Floating Through the Fire: Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book and the Sound of Unspoken Struggle

Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book is an album that floats. Not in the sense of detachment or drift, but in its refusal to be pinned down by the gravity of any single genre, sentiment, or social demand. Released in 1972—between the marches and the aftermath, in the tension between civil rights and personal renaissance—it neither preaches nor pleads. Instead, it hovers in the liminal space between joy and mourning, groove and grief. There is something untethered about it, as if Wonder had found a way to make beauty while slipping just beyond the grasp of the world’s pain. And yet the album is permeated by that pain—haunting, unresolved, refracted through the lens of desire, defiance, and sonic experimentation. Talking Book doesn’t describe a world in struggle; it emerges from one, with all the clarity and ambiguity that implies.

I feel like this is the beginning… And already we’re adrift. Already we’re late. Already we’re somewhere we didn’t expect to be. There’s joy, yes. But not without its shadow. The album lifts you, solemnly. Carries you across something hot and unspoken. This isn’t a protest record in the familiar sense. But struggle permeates it—not in content, but in condition. The tones are soaked in it. The progressions strain against it. The silences echo with it. There are no signs that say you are here. There is only movement. Only sound. And somehow, Stevie Wonder makes that sound into a world.

The Edge of Sentiment: Listening for the Turn

If Talking Book begins with love, it doesn’t stay there. Or rather, it doesn’t stay in the safe version of love. “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” seems, at first, like a wedding song. But even in that opener, there’s unease folded into the joy: “If I thought our love was ending / I’d find myself drowning in my own tears.” That’s not a clean romantic image—it’s a line soaked in vulnerability and terror. This isn’t love as fulfillment; it’s love as condition, fragile and omnipresent, already haunted by its possible loss. The album starts with warmth, but it’s the warmth of a low sun casting long shadows.

And that’s the move Wonder keeps making—again and again. He pulls us to the verge of sentimentality, to the point where the feeling should break into cliché—but then he steps sideways. There’s a sleight of hand, or maybe a sleight of heart. The tones shift. The lyrics sharpen. The groove lurches or dissolves. We find ourselves just past the edge of the familiar, drawn into a deeper layer of emotional and sonic ambiguity.

Take “You and I (We Can Conquer the World).” It should be a triumphant declaration. But listen closely—his delivery isn’t triumphant. It’s hesitant, slow, almost funereal. There’s a strange gravity to it, like the song already knows the world won’t be conquered, not really, but that saying so is still an act of devotion. Or consider “Blame It on the Sun.” The very title reframes heartache as cosmology. He’s not just sad—he’s disoriented, planetary, cosmically out of sync. It’s absurd in the way deep grief often is: casting about for something big enough to hold the feeling, then settling on the sun, because what else is there?

This is not the genre of saying how you feel. It’s the genre of feeling as genre, where even funk loses its confidence and slips into something unnameable–a kind of funk expressionism that exceeds form. Wonder bends the form not to show off technical mastery (though it’s all there), but to stretch the emotional palette past the limits of coherence. The clavinet doesn’t groove so much as speak in tongues on “Maybe Your Baby.” The song’s structure unravels, mutates. Funk becomes menace, desire becomes threat.

The refusal of sentimentality isn’t a coldness—it’s a commitment to staying with complexity. Talking Book doesn’t offer love songs, it offers devotionals etched in uncertainty, intimacy, futurity, and the quiet knowledge that any feeling worth holding will one day exceed its name.

Circuitry and Spirit: Technology as Soul in Talking Book

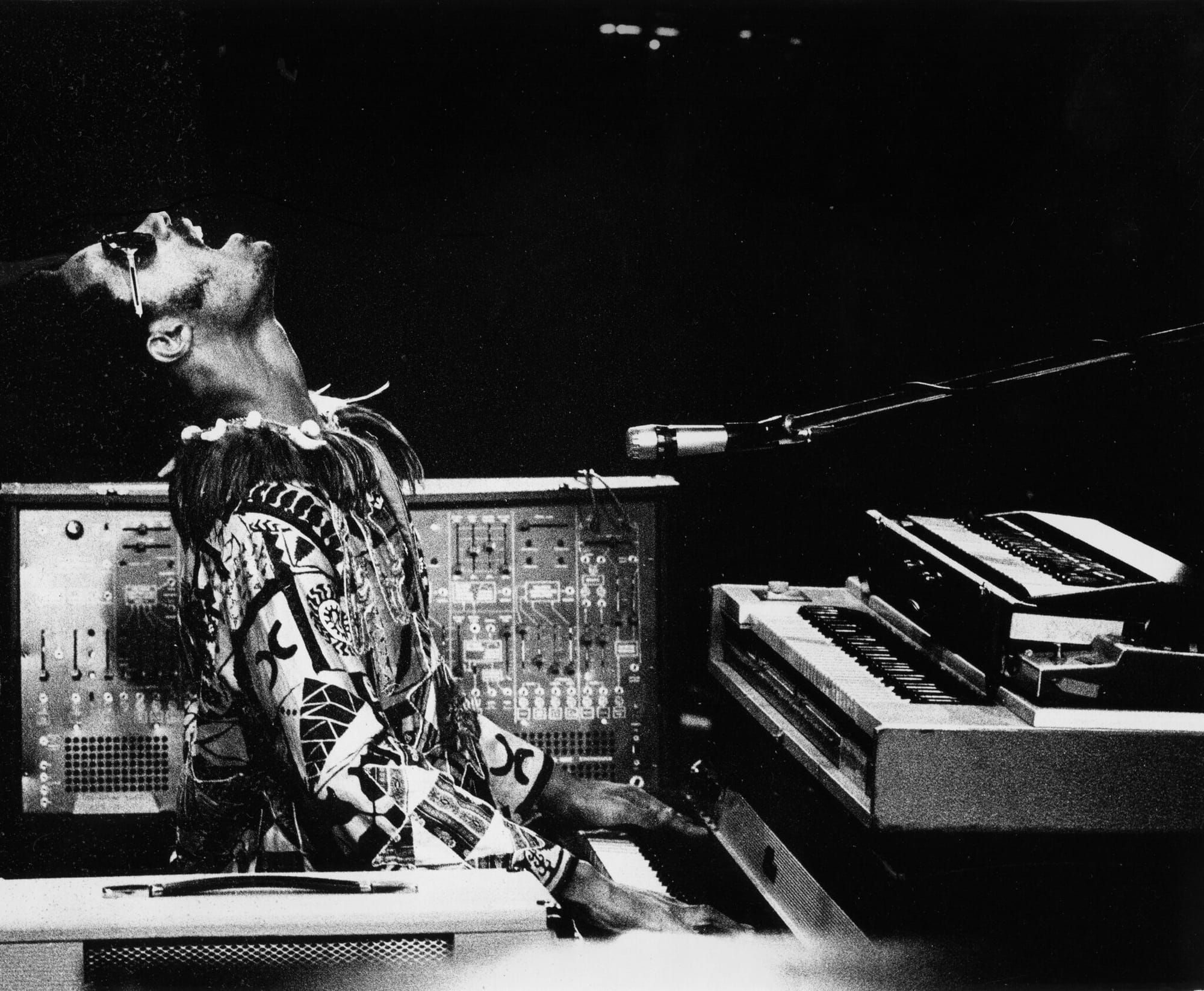

The great trick of Talking Book is that it sounds human—achingly, intimately human—while being deeply, unmistakably synthetic. This is not a contradiction for Stevie Wonder. In his hands, the Moog synthesizer doesn’t sound like the future; it sounds like feeling. The Hohner clavinet doesn’t mimic a guitar; it sweats. The machines don’t pretend to be real—they become real through affect. Wonder doesn’t use technology to simulate the human voice; he uses it to extend it, to multiply it, to let it leak out sideways.

“Maybe Your Baby” is a case in point. The fuzzed-out clavinet doesn’t follow the rhythm so much as challenge it—dragging against the beat, sticking to the corners of the groove. It’s funky, yes, but not in the clean, affirming sense. It’s nasty. It snarls. The synth becomes a proxy for all the things Wonder’s voice won’t quite say. It sounds like betrayal, jealousy, rage—but also like sex, confusion, detachment. He’s talking about loss, but he’s grooving through it, and the groove refuses closure. The result is a sound that’s haunted and compulsive: you move to it, but you don’t feel better. You feel compelled.

Then there’s “Superstition”—a song built around that now-iconic clavinet riff. On its surface, it’s a warning about belief and irrationality. But sonically, it’s hypnotic. The clavinet isn’t just catchy; it’s incantatory. It loops and loops, winding around itself like a spell. Wonder’s voice floats on top, teasing clarity, but the beat underneath keeps tightening. The song becomes a contradiction: funk as control and funk as chaos. It works because it doesn’t resolve the tension—it embodies it.

And here’s the deeper move: by refusing to hide the synthetic elements, Wonder reorients soul music away from authenticity as naturalness and toward authenticity as effect. He doesn’t need the grain of the voice to prove his humanity. He builds an entire emotional infrastructure out of circuitry. He doesn’t add feeling to the machine; he finds feeling in the machine.

This is why the album feels so personal yet so untethered. It’s not grounded in realism—it’s grounded in sensation. Wonder’s use of tech is spiritual, not just sonic. The instruments are his choir, his ghosts, his second self. There’s a long tradition in Black music of making technology breathe—from Sun Ra’s Afrofuturist keyboards to J Dilla’s off-kilter drum machines—and Talking Book stands as a bridge in that lineage. Wonder’s synths don’t represent escape from the real; they reveal the real as already mediated, already modulated, already vibrating with longing and resistance.

The Sonic Procession: Ecstasy, Color, and the Collapse of Boundaries

To call Talking Book a spiritual journey is accurate—but only if we break open what we mean by “spiritual.” This is not the solemn asceticism of gospel. It’s not the structured uplift of moral clarity. It’s something wilder, looser. Talking Book is ecstatic in the old sense: to be outside oneself. It’s possessed—not by demons or doctrine, but by the full-spectrum charge of being alive in a body, a nation, a history, a groove.

This is why the album doesn’t feel like a sequence of songs. It feels like a sonic passage—a hybrid landscape full of pulsing color, feverish transitions, and emotional contradiction. It’s lush, almost surreal. The keyboard tones don’t sit quietly beneath the vocals—they shimmer, fracture, melt. His voice doesn’t hold steady; it slips, stretches, erupts. One moment you’re in a love song. The next, you’re caught in an ancestral vision of paranoia (“Superstition”), displacement (“Big Brother”), or quiet revolt. But it’s never declared. It just… seeps. That’s how Wonder lets struggle saturate the album—not by pointing to it, but by allowing no boundaries between love and fear, politics and eros, loneliness and prophecy.

The carnival here isn’t a party—it’s a refusal of categories. Songs bleed into one another not through production tricks, but through a kind of metaphysical weave. The characters shift: the I becomes we, the lover becomes a prophet, the broken man becomes a cosmic witness. Even time collapses. “I feel like this is the beginning / Though I’ve loved you for a million years.” Talking Book is always happening right now, even as it’s haunted by what came before and charged with what could come next.

And that’s why the civil rights struggle is present even when unspoken. Wonder doesn’t just sing about injustice—he sings within it, through it. “Big Brother” is the most explicit moment, yes, but even “Lookin for Another Pure Love” carries the ache of loss that feels larger than romance. There’s no need for slogans. The historical weight is in the tonality, the restraint, the release. Wonder doesn’t offer protest anthems; he offers conditions. The album is what it feels like to be inside a world structured by struggle but alive with imagination.

And so, Talking Book becomes something else: not a statement, but a space. A hybrid, ecstatic, embodied zone where joy is dissonant, grief is melodic, and technology hums with the resonance of lived Black futurity. It’s neither retreat nor anthem—it’s a wandering, colorful, overheated sermon with no pulpit, no altar, and no exit. Only passage.

Sounding Against the Moment: Resonance, Divergence, Legacy

You can feel Talking Book brushing against the soul currents of its time—Donny Hathaway, Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield—all navigating how to sing love and liberation in the same breath. But where Hathaway sanctifies pain and Gaye pleads for mercy, Stevie wanders. He doesn’t stay in the ache, and he doesn’t rise out of it either. He grooves through it, loops it, refracts it through synths and delay and tonal heat. Talking Book doesn’t ask for answers. It multiplies feeling until categories give out.

Compare it to What’s Going On—another masterpiece of that era. Marvin Gaye’s album builds a world of narrative coherence: a soldier comes home, sees the streets, prays, mourns, pleads for peace. It’s heartbreaking in its clarity. But Talking Book sidesteps that structure entirely. There’s no arc. No storyline. No “meaning.” Just a kind of embodied atmosphere of knowing. If What’s Going On is a plea for recognition, Talking Book is an act of being—saturated, unresolved, and more elusive for it.

Or think of Sly Stone—especially the crumbling brilliance of There’s a Riot Goin’ On. That’s an album full of distortion and sedation, rebellion turned inward. It’s brilliant, but bleak. Stevie, by contrast, doesn’t implode. He disperses. His funk doesn’t collapse—it swirls. There’s heat but not despair. The pain isn’t anesthetized; it’s transformed into groove. And while Sly mutters from the corner of the party, Stevie opens the door to a room that’s half dancefloor, half séance.

You can also hear the future humming in Talking Book. Prince will take its hybrid sensuality and spiritualism and crank it into erotic prophecy. D’Angelo will absorb its liquid textures and elusive structure and stretch them into soul’s third dimension. Even hip-hop—especially its more reflective edges, like André 3000, J Dilla, Kendrick—carries that same refusal of linearity, that same method of building truth through tone, not proclamation. Talking Book doesn’t assert authority. It invites you into a frequency.

And yet, for all its influence, it remains singular. It is not a turning point or a thesis. It’s a wavelength—not meant to be repeated, only caught. Stevie would go on to make more expansive albums (Innervisions, Songs in the Key of Life), but Talking Book remains the most intimate. Not smaller, just closer. Like someone humming next to your ear as the world turns strange and luminous.

The Freedom to Fracture: Wonder’s Break and the Birth of the Book

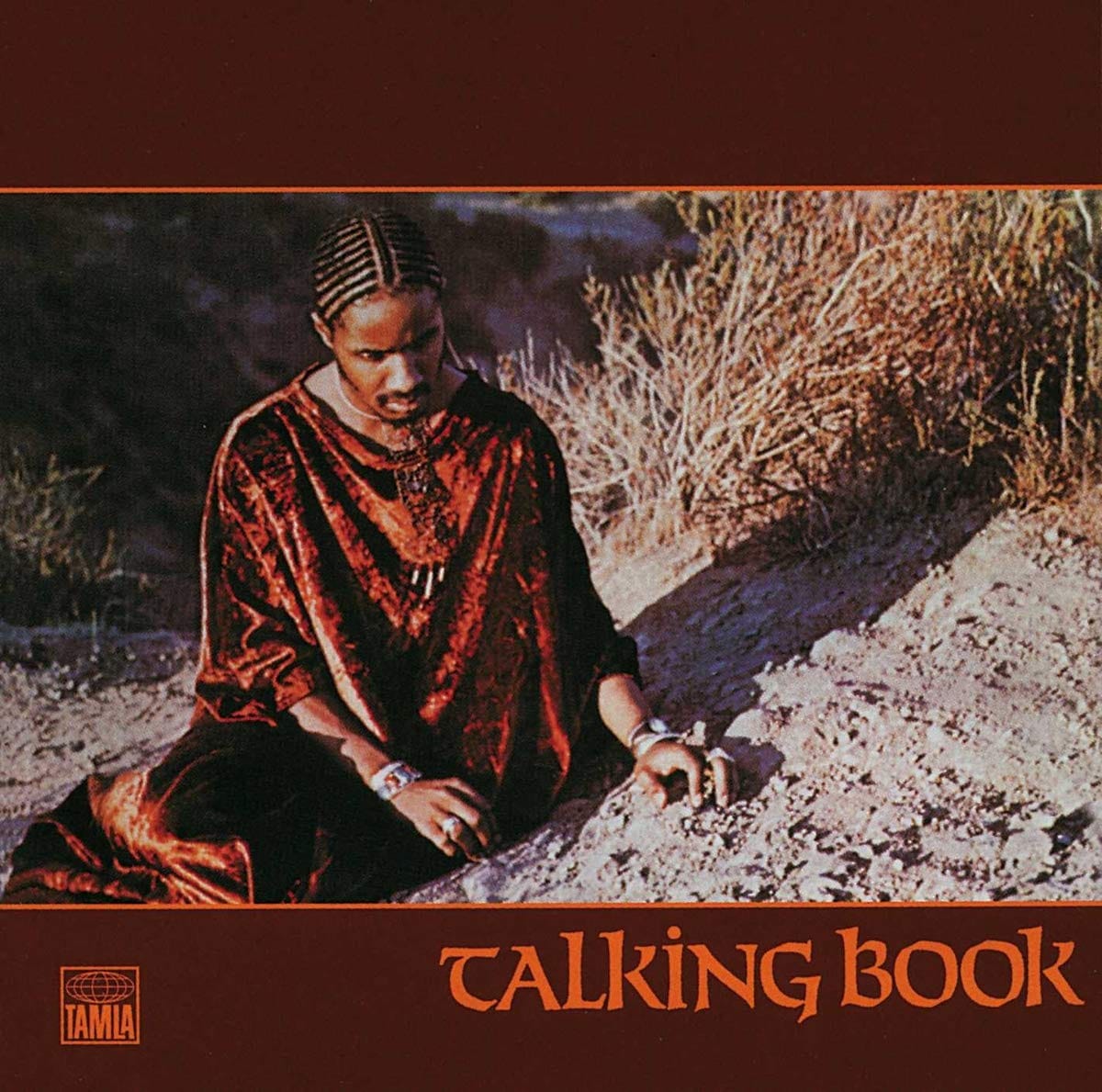

Talking Book doesn’t just sound like liberation. It is the sound of someone having finally won the right to speak in their own voice, on their own terms, with tools of their choosing. This wasn’t inevitable. Before this, Stevie Wonder was still considered “Little Stevie”—a prodigy, yes, but still channeled through Motown’s assembly-line polish. Singles. Hooks. Clean arrangements. There’s brilliance in that era, but there are boundaries too.

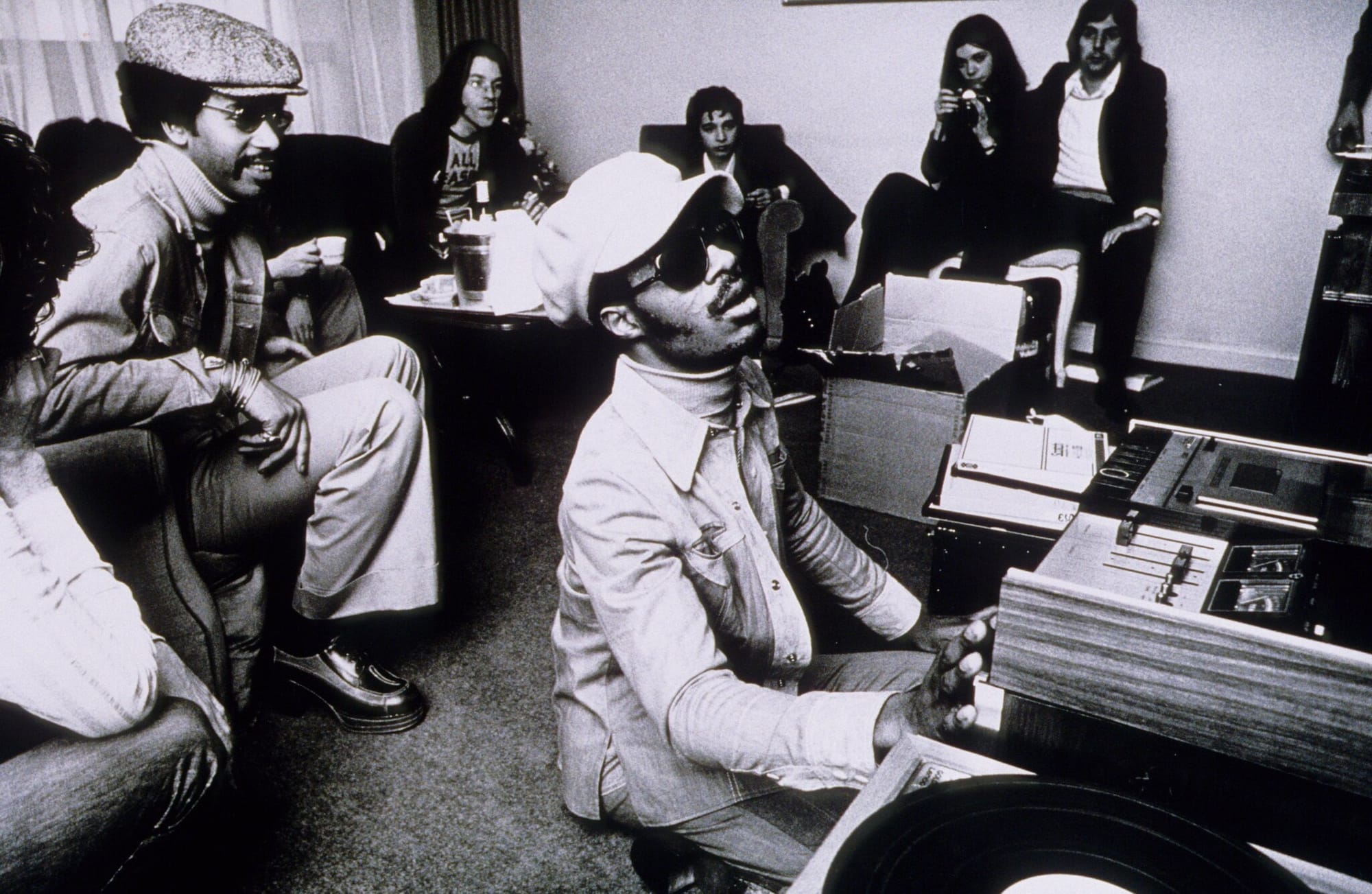

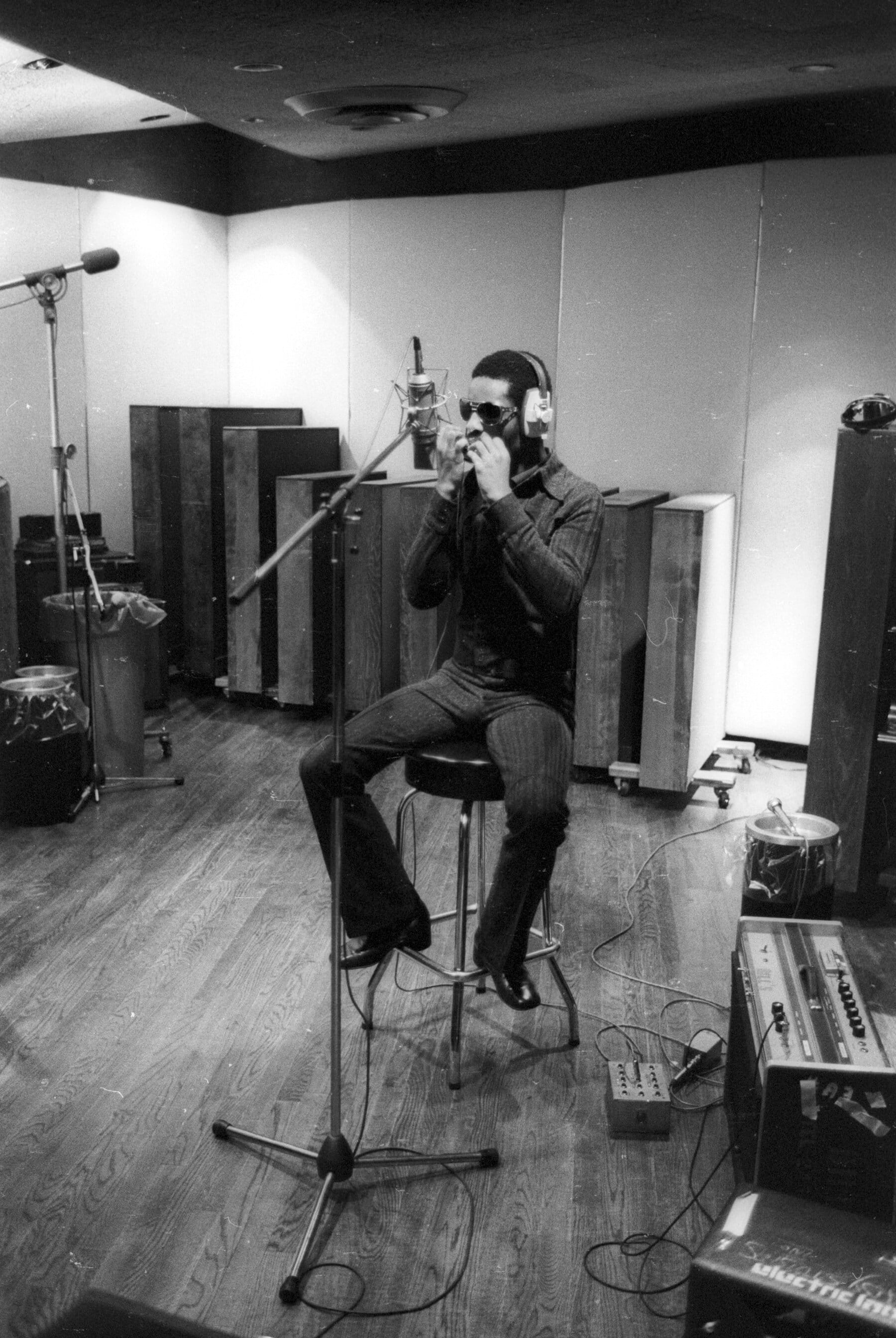

But Stevie turned 21, and with it came the renegotiation. He studied synthesizers. He linked up with Bob Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil, white sound engineers who treated analog synths not as novelty but as organisms. They weren’t just producers—they were co-conspirators in building a studio ecology where Wonder could become untranslatable. What resulted wasn’t just a change in tone or instrumentation. It was a total reformatting of musical authorship. The songs didn’t just carry his voice—they carried his will.

That’s part of what you hear in Talking Book—the intimacy of authorship. Stevie isn’t interpreting. He’s not fronting. He’s building. Every synth swell, every offbeat drum feel, every breathy vocal glide—he placed them. Even the mistakes feel intentional. The whole record breathes with the confidence of someone who has stepped outside the system that raised him and said: I know more than you think I do.

And this, maybe, is the quiet rupture: Stevie didn’t reject beauty. He bent it. Most artists, when given that kind of freedom, go darker, heavier, more “serious.” But Talking Book isn’t austere—it’s radiant. It glows. It’s not freedom as rebellion; it’s freedom as fractal bloom. A riot in color. And that’s a form of revolution too. Refusing to be consumed by bitterness. Refusing to explain yourself. Refusing to lock the past into narrative. Instead: groove, glitch, prayer, flash, plea, sigh.

You hear this flowering in others. The spaciousness of Talking Book is echoed in the breath between Lauryn Hill’s verses. You hear its suspended intimacy in Frank Ocean’s Blonde, its hybrid tonalities in Solange’s A Seat at the Table, its fractured funk in Thundercat, in Blood Orange, in Moses Sumney. The influence isn’t linear. It’s textural. You hear it when an artist decides that structure is optional, that expression is plural, that truth has rhythm but no outline.

But still—there is only one Talking Book. And maybe that’s the point. It was never trying to be repeated. It wasn’t the beginning of a movement. It was the sound of a man, finally alone with his machines, his memories, his desires, his country—and enough time in the studio to put them all in dialogue.

The Nearness of the End: Death’s Pulse Beneath the Groove

You don’t need to hear the word “death” on Talking Book to feel its presence. It’s there from the first line: “I feel like this is the beginning…” The joy is already haunted. That’s the trick. Wonder sings as if everything he loves might vanish mid-note. And maybe that’s why he holds each note just a little too long, slides through it, lets it shimmer, as if to say: stay.

Even the love songs ache with premonition. “You and I (We Can Conquer the World)” should be triumphant. But it’s so slow, so solemn, it feels like a wedding vow whispered at the edge of a cliff. It’s not a march forward—it’s a tether to something fragile. Or “Blame It on the Sun,” where memory starts to fall apart, and grief looks for a cosmological scapegoat. The loss isn’t named. But it’s total. You can feel the shape of someone who’s no longer there, even if the lyrics pretend it’s just about heartbreak.

The funk, too, has its shadow. “Maybe Your Baby” grooves hard, but it doesn’t lift. It drags. The bass growls, the keys loop obsessively. Stevie’s voice comes through like someone trying to laugh to keep from unraveling. There’s a moment—just for a few bars—when everything drops out but the clavinet, and it’s not music anymore. It’s insistence. You feel the loop of obsession, of betrayal, of mortality as repetition. Not romantic. Compulsive. Death isn’t just an end—it’s a pattern.

Even “Superstition”, so often taken as fun, is a warning. Not just against belief, but against the machinery of causality. Do this, that happens. Trust that, lose everything. The rhythm is infectious—but what it carries is doubt. “When you believe in things that you don’t understand, then you suffer.” That’s not a hook. That’s a prophecy. He’s not just talking about magical thinking. He’s talking about living in a world where logic breaks, where truth fractures, where history repeats and forgets you.

And then there’s the final track: “I Believe (When I Fall in Love It Will Be Forever).” It sounds like closure. Like hope. But listen closely, and the structure begins to fracture. After the chorus, the song doesn’t end. It erupts. A sudden burst of synths, background vocals, almost gospel—except there’s no church. No heaven. Just a kind of radiant panic. A scream disguised as celebration. It’s ecstatic, yes—but ecstasy is not safety. It’s what happens when feeling exceeds the body. And the body, you realize, won’t last.

Talking Book knows this. It never says it. But it knows: the parade is short. The love might be long, but the moment won’t hold. Everything here is touch-and-go. Sung once, maybe never again. That’s why it grooves. That’s why it weeps. That’s why it refuses to conclude. Because something’s always ending.

Opening the Book Now

Listening to Talking Book now is almost too much. Like opening a novel you’re not ready for. A voice you don’t deserve yet. You press play, and suddenly you’re in it—not just hearing songs, but inhabiting something. The world shifts. Breath slows. The edge of the moment gets porous. You remember that music can do more than entertain or console. It can generate—not feeling, but life. Not narrative, but atmosphere. You’re not just listening. You’re inside a new emotional physics.

Because Talking Book doesn’t tell you what life is. It lets you feel what it’s like to be alive—fully, fleetingly, foolishly. It pulls you in, lets you go, curls back around. It weeps without collapsing. It loves without illusion. It grooves in grief. It makes time feel strange and beautiful again. And for just a moment—through headphones, through speakers, through the little space between his voice and your breath—you’re reconstituted. Not fixed. But re-formed.

This is not nostalgia. It’s not reverence. It’s contact. With the possibility of being moved. Of remembering that affect is not escape—it’s entry. That sound, when shaped with enough soul and friction, can become a way of stepping back into the world with less certainty and more sensation. Talking Book doesn’t end. It never ends. It just keeps becoming.