begins.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.” In Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, translated by Ben Brewster, 127–86. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971.

Andrejevic, Mark. Automated Media. New York: Routledge, 2020.

Biesta, Gert. Beyond Learning: Democratic Education for a Human Future. Boulder: Paradigm, 2006.

Butler, Judith. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Cottingham, Rob. “Emotional Distance Education.” Noise to Signal, July 11, 2012. https://www.robcottingham.ca/cartoon/archive/emotional-distance-education/

Crary, Jonathan. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. London: Verso, 2013.

Simon Critchley, Very Little… Almost Nothing: Death, Philosophy, Literature (London: Routledge, 1997).

Critchley, Simon. On Humour. London: Routledge, 2002.

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Dewey, John. Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan, 1938.

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2009.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–99.

Harding, Sandra. Whose Science? Whose Knowledge?: Thinking from Women’s Lives. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Illouz, Eva. Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007.

Keller, Evelyn Fox. Reflections on Gender and Science. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Medina, José. The Epistemology of Resistance: Gender and Racial Oppression, Epistemic Injustice, and the Social Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Rancière, Jacques. The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation. Translated by Kristin Ross. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 271–313. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso, 1989.