Ferris Bueller’s Oppressive Charm: Nietzsche, Neoliberalism, and the Politics of Joy

By J. Owen Matson, Ph.D.

Introduction: Ferris Bueller, Nietzschean Ethics, and the Affective Unconscious of Neoliberalism

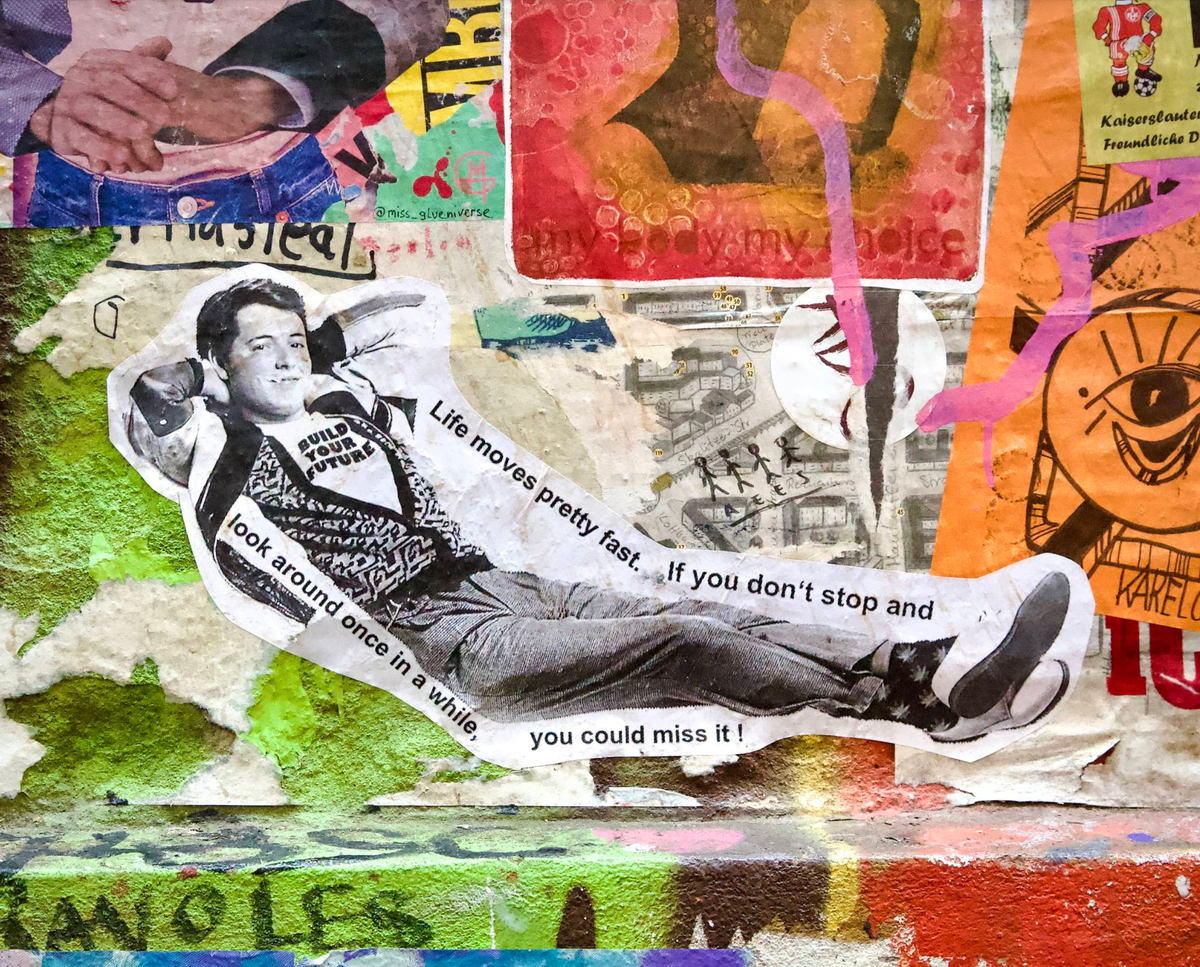

On first viewing—or perhaps the seventeenth, depending on one’s adolescence—Ferris Bueller’s Day Off presents itself as a breezy bit of Reagan-era mythmaking, lightly dusted with Nietzschean ethics for the philosophically curious. Its protagonist, a suburban demigod in white trainers, appears to glide above the moral architecture of ordinary life with the serene self-assurance of someone who has never encountered a consequence he couldn’t charm his way out of. Guilt slides off him like water off a waxed Camaro. Obligation is someone else’s burden. He moves through the world as a kind of free-floating principle of spontaneous enjoyment. It’s a performance of vitality so frictionless that one might, in a moment of theoretical enthusiasm, mistake it for a metaphysical achievement.

The supporting cast obliges this reading with almost allegorical clarity. Cameron sulks in the corner like a living footnote to On the Genealogy of Morality, riddled with guilt and unspoken paternal trauma. Rooney flails about with the brittle zeal of a low-level functionary in a Kafka story, mistaking petty discipline for cosmic order. Jeanie conducts a one-woman crusade against injustice in the domestic sphere, only to find herself thwarted by the fact that no one else seems to care. And Sloane drifts in and out of the action with the calm detachment of someone who knows she’s in the right movie but perhaps not the right century.

So far, so Nietzschean. And yet, like most elegant interpretive frameworks, this one begins to unravel as soon as you look at it for too long. Ferris’s freedom, for all its dazzle, turns out to be less a metaphysical condition than a relational strategy. His joy, such as it is, doesn’t radiate from within—it depends on an elaborate emotional economy, one in which others are cast, willingly or not, in the role of anxious dependents, moral foils, or grateful spectators. What initially reads as spontaneous vitality begins to look suspiciously like infrastructure: a carefully maintained affective regime whose success relies on the quiet labor of those who don’t get a parade. Far from affirming Nietzschean ethics, the film ends up quietly sabotaging them. It doesn’t reject the Übermensch; it simply shows us what happens when he has a student parking pass and parents who buy him a computer.

This essay, like Ferris himself, begins with an air of untroubled confidence—glancing sideways at Nietzsche before sauntering off into more crowded theoretical territory. At first, it contents itself with a familiar itinerary: tracing the contours of joy, resentment, and moral theatre across a cast of characters who often resemble philosophical concepts more than fully furnished human beings. But theory, like adolescence, rarely proceeds in a straight line. What begins as a brisk diagnostic stroll soon becomes a recursive detour, as Hegel shuffles in with his dialectic, Foucault lurks in the background reorganizing the school’s disciplinary apparatus, and Berlant, uninvited but essential, arrives to explain why none of it ever feels quite as liberating as it looks on paper. Each frame of analysis arrives not to settle the matter but to gently embarrass its predecessor, in the manner of academics at a conference panel who all insist, politely, that the previous speaker has “raised important questions” before entirely ignoring them.

What emerges from this increasingly overdetermined procession of theorists is not so much a reading of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off as a quiet reckoning with the inadequacies of ethical theory when confronted with the mess of emotional asymmetry and historical convenience. Ferris, once hailed as a lovable rogue or a teenaged Übermensch, begins to look more like a well-meaning HR manager in the affective sector—tasked with organizing everyone’s feelings into something upbeat, Instagrammable, and safely non-disruptive. He doesn’t merely charm; he arranges the encounter so that charm becomes the prevailing logic. The rules aren’t broken so much as dissolved into an atmosphere where their relevance quietly fades. What he governs is less behaviour than the ambient conditions under which behavior unfolds.

The film, to its credit, never quite buys its own fantasy. Its most honest moments occur at the edges—where the joy begins to falter, where care slips into command, where freedom starts to look suspiciously like a management style. If there is a truth to be found here, it lies not in Ferris’s parade or his platitudes, but in the quiet suggestion that liberation, in its contemporary packaging, may require the cheerful misrecognition of those whose labor—emotional, narrative, or otherwise—makes it seem effortless. Ferris may get the last word, but the story’s conscience is elsewhere, probably still sitting in the wreckage of a vintage Ferrari.

Here is your revised passage in the voice of Terry Eagleton: dense but never ponderous, amused by its own critical apparatus, and subtly irritated by the triumph of mood over meaning. The cadence is unhurried, the irony baked into the syntax, and the humour rides just beneath the surface like a submerged smirk:

What I’m calling the film’s affective unconscious owes a methodological debt, as all respectable diagnoses of cultural pathology must, to Fredric Jameson’s political unconscious—that grimly persistent reminder that even the fluffiest of cultural artifacts is quietly bearing the psychic weight of historical contradiction. Jameson, who never met a text he couldn’t turn into a class struggle with a subplot, proposed that all narratives, however personal or pastel-coloured, are busy encoding the disavowed anxieties of their moment. It is not simply that history intrudes into culture, but that culture, like a bashful teenager caught with a philosophy book, tries to hide the intrusion behind a well-timed joke.

In this light, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off begins to look less like a comedy about adolescent hijinks and more like a moodboard for emergent neoliberal subjectivity. The film does not speak the name of neoliberalism—few things from the 1980s ever did, except Margaret Thatcher and, on occasion, furniture—but it is unmistakably fluent in its dialect. What it offers is not ideology in the old-fashioned sense, complete with slogans and manifestos, but something far subtler and more pernicious: a regime of feeling, in which spontaneity is curated, vitality is moralised, and charm is quietly weaponised as a tool of social coordination.

We are not told explicitly how to feel about Ferris, but we are gently positioned to agree that anyone who doesn’t enjoy his antics is probably some form of bureaucratic malcontent. Joy is compulsory, but in a non-binding, plausibly deniable sort of way. The real lesson of the film, if one can call it that, is that freedom needn’t be argued for when it can simply be performed—and that those who fail to keep up emotionally are probably holding everyone else back. If Jameson urged us to read texts symptomatically for their buried political content, this essay might be said to attempt a kind of affective symptomatology: tracking how the cheerfully delinquent figure of Ferris Bueller comes to embody a world where charm is no longer a personality trait, but a minor function of governance.

The affective machinery on display in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is not merely a product of its characters’ psychological dispositions, but of a broader cultural climate in which optimism had been elevated from a personal virtue to a national strategy. Released in 1986, the film belongs squarely to the late Reagan era, a time when the president’s most significant political achievement was to make the dismantling of public institutions feel like a sunny afternoon barbecue. Reagan, who managed to combine the charisma of a television host with the policy instincts of a Victorian factory owner, perfected the art of smiling while things quietly fell apart. His public persona, equal parts genial patriarch and avuncular ghost, offered Americans a vision of authority so affectively well-lubricated that it was easy to forget what, precisely, it was presiding over.

In this context, Ferris Bueller appears less as a charming adolescent than as a kind of hormonal emissary of a broader ideological regime. His irrepressible cheerfulness, his frictionless mobility, his charming refusal to take anything seriously—all of it reads as a junior-varsity rehearsal of the Reagan affect: control dressed up as charisma, economic privilege mistaken for spontaneity, and moral irresponsibility reframed as emotional intelligence. Like Reagan, Ferris is adored not in spite of his indifference to structure, but because of it. That indifference, after all, is the point. The world is not changed by confronting it, the film implies, but by floating above it with a good pair of sunglasses and an uncanny ability to be somewhere else when the bill arrives.

The film does not offer a political argument so much as a mood, and the mood is one of unexamined ease. It does not ask whether freedom is available to everyone, but simply assumes it comes standard with the right suburban ZIP code. The emotional economy of the story is Reaganomics with a brass section—affective surplus redistributed upward, while those who labour under the weight of guilt, anxiety, or structural constraint are reduced to comic foils or background noise. Ferris, in this telling, is not just a teenager who gets away with everything. He is the cheerful frontman for a system that never had any intention of holding him accountable in the first place.

To make this claim, the essay proceeds in five movements:

- First, it maps the film’s Nietzschean coordinates, framing Ferris as the performative ideal of unburdened becoming.

- Second, it turns to Hegel to reframe the relationship between Ferris and Cameron as a failure of recognition, where care masks dependence.

- Third, it introduces Foucault’s theory of neoliberal subjectivity to show how Ferris’s freedom is not transgressive but optimized.

- Fourth, it draws on Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism to expose the emotional cost of this ethic—the demand to convert suffering into cheerfulness.

- Finally, it synthesizes these insights to reveal the deeper structure: Ferris’s liberation is not universalizable, because it is built on the soft coercion of charm and the silent labor of others.

The result is not a denunciation of Ferris, nor a reversal of the film’s pleasures, but a deeper ethical question: What kind of freedom is it that requires others to perform joy in order to make it believable?

Mapping the Nietzschean Terrain: Characters as Moral Allegories

Plot, in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, is something of a courtesy gesture. The film has one, technically, in the same way a cheese plate might include a sprig of parsley. What it really offers—at least in its opening movements—is not narrative but allegory, a brisk tour of Nietzsche’s moral universe repackaged as a suburban matinee. The characters are less personalities than positions, arranged neatly along an axis of exuberance and inhibition, as if someone had accidentally spilled On the Genealogy of Morality into a John Hughes screenplay.

At the centre of this lightly greased moral carousel is Ferris himself, who embodies the Nietzschean Übermensch with a confidence so frictionless it’s hard to tell whether he’s liberated or simply well-insulated. Ferris does not appear to act upon the world so much as rearrange it according to his own affective weather. His joy arrives fully formed, immune to circumstance, like a metaphysical entitlement. He does not ask permission—largely because no one in his vicinity appears to have the ontological standing to deny it. One suspects that if Ferris were to encounter God, he would offer him a ride in the Ferrari and refer to Him as “dude.”

Orbiting this sunbeam in human form are a cast of auxiliary types, each carrying a different burden of ressentiment. Cameron, the martyr of the piece, moves through life with the posture of a man who has been raised by a punitive deity disguised as a father and has learned to experience joy as an existential hazard. Rooney, meanwhile, is the local magistrate of herd morality, outraged not by crime but by the indecency of joy proceeding unpunished. Jeanie, Ferris’s sister, is less committed to justice than to the quiet hope that someone, somewhere, will finally recognize that she too exists under gravity. Each of them is caught in a reactive circuit, their identities forged not through affirmation but through resistance—though, crucially, resistance to a subject who remains structurally untouched by their refusal.

Only Sloane, composed and vaguely spectral, seems aware that she is in a philosophical allegory. She observes Ferris and Cameron with the calm of someone auditing a course they’ve already passed. She neither resents nor affirms, but simply occupies space with the kind of grace that escapes interpretation. If she appears passive, it may be because she recognizes that the film is not really about her, and has no intention of pretending otherwise.

Taken together, the ensemble assembles itself into a morality play—though one in which morality has been replaced by affective ease, and consequence outsourced to comic misadventure. The narrative arcs gently toward resolution: Ferris dances, Rooney is mauled by a dog, Cameron discovers that destroying a car might be therapeutic, and Jeanie decides that rage, while righteous, is rarely productive. The world, such as it is, bends toward Ferris’s rhythm, and for a moment, all appears redeemed by the sheer buoyancy of adolescent whim.

And yet, as with all successful ideological apparatuses, the charm begins to fray when inspected too closely. Ferris’s freedom, so breezily displayed, turns out to be less a condition of the self than a structure built on others’ constraint. His joy, like all well-funded freedoms, is relationally subsidized. The film may perform vitality, but it does so at the cost of failing to ask who is underwriting the mood. As the Nietzschean scaffolding gives way to more complex emotional entanglements, what emerges is not transcendence, but asymmetry. Ferris does not dominate—he simply assumes. And those around him, caught in the gravitational field of his ease, are left to accommodate, interpret, or implode accordingly.

Ressentiment and the Machinery of Slave Morality

To understand the ethical structure underlying Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, we need to dwell a moment in Nietzsche’s theory of slave morality, a concept he develops most pointedly in On the Genealogy of Morality. For Nietzsche, slave morality arises not from strength but from weakness—more precisely, from the inability to act. It is the morality of the oppressed, the powerless, the injured. Faced with external domination, the subject of slave morality turns inward, breeding an ethics of resentment, guilt, and reversal.

Where master morality affirms life through strength, exuberance, and self-assertion, slave morality redefines power as evil and weakness as virtue. It does not create values—it reacts to them. It does not celebrate its own vitality—it condemns the vitality of others. Nietzsche calls this ressentiment: a reactive posture that transforms frustration into moral judgment. In this sense, morality itself becomes a form of psychological revenge.

This reversal is at once emotional and ontological. The subject of slave morality becomes one who lives in reference to others, whose identity forms through negation. The strong man is redefined as cruel, the joyful perceived as selfish and the sovereign as wicked. In Nietzsche’s provocative framing, the slave does not destroy his master. Instead, he simply renames him “sinner” and declares himself righteous. With this structure in place, we can now return to the film, where each major character dramatizes—sometimes explicitly, sometimes obliquely—a relationship to this moral economy.

Cameron: The Internalized Subject of Slave Morality

Cameron, as Nietzsche would have it, is a model case of slave morality—not because he launches any moral crusade, but because his entire existence has been shaped around the things he dare not do. His passivity is not a failure of nerve so much as the outcome of long-term exposure to a domestic atmosphere in which refusal is unthinkable and silence is a primary instrument of control. The father, who never appears but whose presence is everywhere, exerts power not by shouting but by owning things—particularly a car that functions less as a vehicle than as a theological concept. Discipline, in this household, is administered through upholstery.

Cameron has been trained not to act but to flinch in anticipation of action. He occupies a space in which even the idea of desire seems vaguely improper. His relationship to guilt is not episodic but architectural; it structures the way he moves, speaks, and imagines consequence. There is no one commanding him anymore—there doesn’t need to be. The machinery of moral inhibition has been so successfully internalised that by the time Ferris suggests he “relax,” the comment lands with all the tact of telling a monastic not to overthink their vows. Ferris means well, of course, but his advice presumes a shared world—a world in which joy is accessible, freedom is benign, and pleasure can be summoned like a ride-share.

For Cameron, the problem is not that he doesn’t know how to enjoy himself. It’s that he suspects the entire category of enjoyment might be a kind of trap—one more opportunity to fail in ways he can’t yet anticipate. His suffering is not expressive; it is sedimented. He does not protest, because protest would require a confidence in the self he has never been encouraged to develop. Ferris can improvise a day off. Cameron, left to his own devices, would rehearse an apology for it in advance.

If Nietzsche celebrated vitality as the mark of ethical renewal, then Cameron is a walking reminder that some people have had the vitality trained out of them so thoroughly that even rebellion would feel like a breach of etiquette. His difficulty isn’t the absence of values, but an excess of inherited prohibitions—rules, expectations, silent verdicts—all pressed so tightly into his psychic furniture that they no longer appear as foreign impositions but simply as the way things are.

Jeanie: Resentment with a Smile (and a Scowl)

Jeanie, Ferris’s sister, is what one might call ressentiment in its most performative register. Her objection to Ferris is not grounded in any deep commitment to rules or order, but in the infuriating fact that neither seems to apply to him. It is not that she prizes discipline; it is that she cannot understand how someone so defiantly unburdened by it continues to be rewarded. Her frustration emerges not from a principled moral stance, but from the gnawing suspicion that her own concessions to structure have failed to yield even the minor satisfaction of recognition. In a world where effort appears unrelated to outcome, Jeanie occupies the unenviable position of one who has tried to play by the rules, only to find herself upstaged by someone who does not acknowledge the game.

Her role in the film unfolds along familiar Nietzschean lines. Unable to emulate Ferris’s untroubled ease, she instead becomes his prosecuting voice. She clings to the hope that someone, somewhere, will notice the discrepancy between his behavior and the rewards he receives. This is not justice so much as accounting, a desire to see the emotional books balanced before the film ends. Her resentment, like most resentment of this kind, is both entirely rational and completely ineffective. Ferris does not respond to criticism because he does not recognize it as relevant. He operates in a moral atmosphere where objection has no material consequence, and Jeanie’s outrage, while sincere, is absorbed into the larger comedy as background noise.

And yet the film, perhaps despite itself, offers Jeanie a brief and strange reprieve. This arrives not through familial reconciliation or personal reflection, but through an encounter with a man slouched in the corner of a police station who has apparently opted out of social ambition altogether. The character, played by Charlie Sheen, speaks with the disinterest of someone who has seen too much to bother with judgment. He offers no guidance and makes no demands, but in his disheveled refusal to participate, he provides Jeanie with a glimpse of another kind of freedom. For the first time in the film, she is not being asked to justify herself in relation to Ferris. In the company of someone who neither mirrors nor competes with her, she experiences a momentary release from the closed circuit of moral comparison.

This shift is subtle but telling. Jeanie does not undergo a dramatic transformation, nor does she forgive Ferris or embrace his worldview. What she does instead is far more interesting: she lets go of the need to be seen through opposition. Her identity, no longer tethered to the task of monitoring Ferris’s success, begins to take shape in quieter, less antagonistic terms. The film, in allowing her this small but meaningful turn, suggests that freedom might not always require rebellion. Sometimes it begins with the decision to stop keeping score.

Principal Rooney: The Bureaucratic Face of Herd Morality

If Cameron absorbs suffering as a kind of moral obligation, and Jeanie channels it into private grievance, then Principal Rooney offers the institutional version of the same predicament, dressed up in a corduroy suit and carrying a clipboard. He does not pursue Ferris out of some commitment to justice in any meaningful sense. Justice, for Rooney, is less an ethical imperative than a procedural reflex. What troubles him is not the act of truancy itself, but the unsettling possibility that someone might commit it cheerfully and go unpunished. His authority, such as it is, depends not on the application of rules, but on the belief that rules remain indispensable whether or not anyone follows them. Ferris, with his parade floats and musical interludes, violates not just school policy, but the metaphysical order Rooney has spent a career enforcing.

Rooney’s desire for discipline is not animated by cruelty, although the film is not without suggestions of that possibility, but by a deeper and more embarrassing need for narrative closure. He cannot stand to see the plot unravel. The idea that Ferris might skip school without experiencing some form of retribution is, for him, a breach of the dramatic contract. A world in which such violations are permitted begins to look indistinguishable from chaos, and Rooney, who has no taste for existential ambiguity, takes it upon himself to restore meaning to the situation. His moral worldview is constructed from policy handbooks and breakfast television, a place where cheerful delinquency is always followed by a stern talk in the principal’s office and, if necessary, a letter home.

Nietzsche would have had little difficulty placing Rooney within his moral taxonomy. He is the sort of minor bureaucrat who takes pleasure in enforcement, not because he enjoys confrontation, but because rules provide him with a sense of existential scaffolding. He has no taste for vitality, spontaneity, or contradiction, all of which appear to him as precursors to disorder. Ferris, who seems to operate in a different metaphysical register altogether, represents everything Rooney cannot assimilate. It is not simply that Ferris breaks the rules. It is that he renders them irrelevant by refusing to recognize their authority in the first place. Rooney’s failure, in the end, is not disciplinary but philosophical. He cannot see that Ferris is not playing a game at all, and so continues enforcing the rules of one that no longer exists.

Ferris and the Problem of Slave Morality’s Shadow

At this point, the structure of the film becomes relatively clear, at least on first inspection. Ferris occupies the centre not simply as a character, but as a kind of gravitational force around which others orbit uneasily. The people closest to him—Cameron, Jeanie, and Rooney—are not so much antagonists as reluctant participants in a moral drama whose terms they did not choose. Each of them responds to Ferris in a different register of discomfort, and the common denominator among them is not outrage, jealousy, or even disbelief, but a form of low-grade existential vertigo. Ferris is not burdened by guilt. He shows no sign of interior struggle. His freedom, which arrives so effortlessly, serves primarily to remind others how little of it they themselves possess. He does not need to provoke them directly. His existence, in its cheerful disregard for the rules they have internalised, is provocation enough.

It is tempting to treat Ferris as a kind of adolescent redeemer, gliding into the lives of his companions to help them cast off repression and embrace something like joy. The film often encourages this reading, whether through the narrative arc of Cameron’s minor breakthrough or the sudden, unexplained lightness with which Jeanie concludes her moral campaign. But this vision of Ferris as liberator begins to lose coherence when examined with even modest suspicion. He may not intend harm, but he certainly benefits from the arrangement in which others remain tethered to structures he himself floats above. His interventions, far from being neutral, are often premised on the idea that his perspective is universally applicable. Ferris does not ask whether Cameron wants to change. He simply decides that change is good for him and sets the day in motion accordingly.

The problem is not that Ferris lacks empathy. It is that he does not require it. He is so fully convinced of the value of freedom that he cannot quite see how someone might fail to experience it in the same way. His charm, which the film treats as a natural resource, becomes something closer to soft authority. Others follow him not because he compels them to, but because the alternative would be to remain in the moral stasis they are too tired or too proud to name. If Ferris appears unaffected by the suffering around him, it may not be because he is heartless, but because he cannot quite grasp that joy is not equally distributed. His freedom, in other words, is not universal but contingent. It requires the presence of others whose lack of freedom confirms it. The danger, then, is not that Ferris is a false prophet, but that he is a sincere one, unaware of how much his gospel depends on the quiet labour of those who are left behind.

Ferris and Cameron: Joy’s Shadow and the Ethics of Asymmetry

Cameron and Nietzschean Ressentiment

If Ferris Bueller appears, on the surface, to be a cinematic embodiment of Nietzschean vitality—a figure of joyful, self-authorizing freedom—then his best friend Cameron is his counterweight, both narratively and ethically. Cameron is a study in internalized repression: he is riddled with guilt, immobilized by anxiety, and emotionally dominated by a father who, though absent in the film, exerts total psychic control through silence, possessions, and fear of reprisal. He is the perfect figure of Nietzschean ressentiment—a figure who has come to interpret his own suffering as a form of moral superiority.

Cameron’s virtue lies in his endurance. He endures illness, passivity, disappointment, and abuse with a quiet sense of righteousness. He does not envy Ferris so much as judge him. His frustration with Ferris’s ease is always tinged with moralism: How can he be so carefree? Doesn’t he understand consequences? Doesn’t he realize how much things matter? Cameron’s identity is anchored in caring too much, and that excessive care becomes, in his own view, a kind of ethical high ground. Where Ferris lives lightly, Cameron suffers deeply—and that depth, for Cameron, is what makes him real. More grounded. More serious. More responsible.

“He’ll keep calling me. He’ll keep calling me until I come over. He’ll make me feel guilty… this is ridiculous, OK? I’ll go, I’ll go, I’ll go, I’ll go, I’ll go.”– Cameron, succumbing to Ferris’s pressure in the opening act

This moment captures the mechanics of ressentiment with uncanny precision. Cameron does not assert his will; he narrates his own helplessness. But he also casts that helplessness in moral terms. His suffering should mean something. It becomes the grounds for a subtle claim to ethical insight—the idea that his moral seriousness, born of pain, makes him better than Ferris in some unspoken way. This is Nietzsche’s precise diagnosis: that in the absence of agency, the subject of slave morality converts suffering into a form of value. Unable to change his condition, Cameron finds virtue in the fact that he feels it. His endurance becomes his moral capital.

Ferris’s Fantasy of Redemption

While Cameron transforms his suffering into a quiet moral superiority, Ferris sees it as a problem to be solved, a burden to be lifted through a curated experience of joy. But crucially, he frames this solution as liberation. To Ferris, their friendship is a kind of mission. He believes that what Cameron needs most is to be rescued from himself. Throughout the film, Ferris repeatedly casts himself in the role of the liberator. He sees Cameron’s passivity and anxiety as pathologies to be overcome—ideally, through his guidance. In one of the few moments of emotional directness, Ferris remarks:

“If anybody needs a day off, it’s Cameron. He has a lot of things to sort out before he graduates. He can’t be wound up this tight and go to college. His roommate will kill him.”

In Ferris’s mind, this is compassion. But it’s a compassion that reflects Nietzsche’s own danger zone: the moment when the self-affirming individual begins to prescribe becoming for others. While Ferris’s desire to “fix” Cameron is genuine—in fact intimate, even affectionate—it also reveals Ferris’s underlying dependence on Cameron’s suffering as a kind of narrative foil. For Ferris to feel like the joyful redeemer, Cameron must remain broken—at least long enough to be transformed. He doesn’t just want Cameron to feel better. He wants to be the one who makes him feel better. His vitality needs an audience, a contrast, a cause.

Even the most climactic scenes in the film reflect this dynamic. When Cameron falls into a dissociative state after the Ferrari joyride, Ferris panics—not simply out of guilt, but because his project is breaking down. He doesn’t know how to reach Cameron in that moment, because Cameron’s breakdown is no longer on Ferris’s terms. And once it isn’t, Ferris can’t narrate it into a redemptive arc.

“This was all my fault. I made him take the car. I made him come out with me. How could I have been so selfish?”

This moment is striking—one of the only instances where Ferris speaks in the grammar of guilt. But even here, his remorse is framed narratively: I caused pain, and now I have to undo it. It’s a return to story control, not an encounter with ethical opacity.

Ferris’s role is thus more complicated than trickster or hero. He is a self-styled redeemer whose joy becomes prescriptive. His ethics are aesthetic: life should be beautiful, free, uninhibited. But when those aesthetics become universalized—imposed on a friend who suffers differently—his liberation becomes indistinguishable from pressure. The deeper irony is that Ferris’s power comes not from self-overcoming, but from self-alignment. He has always been free. He has never been oppressed. His vitality is not a hard-won triumph—it is an atmospheric given. Which means his model of freedom cannot be taught. And yet he tries to teach it.

The Contrast of Jeanie: Liberation Without Dependence

Ferris Bueller sees himself as a liberator. He wants to free Cameron from anxiety, guilt, and repression—wants to be the one who makes it happen. But as we’ve seen, that liberatory gesture is not without cost. Ferris’s investment in Cameron’s transformation may be affectionate, but it is also instrumental. It is a performance of freedom that requires someone else’s entrapment to give it meaning. This structure becomes fully visible only when placed in contrast with Jeanie’s arc, and—more pointedly—through her brief encounter with Garth Volbeck (Charlie Sheen), who operates in the film as a quiet but devastating foil to Ferris himself.

Jeanie as Reactive Mirror to Cameron

Jeanie begins the film as a figure of pure ressentiment. She resents Ferris not because he has wronged her, but because he seems to live beyond consequences. Where Cameron internalizes guilt and collapses into inaction, Jeanie externalizes rage and seeks moral correction. Both are trapped in reactive structures, but their orientations differ: Cameron suffers silently and martyr-like; Jeanie lashes out, vigilante-style. Her identity is built around negation. She becomes the self-righteous enforcer of fairness, consumed by the injustice of Ferris’s effortless charm. Ferris’s freedom is not just annoying—it is, for Jeanie, an existential offense.

Garth Volbeck as the Foil to Ferris Bueller

Enter Garth Volbeck: disheveled, soft-spoken, and sitting in a police station holding cell. At first glance, he’s Ferris’s opposite in every superficial way—unkempt where Ferris is polished, anonymous where Ferris is adored. But the deeper contrast is existential: Garth lives without narrative, without charm, without agenda. He is entirely disinvested in performance.

Where Ferris constructs his identity through visibility, Garth doesn’t even seem to care if he’s noticed. He is present, unhurried, unguarded. And because of this, he becomes the only character in the film who can offer Jeanie recognition without moral pressure. Ferris needs others to reflect his vitality. Even his effort to “free” Cameron is part of his broader narrative of joy. But Garth is free precisely because he is uninvested in outcome. He has nothing to prove, and no need to be right.

“You don’t respect him because he threatens your sense of control. He’s popular because he’s good at it. And you’re not. And that makes you angry.”– Garth Volbeck to Jeanie

This line is clinical, unsentimental, and cutting. But it marks the only moment in the film when someone speaks to Jeanie without trying to reform or rebuke her. Garth isn’t attempting to “help” her—he’s simply telling the truth as he sees it. And then, crucially, he lets it go.

A Different Kind of Freedom

Ferris performs liberation through spectacle: parades, hijinks, charm. His freedom is exuberant, and it brings others along—but only if they submit to its terms. Garth offers none of this. His freedom is not flashy—it’s structural. He exists outside the frame of obligation altogether. And that’s precisely why Jeanie changes. Not because Garth makes her change, but because he does not need her to. In his presence, she feels the possibility of existing without opposition. She doesn’t “join” Ferris’s world. She simply stops needing to oppose it. She returns from the police station lighter. Not transformed into someone new, but unhooked from the reactive economy that Ferris, unwittingly, helped sustain. Her smile isn’t Ferris-style joy. It’s something quieter: release.

Reframing Ferris Through Garth

When read through this encounter, Ferris’s dynamic with Cameron becomes clearer. His brand of joy, though seemingly liberatory, depends on others fulfilling preassigned roles. Ferris cannot be the redeemer unless someone else needs to be redeemed. His ethic of vitality relies on a contrast—on others who suffer visibly, so he can perform the miracle of lightness. Garth Volbeck, by contrast, is not trying to redeem anyone. He has no plan, no moral, no performance. And in that absence, a different kind of transformation becomes possible—one that arises from recognition without control. Where Ferris’s charm exerts gravitational pull, Garth’s detachment opens space. The difference is subtle, but decisive. Jeanie’s liberation happens not through persuasion or spectacle, but through indifference that is not dismissal. Garth does not care what Jeanie becomes—and that is precisely why she can become something else.

Dependence Disguised as Liberation

Ferris claims that Cameron “needed this.” That stealing the car, skipping school, and surrendering to experience are good for him. But we must ask: good for whom? Ferris’s fantasy of the perfect day requires Cameron to play his part. He doesn’t take the day off alone—he requires an audience, a companion, a foil. He needs Cameron not only to participate but to transform—because Cameron’s transformation is what gives Ferris’s joy ethical legitimacy.

If Cameron suffers but comes out stronger, then Ferris was right all along. But this structure places Cameron in a morally precarious role: his pain becomes a necessary part of Ferris’s narrative of vitality. Ferris’s push, then, isn’t neutral. It is the imposition of an ontological framework—his—onto someone whose suffering is not only misunderstood but actively denied. This is not cruelty, exactly. It’s a deeper kind of blindness: a refusal to acknowledge difference. Ferris does not treat Cameron as an interior being with a different structure of experience. He treats him as a delayed version of himself. And in doing so, he collapses the possibility of true relational ethics.

A Friendly Repetition of Abuse

This is where the father–Ferris parallel becomes unavoidable. Cameron’s father is distant, controlling, and emotionally absent. Ferris is present, playful, and emotionally expressive. But both exert control. Both assume authority over Cameron’s experience. And both refuse to recognize him on his own terms. Ferris’s charm disguises the repetition of a deeper structure: the inability of Cameron’s relational world to allow for self-definition. His father controls through fear. Ferris controls through joy. But both are forms of domination. Ferris, then, becomes a friendly reenactment of paternal abuse—a “kinder” tyrant whose intentions do not negate the pressure he applies. For Cameron, this relationship may feel like freedom, but it is ultimately a re-staging of the same power dynamic, now softened with affection and wrapped in charisma.

Cameron’s Complicity in the Loop

The tragedy, however, is not simply that Ferris imposes—but that Cameron needs him to. As a victim of emotional neglect, Cameron has no framework for relational autonomy. He has learned to associate closeness with domination, affection with coercion. Ferris does not feel foreign to him; Ferris feels familiar—because Ferris reenacts the only dynamic Cameron has ever known. In this way, Ferris becomes not just a friend, but a site of displaced attachment—a proxy figure through which Cameron negotiates his relationship with his father. Ferris offers the same pattern, but softened: less threatening, more bearable, even intermittently pleasurable.

This is why Ferris’s analysis of Cameron is so cruelly ironic. When Ferris says Cameron “needs to take a stand” against his father, he is speaking truthfully—but without awareness of his own implication in the dynamic. What he cannot see is that, in urging Cameron to break free from domination, he is also urging Cameron to break free from him. Ferris mistakes himself for the solution to Cameron’s problem, when he may in fact be the repetition of it.

Control Without Violence, Dependence Without Acknowledgment

What makes this structure so ethically difficult is that Ferris is not malevolent. He does not abuse in the traditional sense. He does not punish, withdraw, or threaten. But he expects compliance, and narrates that compliance as healing. He reconfigures Cameron’s suffering into a stage for his own redemptive ethos. This is control without violence. It’s dependence without acknowledgment. Ferris needs Cameron to follow, to resist just enough to require convincing, to suffer just enough to be saved. And Cameron, trapped in a structure he cannot yet name, accepts this because it is less painful than rejection—and more familiar than freedom.

Rupture, Not Rebellion: Cameron’s Break

The most significant moment in the film is not Ferris singing in the parade or evading Rooney—it is Cameron, staring into the shattered remnants of the Ferrari. When he says, “I’m going to take a stand,” it’s unclear whether he means against his father, against Ferris, or both. What matters is that, for the first time, Cameron acts without scripting. His decision to destroy the car is not Ferris’s idea. That moment—quiet, trembling, unresolved—is the film’s most authentically Nietzschean gesture. Not because it affirms life, but because it breaks the loop. It is an act of sovereignty, not because it is triumphant, but because it emerges from necessity. Not Ferris’s necessity—his own. This makes the friendship not redemptive, but dysfunctional, even parasitic. And it suggests that the real act of self-overcoming—if such a thing exists—would not be for Cameron to rebel against his father, but to release himself from Ferris altogether.

What Ferris Needs—And What Cameron Doesn’t Get

By reframing Ferris Bueller through Garth Volbeck, and by reading Ferris’s relationship with Cameron as a friendly repetition of abuse, the film’s apparent narrative of liberation begins to collapse. Ferris, once the avatar of carefree vitality, is revealed as a figure of deep dependence—one who needs Cameron’s suffering to sustain both his self-image and the redemptive structure of the day off.

Ferris’s charisma is not free-floating. It’s relationally parasitic. He performs joy not simply for himself, but through others. Cameron isn’t just a friend—he’s the necessary contrast, the living proof that Ferris’s ethic of spontaneity can overcome even the most deeply entrenched repression. But for this ethic to play out, Cameron must remain trapped long enough to be rescued. What Ferris doesn’t see—or cannot afford to see—is that his joy relies on Cameron’s vulnerability. He doesn’t want Cameron to suffer, but he needs Cameron to begin in suffering so that Ferris can bring him out of it. And this quietly turns liberation into instrumentalization.

But the deeper tragedy, as we’ve seen, is that Cameron also needs Ferris—not because Ferris frees him, but because Ferris repeats, in a more tolerable key, the very domination he knows how to survive. Ferris offers proximity, attention, a kind of affection—but on terms that reproduce the asymmetry of his paternal relationship. Cameron doesn’t break free by following Ferris. He breaks free, perhaps, only in the moment Ferris can no longer narrate: the moment the car is destroyed, the moment control—both paternal and friendly—is symbolically shattered.In that act of destruction, Cameron exits the loop—not just of his father's abuse, but of Ferris’s soft domination. Ferris’s role, then, is not simply incomplete—it’s ethically misaligned. He cannot recognize Cameron’s suffering because he has never had to reckon with his own. He lives beyond guilt because his world has never asked him to carry its weight. His joy remains untested, and in this way, his freedom is never truly earned.

Nietzsche’s Blind Spot: The Ethics of Asymmetry

The ethical failure at the heart of this story is not intention but asymmetry. Ferris is not cruel. He is just unburdened. And Nietzsche, for all his radical revaluations, gives us no real tools to think through this condition. His focus is on the individual becoming—the act of self-overcoming, the dissolution of herd morality, the creation of new values. But he does not ask what happens when one person’s becoming becomes another’s constraint.

There is no room in Nietzsche for the emotional economy of the charming oppressor—for the redeemer whose freedom depends on the quiet compliance of others. Nor does Nietzsche dwell in the reality that some selves must, at times, repeat their trauma in subtler forms before they can exit it entirely. Garth Volbeck offers a glimpse of a different freedom—detached, uncoercive, radically non-instrumental. He does not need others to change, and so change becomes possible. Ferris, by contrast, needs others to follow—and so, unwittingly, he reasserts control.

The film leaves us with no easy resolution. Ferris gets away with it, again. Cameron stands quietly by the wreckage. Jeanie smiles, but we don’t know why. And that, perhaps, is the film’s final gift: it refuses redemption on Ferris’s terms, even as it lets him run home. In the end, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is not a fable of freedom—it’s a case study in the limits of joy as an ethic. It shows us what happens when vitality masks dependence, when charm conceals asymmetry, and when liberation, to be real, must begin with recognition—not just of self, but of others. But there is another way to read this—a different philosophical framework that clarifies not only Ferris’s dependence, but the emotional logic of Cameron’s rupture.

Recognition and Revolution: A Hegelian Reframe

Once we recognize that Ferris’s joy is dependent on Cameron’s suffering—and that Cameron, in turn, depends on Ferris to lend structure and tolerability to a world shaped by domination—Ferris Bueller’s Day Off begins to resemble not just a Nietzschean fable of failed vitality, but a Hegelian drama of asymmetrical recognition. In The Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel’s master-slave dialectic describes a dynamic in which the master seeks confirmation of his power from a subject who is not free to offer it. The master depends on recognition, but the slave is denied full subjectivity. This recognition is structurally hollow—affirmation without agency.

Ferris occupies this role perfectly. He orchestrates the world around him and demands that others respond—playfully, gratefully, joyfully. He believes himself to be generous, benevolent. But what he seeks from Cameron is not friendship—it’s legitimization. He wants to be the redeemer. He wants Cameron’s liberation to be his achievement. But recognition from someone who has been coerced into transformation is not recognition at all. It is, at best, a kind of reflected illusion.At worst, it is domination by another name. Cameron, for his part, is not fully aware of this structure. Like Hegel’s bondsman, he endures. He internalizes constraint, and gradually, imperceptibly, begins to define himself by that endurance. His occasional grumbling is not simply a moral posture—it’s a protest that his suffering goes unseen. It’s the longing for acknowledgment from someone who insists on knowing him too easily.

The Ambiguous Break: Rupture Without Form

When Cameron destroys the Ferrari, the moment is charged with symbolism—but ambiguous in its meaning. Is this self-overcoming? Is this emancipation? Or is it simply collapse? In Hegelian terms, a revolution occurs when the oppressed becomes conscious of their position and acts to transform it. But Cameron does not act with that clarity. His break is not ideologically grounded, not directed at Ferris or his father—only at the unbearable feeling of subjection itself. It is not rebellion with a goal. It is rupture without orientation. A scream, not a manifesto. Cameron does not emerge joyful. He does not appear changed in any clearly liberatory sense. He simply exits the loop, without yet entering anything else. The subject has broken free of constraint—but has not yet found a form.

Failed Recognition as the Emotional Core

This reading reframes the entire film as a story of failed mutual recognition. Ferris thinks he understands Cameron, but really, he needs Cameron to remain broken enough to complete his own arc. Cameron thinks Ferris might save him, but what he actually needs is to be seen—not managed, not redeemed, but recognized.

And this failure goes both ways. Ferris receives praise and adoration from everyone except Cameron. And Cameron, for all his suffering, never fully articulates what he needs from Ferris. Each withholds from the other the one thing that could transform their dynamic: recognition that is neither instrumental nor reactive. Only Garth Volbeck comes close to this. His disinterest, his total lack of agenda, makes him the only person who sees Jeanie without projecting onto her. That seeing, which offers no script, is what makes her change possible. In this light, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is no longer a simple drama of rebellion or joy. It is a meditation on the structures of emotional domination that masquerade as care, and on the slow, inarticulate longing for liberation that neither Nietzsche nor Ferris are prepared to understand.

Conclusion: From Nietzschean Vitality to Neoliberal Performance

Nietzsche gives us a powerful vocabulary for reading Ferris Bueller: ressentiment, self-overcoming, the Übermensch. These concepts help us map the film’s moral terrain and its characters’ affective economies. But there are limits to what Nietzsche can show us. His critique operates at the level of values and metaphysics—it diagnoses the pathologies of moral systems but leaves untouched the historical architectures through which certain forms of freedom become legible, desirable, or even possible. Ferris appears to embody Nietzschean vitality—charm in excess, joy without guilt, a refusal to ask permission. But what if that joy is not simply philosophical? What if it is infrastructural? Not an ethical choice, but a historically produced mode of subjectivity? Ferris does not invent his freedom; he performs it. And that performance—carefree, charismatic, frictionless—is not outside of power, but thoroughly shaped by it.

To understand what kind of subject Ferris really is, we need to move beyond Nietzsche’s metaphysical binary of strength and weakness and into a framework that accounts for how freedom itself is structured. This means turning to Michel Foucault’s theorization of neoliberal subjectivity in The Birth of Biopolitics, where freedom becomes the internalized grammar of self-optimization. And it means attending to Lauren Berlant’s critique of affective labor in Cruel Optimism, where emotional attachments to the fantasy of the good life become mechanisms of control. Ferris’s vitality may look Nietzschean, but its conditions of possibility are far more recent—and far more political. His ease is not the residue of metaphysical overcoming. It is the perfected performance of a subject trained to manage affect, curate spontaneity, and govern others through charm.

Foucault: The Neoliberal Subject and the Governance of Affect

In The Birth of Biopolitics, Michel Foucault outlines a transformation in the logic of governance. Power no longer operates solely through restriction or prohibition; it reconfigures itself as freedom. Under neoliberalism, the subject is not merely allowed to act—they are compelled to optimize. The individual becomes, in Foucault’s words, “an entrepreneur of himself,” constantly calibrating their actions, affect, and aspirations within a framework of market logic. Responsibility is no longer about obedience to external authority—it is about internal alignment with conditions that appear natural, even pleasurable.

Ferris Bueller is often mistaken for a figure of rebellion. But what he performs is not refusal; it is the entrepreneurial self in its most frictionless form. He curates the day as if it were a product, selects experiences as if from a menu, and scripts affective responses—for himself, for Sloane, for Cameron—as if directing a brand story. His confidence does not emerge in opposition to power, but from total fluency within its new regime. He does not defy the system; he exemplifies its most seductive logic: that control can feel like freedom if it is performed joyfully.

The “day off” is not a break from structure. It is structure performed as pleasure. Ferris’s spontaneity is not a disruption of norms—it is the enactment of a neoliberal ideal: the self as project, as performance, as affective capital. Every action—hijacking the car, singing in the parade, outwitting Rooney—is both an event and an optimization. He maximizes visibility, manages risk, and generates surplus joy. In this light, Ferris’s ease is not ethically neutral. It is a position within a historically specific regime of subjectivity, one in which autonomy is reframed as aesthetic calibration and responsibility becomes indistinguishable from performance. He is free—but only in the way a well-branded product is free: by fitting perfectly into the logic that makes its circulation possible.

Berlant: Cruel Optimism and the Performance of Joy

If Foucault gives us the structural logic of neoliberal subjectivity, Lauren Berlant gives us its affective atmosphere. In Cruel Optimism, Berlant defines optimism not as hope or desire in general, but as a specific kind of attachment: one that binds the subject to a fantasy of the “good life” that, paradoxically, blocks the conditions for flourishing. These are not illusions we naively cling to—they are structures we inhabit. And even when they harm us, we often prefer their discomfort to the uncertainty of detachment. Ferris’s joy is precisely this kind of attachment. It promises liberation, ease, spontaneous connection—an image of life unencumbered by obligation or pain. But that promise comes with a cost. For Cameron and Jeanie, Ferris’s joy is not a shared condition but an imposed horizon. It sets the emotional terms of the scene. His optimism does not just uplift; it organizes the affective space around him, making dissent or dissonance appear not just inconvenient, but unintelligible.

This is where the optimism turns cruel. It refuses to recognize suffering that cannot be metabolized into redemption. Cameron’s dissociation is treated as something to be solved, Jeanie’s rage as something to be softened. Their discomforts must either resolve into Ferris’s narrative arc or remain pathologized. There is no space for non-conforming affects—no space for emotional realities that do not eventually align with joy. Berlant reminds us that optimism, when framed as moral necessity, becomes a form of governance. It demands lightness, composure, and gratitude, even when those affects are injurious. Ferris does not wield authority in any formal sense, but his affective economy operates as a soft mandate: be playful, be spontaneous, be fine. And for those who cannot, the implication is failure—not just emotional, but ethical.

Ferris’s charm, then, is not benign. It scripts the good life as a particular performance of affective fluidity. Those who cannot access or emulate that performance—Cameron, Jeanie—are rendered either as projects to be fixed or obstacles to be circumvented. His optimism may be sincere, but sincerity does not absolve its cruelty. Following Berlant, we can say it is not the falseness of the fantasy that matters—it is its demand to be lived through, no matter the cost. Within the cultural logic of neo-liberalism, Ferris’s joy is a requirement. He lives in a regime where cheerfulness is not optional, and where others are expected to find their cure in his charm. What Berlant calls cruel optimism becomes, in Ferris’s world, the default moral climate: coercion in the form of care.

Charm as Governance: Affect, Control, and Soft Coercion

Ferris Bueller’s charisma may appear idiosyncratic—his own natural magnetism, a personality trait. But through the lens of Foucault and Berlant, Ferris’s affective mode becomes not merely individual, but infrastructural. His charm functions as a form of soft governance, organizing not only his own experience but the emotional field of those around him. He does not demand obedience. He demands alignment—affective compliance disguised as spontaneity.

Foucault helps us see how Ferris models the neoliberal subject: self-directed, affectively agile, and responsibilized to generate meaning, connection, and pleasure. Berlant, in turn, reveals the cost of that model: the subjects who cannot perform joy are not only excluded—they are rewritten as broken. Cameron’s suffering is not just misunderstood—it is ontologically misrecognized. It becomes illegible within Ferris’s world unless it can be narratively redeemed. This is how charm becomes coercion. Ferris scripts others into scenes of redemption in which their only available freedom is to submit joyfully. Cameron is permitted distress only if it resolves into affirmation. Jeanie is permitted anger only if it is transformed into lightness. Their inner worlds are not encountered—they are edited.

The affective asymmetry is most visible when we contrast Ferris with Garth Volbeck. Garth offers nothing: no joy, no optimism, no script. He does not manage Jeanie’s emotion—he reflects it back, unpolished and uninterpreted. Where Ferris governs through exuberance, Garth offers indifference—not as apathy, but as ethical refusal. He does not attempt to fix Jeanie or fold her into his mood. He does not convert her frustration into narrative value. And in that detachment, he creates the only truly open space in the film—one in which transformation is not prescribed but becomes possible. Ferris’s affective power is seductive, but it is never neutral. His presence restructures the emotional field. His day off becomes the stage on which others are invited to heal—but only by becoming readable to his particular grammar of freedom. It is not violence in any traditional sense. It is something subtler: the conversion of care into control, of joy into mandate, of friendship into affective choreography.

Elation as Ideology: Reaganism, Privilege, and the Politics of Ease

To fully understand what Ferris Bueller’s Day Off stages—beyond ethics, beyond affect—we must return to its historical moment. Released in 1986, the film emerged during the height of Reaganite neoliberalism: an era defined not only by market deregulation and the rollback of public welfare, but by the cultural elevation of optimism as national style. In Reagan’s America, cheerfulness was not just encouraged—it was demanded. Public life was saturated with curated optimism, the charismatic performance of confidence, and the repression of anything that might threaten the spectacle of national vitality.

Ferris is not simply a teenager skipping school. He is the ideological condensation of this Reaganite mood: white, suburban, wealthy, unbothered, and mobile. His joy is not resistance—it is insulation. He navigates a world built for him and moves through it as if friction does not exist. His classroom is irrelevant, his parents are indulgent, the city is his playground, and consequences are always deferred. That his freedom goes unremarked is the point. The film never names his privilege because it doesn’t have to—it is rendered affectively, as ease. Structural advantage is converted into charm. Racial and economic power are performed as personality.

This is not incidental. It is integral. The affective unconscious of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is not simply joy—it is the naturalization of joy as a white, affluent, masculine birthright. There is no poverty in Ferris’s Chicago. No racialized surveillance. No threat of exclusion. Cameron’s father may be emotionally distant, but no character in the film faces systemic constraint. The worst fate anyone suffers is humiliation by a principal or a missed school credit. This is the fantasy world of Reagan’s America: one in which discomfort is a moral failure and happiness is a choice, available to anyone charismatic enough to claim it.

Fredric Jameson teaches us to read these displacements symptomatically—to treat what is not represented as what matters most. In this sense, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is not just a cultural artifact; it is a case study in how ideology masquerades as affect. Its politics are not located in its dialogue, but in its assumptions: the unspoken equivalence between freedom and self-expression, between virtue and vibrancy, between lightness and worth. Amid this fantasy of untroubled white mobility, the two men at the garage—valets who take Cameron’s father’s Ferrari for an unsanctioned joyride—appear at first as comic doubles of Ferris. Like Ferris, they seize the day, claim joy without permission, and navigate the city with exuberant defiance. They momentarily inhabit the same grammar of pleasure: acceleration, escape, spontaneity. Their ride, in fact, mirrors Ferris’s excursion more closely than Cameron’s or Sloane’s. But this mirroring only heightens the limits of the film’s moral imagination.

Crucially, these characters are both men of color. They are given no names, no backstories, no narrative interiority. They exist only in relation to the white protagonists’ property and as a punchline to the film’s affective logic. Their pleasure is not legible as ethical. It is not framed as vitality or creative becoming. It is framed as theft. Their exuberance is excess without justification. Unlike Ferris, who the film insists deserves his joy, the garage attendants are offered no such alibi. The narrative winks at their rebellion but never legitimizes it—ultimately relegating them to the realm of background mischief, safely circumscribed and structurally expendable.

In this way, the garage scene serves as a meta-commentary on the film’s own ideological boundaries. It flirts with the possibility of extending its ethic of joy to nonwhite subjects, only to retract that gesture immediately. Their ride is thrilling, but it is not allowed to signify. It is affect without subjecthood. The men drive the Ferrari, but they are not granted names, backstories, or interiority. Their movement is exhilarating and rhythmic—but it is also narratively disposable. The film contains this doubling by refusing to integrate it, just as it contains any challenge to the whiteness of its vision by rendering nonwhite life as spectacle rather than story. These characters move, but only along the margins of a fantasy world that remains, at its core, stubbornly and uncritically white. The affective unconscious of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is not simply joy—it is the naturalization of joy as a white, affluent, masculine birthright. And as Fredric Jameson would remind us, this is ideology not as deception, but as structure: the film can only imagine joy through the coded grammar of whiteness and privilege, and anything outside that frame must be excluded, aestheticized, or ignored.

Seen in this light, Ferris’s own movement through the city—his confidence, spontaneity, and ease—is not a triumph of the will. It is the cinematic rendering of structural privilege. The freedom he performs is not hard-won; it is infrastructural, inherited, racialized. He drifts through public and private space with impunity, shielded by charm but sustained by social legibility. The fantasy here is not just of rebellion, but of unmarkedness: Ferris is free not because he breaks the rules, but because he never appears as someone to whom rules truly apply. This is what Reagan-era neoliberalism perfected: a cultural economy in which systemic inequality is disavowed, and privilege is transfigured into personality. Ferris doesn’t just get away with it. More telling is that he never has to ask what “it” even is. The film’s ideological work, then, is not to justify Ferris’s behavior. It is to naturalize the conditions that make it possible. And in doing so, it offers a quietly devastating lesson in how structural power operates—not through force, but through the grammar of charm.

Reframing Liberation as Recognition, Not Performance

What Ferris Bueller’s Day Off reveals—once the affective surface is peeled back—is not a fable of liberation, but a case study in soft domination. The film performs joy as ethical clarity, but that clarity fractures under scrutiny. Ferris’s freedom, once read through the frameworks of Foucault and Berlant, is shown to be neither innocent nor idiosyncratic. It is structurally produced, affectively managed, and relationally asymmetrical. It offers a model of care that depends on misrecognition—and a model of liberation that requires others to submit to its terms.

The ethical failure is not that Ferris is selfish or cruel. It is that he cannot recognize forms of experience that do not resolve into the grammar of joy. He performs freedom with such fluency that he becomes unable to register the difference between spontaneity and pressure, between presence and projection. Cameron and Jeanie must be transformed—not for themselves, but to complete Ferris’s redemptive narrative. In this way, joy without recognition becomes domination by another name.

Garth Volbeck, by contrast, offers nothing resembling liberation. He withholds affect, refuses narrative, declines to optimize. But that absence is what makes recognition possible. He does not impose a scene of transformation—he allows for ambiguity. In doing so, he enacts the only ethical gesture the film seems to understand: the suspension of judgment, the refusal to extract value from another’s affect, the recognition of difference that does not require resolution. Ferris is not a villain. He is something more difficult: the neoliberal redeemer, perfectly optimized, affectively fluent, and structurally blind. He collapses the boundary between intimacy and choreography, between vitality and control. His charm functions as governance, and his freedom becomes the template through which others are asked to convert their own suffering into narrative compliance.

In the end, the film does not resolve this tension. Ferris gets away with it. Cameron stares into the wreckage. Jeanie smiles without explanation. And perhaps that is the film’s most honest moment: a refusal to grant Ferris the final word, even as it lets him have the last scene. In a world governed by charm, perhaps the most radical act is not to be joyful, but to be unreadable to joy.

Coda: Sloane Peterson and the Elegance of Non-Alignment

Sloane Peterson occupies a peculiar position in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. She is in almost every major scene, positioned with the aesthetic delicacy of a perfume advert and granted approximately the same narrative depth. Where Ferris improvises, Cameron implodes, and Jeanie is eventually pacified, Sloane does nothing so erratic. She reclines. She walks. Occasionally, she smiles. Her role is not to act but to temper—to provide the soft emotional laminate that allows Ferris’s disruptions to register as whimsical rather than antisocial. In a film organized around transformation, she is assigned no arc, no internal conflict, no climactic release. Her job, so to speak, is to keep the mood intact. She is not a narrative agent so much as a tonal asset: poised, decorative, and ideologically reassuring.

This absence of interiority might appear to be an oversight. But to frame it as a failure of characterization is to misunderstand the structure of the fantasy the film is sustaining. Sloane is not a character who was forgotten; she is a function that was fulfilled. Ferris requires a counterpart who affirms his heterosexual charisma, absorbs no narrative oxygen, and preserves the affective tone of breezy rebellion without ever complicating it. In short, she must be beautiful, agreeable, and affectively efficient. She is positioned less as a person than as emotional upholstery—something to lean on, soft to the touch, already in place before the scene begins. Her grace is not a personal triumph. It is the condition of her inclusion. She glides through the day not because she is carefree, but because she has already been absorbed into the film’s affective infrastructure so fully that any sign of interiority would register as tonal interference.

This structural role is inseparable from its historical moment. In the 1980s, the ideological work of American cinema was to make the contradictions of neoliberal culture appear frictionless. The decade that gave us Reagan’s morning in America also gave us an aesthetic regime built on emotional resolution, suburban coherence, and cinematic protagonists who could disobey every rule while still reassuring the viewer that nothing important was at stake. Ferris is the patron saint of this genre—glibly breaking the fourth wall, outsmarting authority, and treating consequence as a kind of optional subplot. But that genre also requires its enablers—characters who stabilize tone, facilitate legibility, and make charm seem like a plausible substitute for responsibility. Sloane is one such figure. Her function is to anchor Ferris’s charm in the visual idiom of heterosexual romance and to neutralize any dissonance his behavior might produce. That she does so silently, elegantly, and without apparent cost only intensifies the film’s fantasy of frictionless autonomy.

Lauren Berlant’s account of affective life under neoliberalism helps clarify what is at stake here. For Berlant, the good life fantasy—prosperity, freedom, romance, upward mobility—is not just a promise but a demand. Subjects are expected to organize their attachments around these fantasies, even when the structural conditions for their fulfillment no longer exist. Sloane’s composure exemplifies this attachment in its most naturalized form. She performs serenity not because it leads anywhere, but because the scene requires it. Her poise is not a trait; it is a contribution. She supplies the emotional conditions under which Ferris’s antics can be enjoyed without guilt, and Cameron’s breakdown can feel redemptive rather than destabilizing. In this sense, Sloane is the fantasy’s lubricant—ensuring that the machinery of joy continues to run smoothly, even when its ideological seams are beginning to show.

This is affective labor, though the film takes great care not to name it as such. Indeed, the labor’s success depends on its invisibility. Sloane’s smoothness is presented as effortless, as though elegance were simply her nature. But as Berlant reminds us, emotional regulation is never merely personal. It is structural. It organizes how fantasy circulates, who gets to break down, and who must remain composed. Sloane’s serenity, then, is not just an individual performance. It is a systemic requirement. The more convincingly it appears innate, the more effectively it naturalizes the conditions under which others can become legible as subjects.

That this labor is gendered goes almost without saying. Ferris gets to misbehave, Cameron gets to collapse, Jeanie gets to rebel and be reconciled. Sloane, alone, gets to glide. Her primary virtue is that she never complicates the mood. She is a placeholder for intimacy, not a participant in it; a sign of romantic completion without the messiness of emotional need. This is not submission, exactly. It is something more banal and therefore more entrenched: a choreography of composure so well-rehearsed that no one—not even Sloane—can tell where the performance ends.

That work, however, is not without intelligence. Sloane may appear to acquiesce, but the performance is not entirely sincere. Her expressions—measured, ironic, slightly out of sync with the scene—suggest not so much identification as appraisal. She is not swept up in the day so much as attending to its construction. If she seems “in on the joke,” it is not because she finds it funny, but because she recognises it as staged. Her detachment, quiet and non-disruptive, functions as a kind of aesthetic editorializing. She participates in the narrative without quite endorsing it, maintaining a composure that feels less like compliance than curatorial discretion.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the moment when she asks Ferris what they’ll do “next year.” The question arrives without fanfare and is dismissed just as easily. But it punctures the sealed temporality of the film’s fantasy. Ferris’s entire ethos depends on the elimination of consequence. To introduce a future is, in effect, to threaten the system. Sloane’s question cannot be metabolized by the film because it demands a narrative axis—futurity—that the plot has taken great care to disavow. Her intervention is mild, almost imperceptible, but its implications are disruptive. She introduces duration into a story that depends on the eternity of a single, blissfully irresponsible day.

This is not rebellion. It is something more structurally peculiar: a refusal to be incorporated. Sloane does not arc, does not weep, does not confess. She is the only character whose emotional state at the beginning of the film remains intact at the end, which makes her both extraneous and essential. She is a figure of consistency in a plot obsessed with transformation. Her refusal to evolve does not make her static; it makes her structurally incompatible with the developmental grammar of the narrative. She is not a lesson, a risk, or a resolution. She is, instead, an aesthetic condition.

If Ferris is a Nietzschean Übermensch, skipping school with the confidence of one who believes the world exists to entertain him, then Sloane is his Apollonian mirror. She reflects the image but never alters it. Her function is not to intervene, but to sustain coherence—to make rebellion appear composed. She dresses like a character in a shampoo commercial and speaks like someone who has read the script but found it unworthy of annotation. There is wit in her eyes, but it is the wit of distance, not investment. She is not fooled, but she sees no need to spoil the game.

By the film’s end, everyone else has been digested. Ferris has performed his anti-heroism and escaped judgment. Cameron has broken something expensive and declared it therapy. Jeanie has traded resentment for a minor epiphany. Sloane, however, remains untouched. She appears in the closing montage with the same quiet elegance she carried through the rest of the film—unchanged, unbothered, and unexplained. She is, in this way, a surplus presence: not a character whose thread was forgotten, but one whose thread was never supposed to go anywhere in the first place.

Sloane’s ambiguity is not a failure of narrative design, nor simply a gendered omission. It is a constitutive feature of the film’s ideological grammar—a structural necessity that cannot be admitted as such. She must be present to stabilize the mood, to affirm heterosexual legibility, and to buffer Ferris’s excesses with an aura of charm. But she cannot be allowed to signify too much. To grant her an interiority or resolution would be to imply that something was at stake in her presence—that she too inhabited the day with needs, desires, or contradictions. Instead, she is rendered as affective atmosphere, both inside and outside the fantasy she enables. And yet it is precisely this dual legibility—submissive and subversive, decorative and decentered—that marks her as something more than a narrative convenience. She is a remainder produced by the film’s effort to sustain joy as an unproblematic affective good, even as the cultural logic of the 1980s made such coherence increasingly difficult to maintain. Sloane appears composed, but her composure is the symptom of a system unsure of its own emotional ground. Her refusal to resolve is not resistance in the conventional sense. It is the structural return of what the fantasy must exclude: a subject who does not fit, and who makes the neatness of the conclusion feel faintly hollow. She doesn’t conclude. She lingers—too polished to be dismissed, too surplus to be accounted for—an elegant reminder that even fantasies of freedom depend on someone else’s stillness.