Colors in the Dust: Kurosawa’s Dodes’ka-den and the Dream of Survival

Kurosawa’s Dodes’ka-den (1970) is a film of fragments. It offers no central plot, no singular character to follow, and no closure. Instead, it gives us a patchwork of lives at the margins—beggars, drunks, abused wives, unemployed laborers—each stitched into the dusty outskirts of a post-industrial Tokyo. Shot in bright, sometimes surreal color, and framed with an almost theatrical staginess, the film moves like a hallucination: drifting, circling, repeating. It is Kurosawa’s most radical departure from his earlier work, and also, perhaps, his most vulnerable.

The title itself comes from the sound a young boy makes—“dodes’ka-den, dodes’ka-den,”—as he pantomimes driving a streetcar through the wasteland. That sound—onomatopoeic, mechanical, rhythmic—is both game and prayer. The boy, who is neurodivergent and largely ignored by the others, imagines his way into a world of purpose. His streetcar doesn’t exist. The tracks don’t exist. But he believes, utterly. The refrain becomes a kind of mantra, a loop against despair.

And this is the film’s secret heart: not the narratives, not the poverty, but the imagination that pulses underneath. These characters are not just downcast—they are dreaming. They survive through hallucination, denial, ritual, routine. The father who tells his son they are building a mansion inside a rusted car. The drunk who walks in loops. The man who poisons his wife, but believes he is purifying love. Dodes’ka-den does not romanticize these visions. It lets them breathe, crack, repeat. The fantasies fail. The dreams turn. But for a time, they shelter the mind from collapse.

This marks a crucial shift in Kurosawa’s filmography. Where earlier works (Ikiru, High and Low, Seven Samurai) sought moral clarity in a broken world, Dodes’ka-den abandons the quest for redemption through action. There are no heroes here. Only people. Only persistence. The camera doesn’t intervene—it observes. And the film’s color palette, so often jarring—neon oranges, impossible greens, deep purples—serves not to beautify, but to render the real unreal. The shantytown is not a backdrop—it is a psychic space.

Critics at the time were unsure what to make of it. The film was a commercial and critical failure in Japan. Kurosawa fell into depression afterward. But seen now, Dodes’ka-den stands as a raw and necessary work—a portrait of consciousness under siege. It anticipates the move in global cinema toward fragmentation, interiority, and existential drift. And it speaks to something urgent in today’s context: how people live at the edges of systems that no longer see them, how imagination becomes both refuge and delusion, how survival itself can be a kind of madness.

In Dodes’ka-den, the world has already ended. What we see is what remains: memory, echo, color, dust. But the film doesn’t despair. It listens. It hums. It repeats. Dodes’ka-den, dodes’ka-den… A sound made up, but insisted on. A rhythm no one else hears. A streetcar that runs only through the mind—but still runs.

The Intrusion of Color: Kurosawa’s Hyperrealism and the Persistence of Dream

The first shock of Dodes’ka-den is not the setting, not the poverty, but the color. It feels off. Not garish exactly, but unreal—like someone has painted over ruin with crayon or pastel. The shantytown is surrounded by parched earth and scrap metal, but splashed in unnatural hues: electric pinks, acid greens, yellows that seem lit from inside. Clotheslines ripple with color-coded fabric. Walls are painted like schoolroom murals. Even the dust seems tinted. It doesn’t make sense. It shouldn’t. This is not realism. It’s something more unsettling: a technicolor hallucination of survival.

Kurosawa’s first film in color, Dodes’ka-den could have aimed for the subdued palettes of neorealism—muted browns, gray skies, damp textures. But instead, he leans hard into a hyperrealist register, closer to painted storybooks or stage backdrops. There’s a collage-like quality to the set design. Hand-painted, improvisational. Childlike, but not innocent. These colors don’t cheer the scene—they destabilize it. They insist on being seen. They refuse to blend into sorrow.

In this way, color becomes its own commentary on poverty. Not sentimental. Not tragic. Resistant. The children’s clothes are too bright. The houses are painted as if hope were still possible. But the paint is chipped, the saturation inconsistent. It’s hope as gesture, not delusion. Color, here, is not the absence of pain—it’s its companion. Its counterpoint. Its flicker. These are not people who have nothing. They have color. They’ve made it. Found it. Hung it up to dry.

And sometimes, the color intrudes. It breaks the mood, reframes a scene. In the sequence with the father and his son in the car-turned-palace, the backdrop becomes impossibly blue, the sky too wide. We know the mansion isn’t real—but it’s beautiful. The palette turns from washed-out to luminous. In another film, this would signal sentimentality. Here, it’s almost cruel. The color gives, then reminds. You want to believe in the dream—and Kurosawa lets you, for a second. Then he lets the light shift.

The color doesn’t heal. It haunts. Like memory, like imagination, it’s unreliable—but it persists. And this, perhaps, is Kurosawa’s quietest insistence: reality is not enough to account for what people endure. Poverty, when rendered only through grime and grayness, risks becoming invisible. Familiar. Unquestioned. But color makes it strange again. Makes it vivid. Makes it unbearable—not because it’s grotesque, but because it’s too alive.

Dodes’ka-den doesn’t use color as escape. It uses it as tension, as fracture, as a way to show that even in collapse, something still flickers. A red door. A blue shirt. A painted dream. You can’t explain it. But it’s there. Like the sound of an imaginary streetcar. Like a voice saying dodes’ka-den, dodes’ka-den, into the dust.

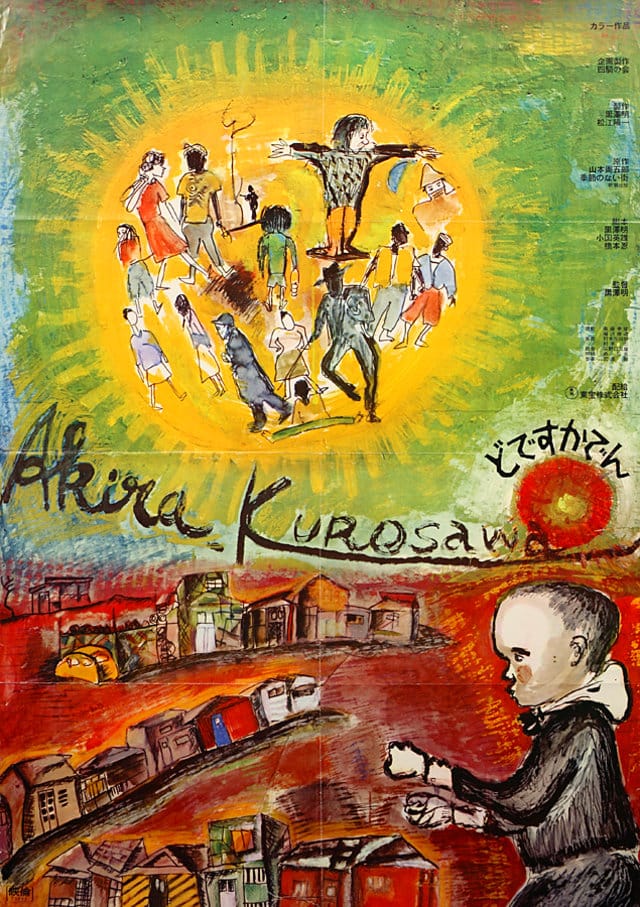

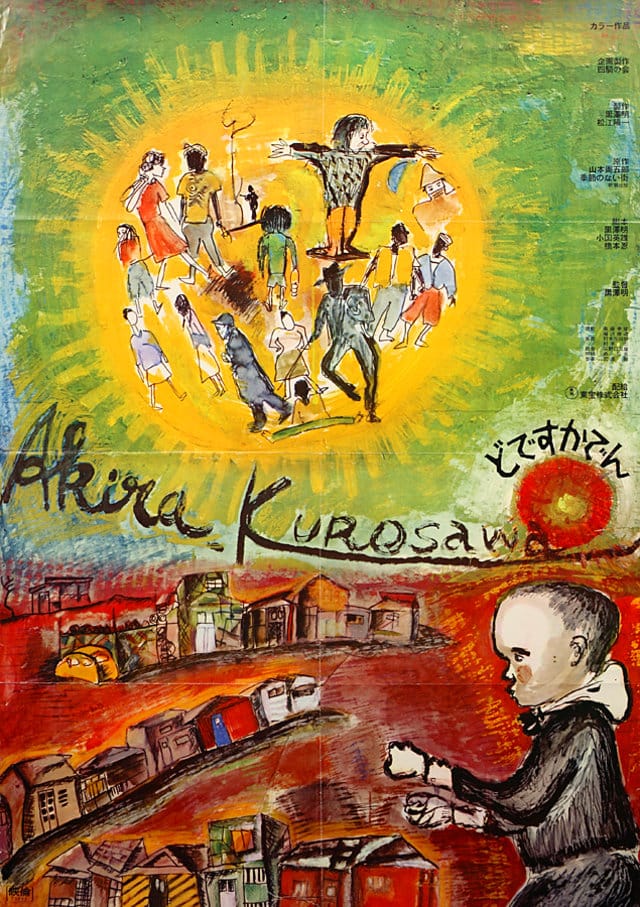

1. Sunburst Theology (bottom, right, Japanese Domestic Poster)

The boy stands at the bottom of the poster, clenching his fists, his body tilted forward in motion. Above him, the shantytown leans like an unstable hill. And above that: a radiant halo of yellow light, at the center of which another child balances on a single wooden plank, arms spread wide. Around him, the community circles, hands joined.

This is not a literal moment from the film. It is a cosmic summary. The boy becomes a prophet. The streetcar mantra becomes gospel. Yet no salvation arrives in the film. The halo is affective, not redemptive. It reflects the spiritual structure of the film—not its outcome. A visual theology without God, only gesture.

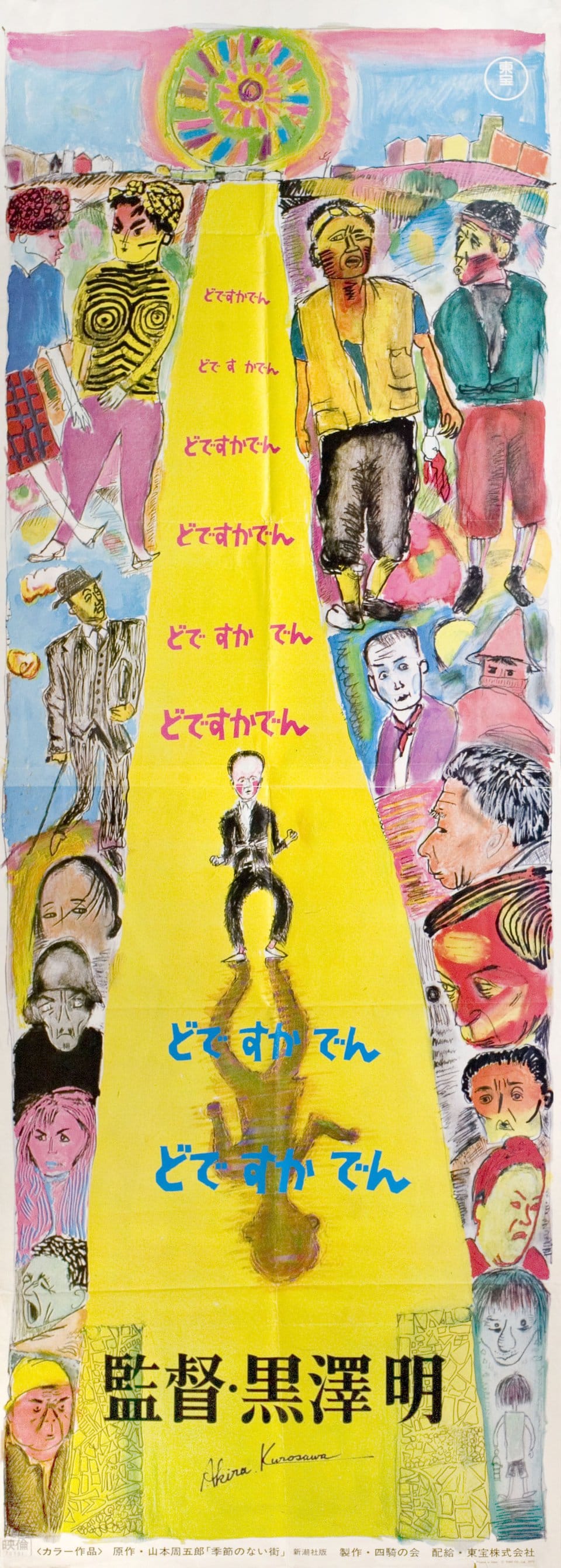

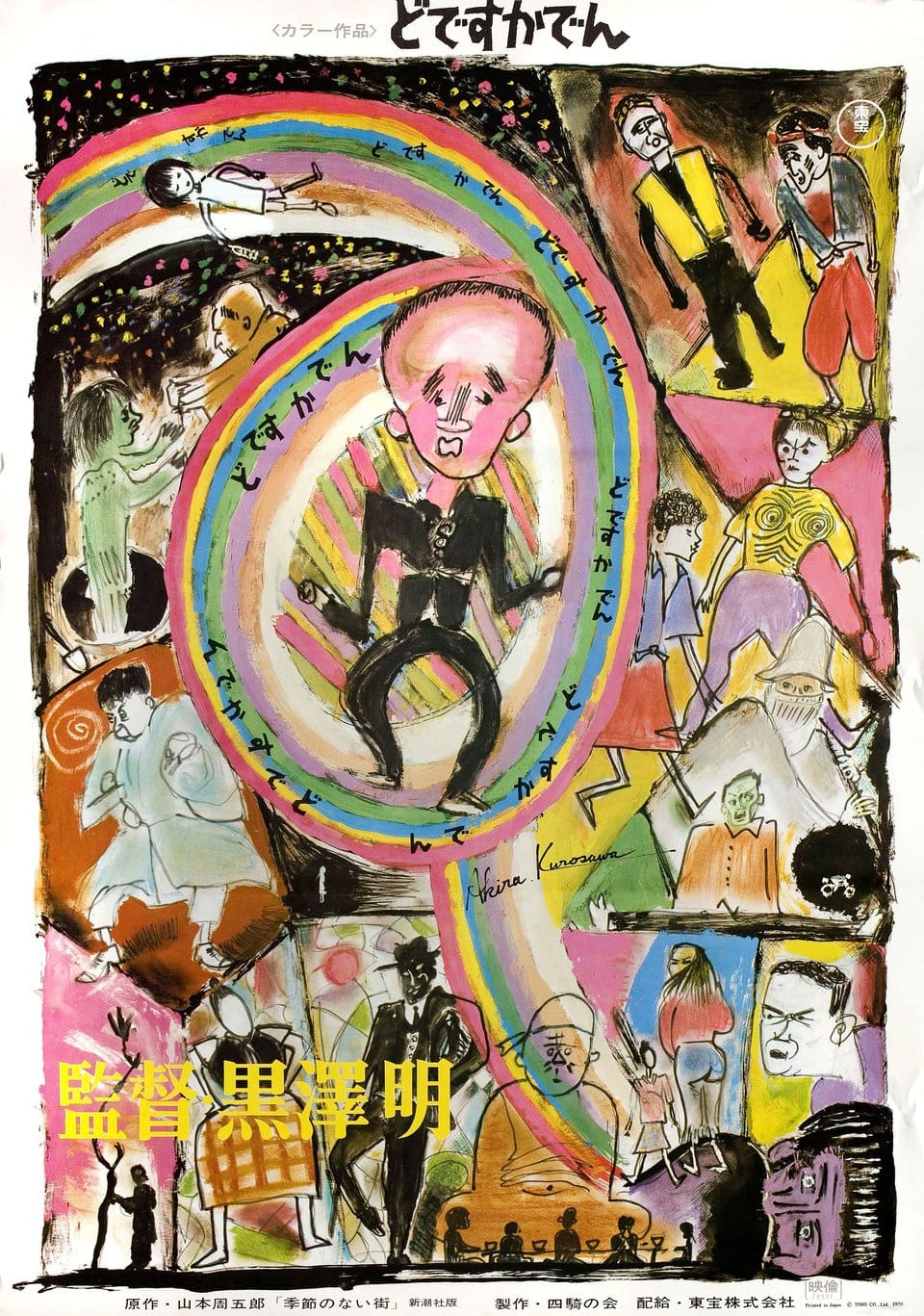

2. The Spiral of Repetition (bottom, left, Japanese Illustrated Poster)

The most chaotic and perhaps truest of all the posters. Rendered in colored pencil and gouache, it places the chanting boy at the center of a concentric swirl. Around him: scenes of domestic abuse, drunkenness, paranoia, love, hallucination. All stylized into grotesque cartoon.

It’s the only poster that captures the film’s rhythm—the claustrophobic loop of madness and memory. The swirl isn’t a rainbow of hope. It’s a visualized chant: dodes’ka-den, dodes’ka-den… again and again. It both contains and dissolves.

This poster is not selling a plot. It’s selling an emotional topology: obsession, color, despair, loop.

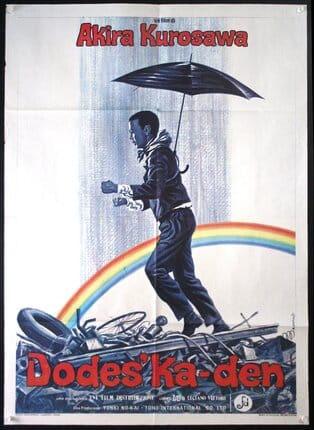

3. The International Translation (top, right, English-Language Poster)

Here, Dodes’ka-den is reframed as a whimsical tale of resilience. A boy walks along a neat arc of scrap metal beneath a rainbow, holding an umbrella like a peace offering. The image is rendered in clean blue monotone, a palette far more subdued than the film ever is.

It’s a misreading, but a revealing one. It shows how difficult the film is to export without distortion. What was psychic collage becomes linear metaphor. But even this softening reveals something about the market’s anxiety toward aesthetic rupture. You can’t sell a film built on fragmentation, but you can sell a boy and a rainbow.

This poster is fantasy about the fantasy—a third-degree fiction.

4. Ascension Strip ( top, left, Japanese Vertical Poster)

An almost architectural composition: a narrow yellow road extends from the boy’s feet upward toward a spiked sun. The boy appears again and again as he chants “dodes’ka-den,” each time slightly different, as if glitching through his own self-image. On either side: vignettes from the film, sketched faces caught mid-expression.

The vertical orientation amplifies the idea of ritual and pilgrimage. The film becomes a scroll, a sutra. The chant becomes the steps of a broken liturgy. Each repetition of the boy signals not narrative progress but ritual persistence.

It’s one of the only posters to see time the way the film sees it: not as movement forward, but as cyclical wear.

Collage and Collapse: The Hand-Painted World of Dodes’ka-den

Look closely at these images. Not just what they depict, but how they’re made.

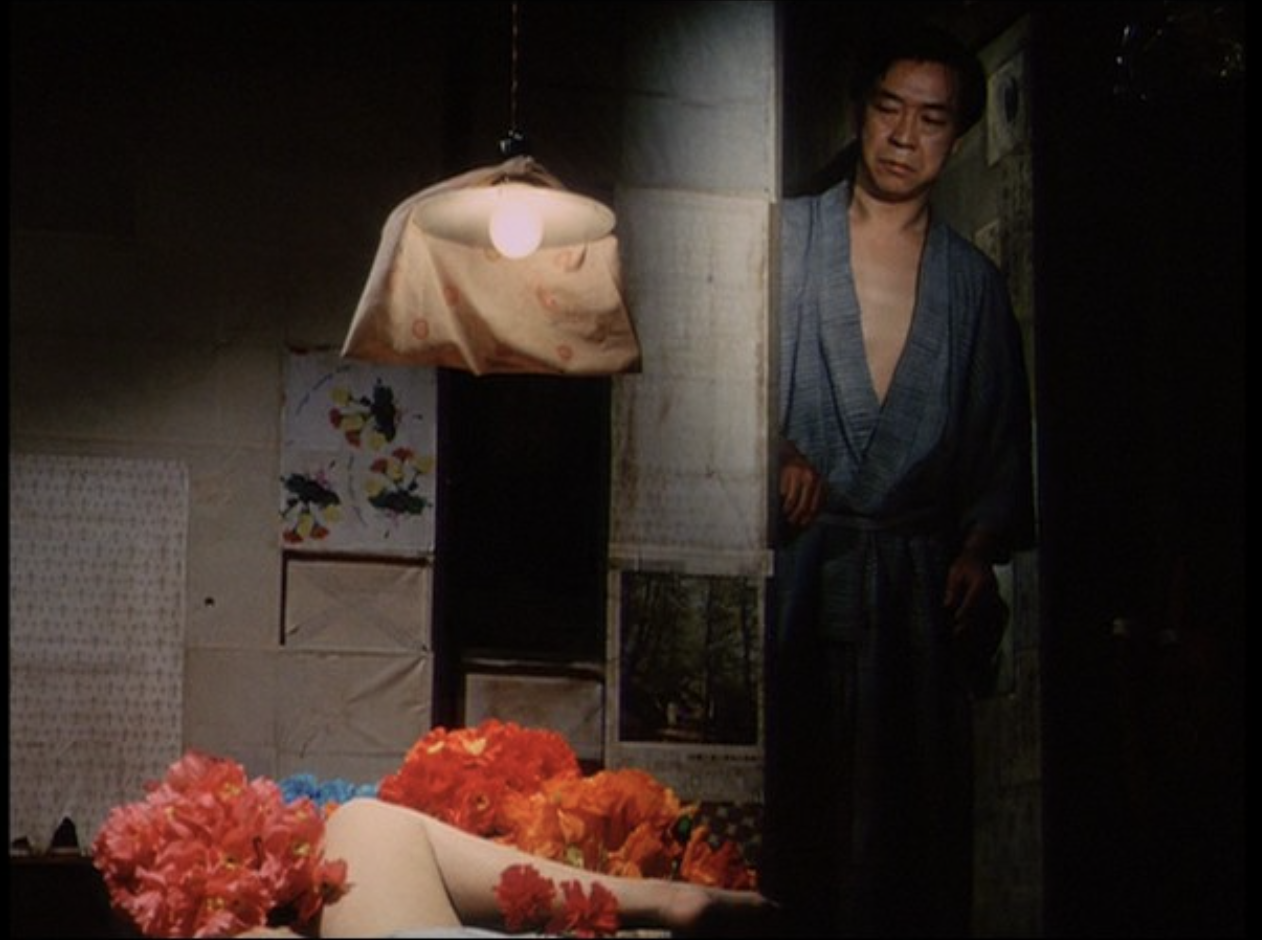

In the first still, the red room: an entire domestic scene assembled out of irregular, patched fabric and painted surfaces. Red dominates—but not one uniform red. Polka dots, floral patterns, layers of saturation and fade, like a worn-out shrine or a memory scabbed over with gesture. The red isn’t just decorative—it pressurizes the scene. These are characters sitting in collapse, but the color refuses to recede. It’s too bright. Too much. It doesn’t console. It provokes. As if the paint is trying to do what the people can’t: hold the scene together.

In the second image, the sky is painted—literally—a brushstroke sky over a backdrop of tires and tin, apocalypse rendered in expressionist sunset. This is not a landscape you wander through. It’s one you fall into. The line between set and psyche vanishes. The child and his father imagine a mansion, but what we see is a ruin made divine by texture. The fantasy has mass. And the paint has memory. The background doesn’t pretend to be real—it declares itself as a projection, a belief, a plea.

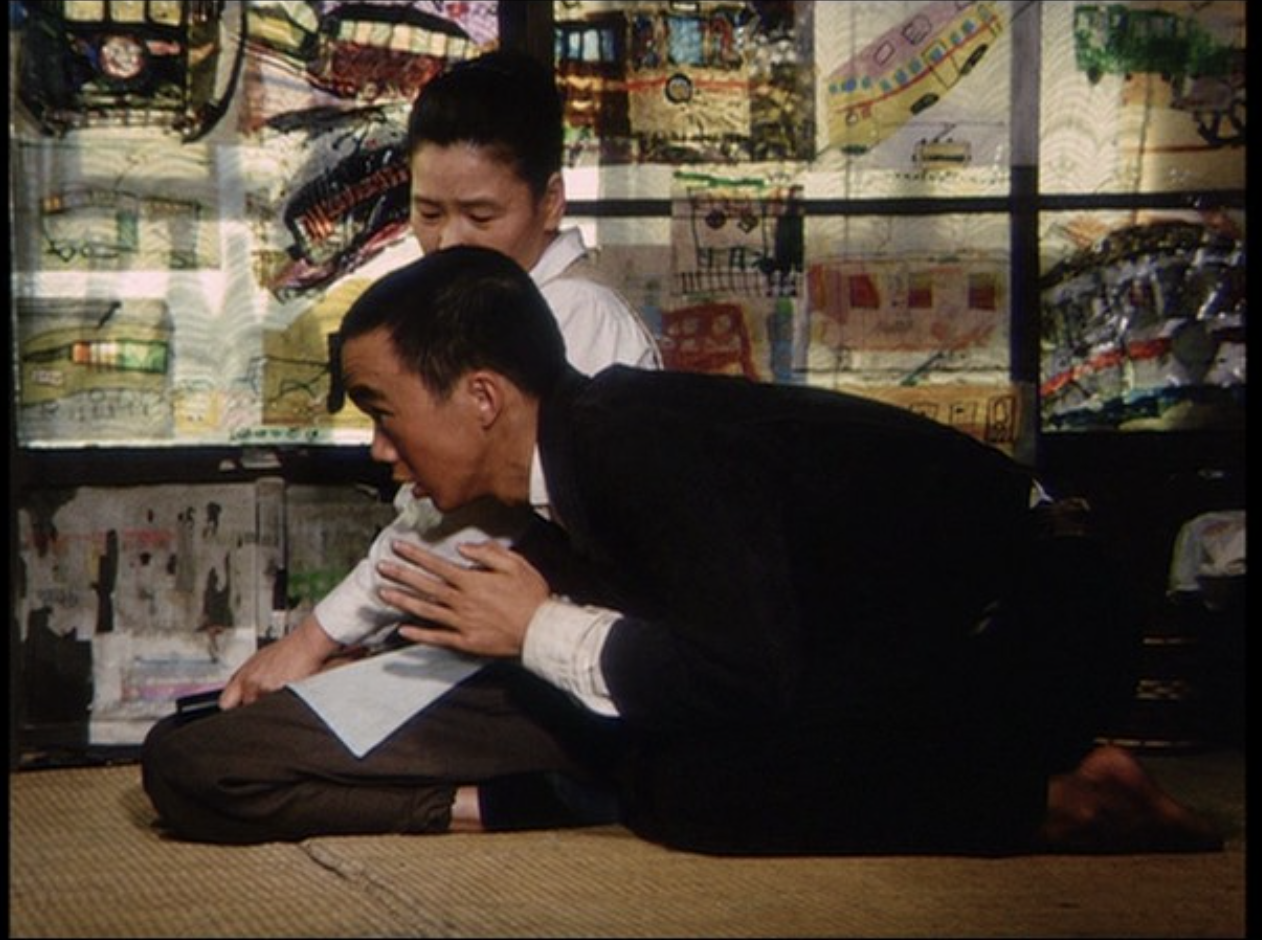

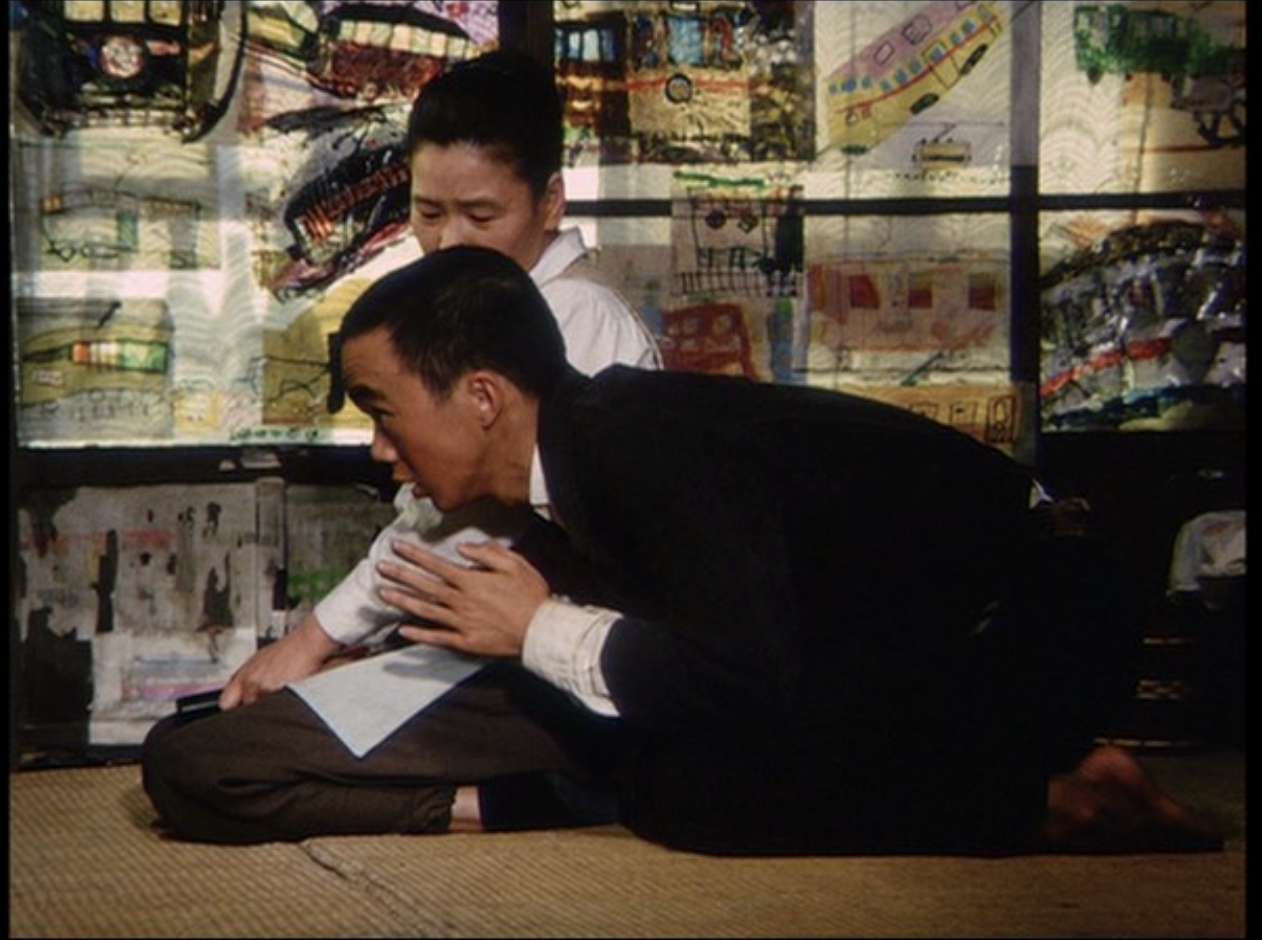

And then the third image: the boy’s drawings of streetcars papering the walls like stained glass. The room is flooded with crayon and marker, layer upon layer of imaginary transit systems. This is not décor. It is infrastructure—a world built from obsession, from rhythm, from the refusal to let imagination die. The drawings are both insulation and theology. The boy kneels in front of them not like an artist, but like a monk. It’s not just that he believes in the streetcar. It’s that the belief makes the world livable.

Kurosawa’s painted surfaces aren’t escapes from poverty—they are its mirror. But a psychic mirror, one that refuses to flatten misery into realism. Color, here, does what systems don’t: it attends. It dignifies without pity. It remains—even when everything else is rusted, broken, mute. These frames hold no illusion of repair. But they do carry something else: the persistence of vision. The sheer will to make the world visible again, even if it’s stitched from scraps, even if it’s unbearable.

In Dodes’ka-den, Kurosawa doesn’t just use color—he interrogates it. He pushes it to its edge. These aren’t “realistic” colors. They’re felt. Unbelievable. They jolt the eye, collide with mood, interrupt pity, disturb naturalism. They are color as ideogram—each frame a signifier of states beyond speech: madness, make-believe, refusal, grief. It’s as if Kurosawa asks: if black and white could tell the truth in shadow and silhouette, then what kind of truth must color tell?

He doesn’t answer. He fractures. Color here is not aesthetic—it’s epistemological. It makes us question what we see and how we interpret suffering. The colors lie and reveal at once. The sunset behind the father and child—hyper-saturated, nuclear, painted—does not represent a landscape. It exposes an internal one: memory, fantasy, the end of the world through the eyes of someone trying to survive it.

This is not color as mood board. It’s color as cognitive experiment. Kurosawa is inventing a visual language for life that refuses coherence—where death might appear bathed in orange, and madness might look like a fairytale. This is color not to enhance beauty, but to disorient moral stability. The palette doesn’t guide the viewer. It confronts them.

In this way, Dodes’ka-den anticipates the affective language of postmodern cinema: where tone and image diverge, where beauty can be cruel, and where visual excess doesn’t clarify meaning but complicates it. Harmony gives way to polyphony. The red wall is too much. The dream house glows too brightly. The streets are too yellow. The train doesn’t exist.

After Black and White: Kurosawa’s Painted Frames and the Weight of Color

The transition from black and white to color was not just technical for Kurosawa—it was ontological. In monochrome, morality could be sculpted in light and shadow. In color, morality bleeds. It blurs. And in Dodes’ka-den, it stains.

Take the image of the man carrying the child—limping across a burned orange landscape, the sky an impossible hue. This is not a natural light. It’s the light of a fable. But there’s no magic here. The man’s face is ash-covered, haggard. The boy clings to him silently. This isn’t a metaphor. It’s too literal for that. They are surviving the aftermath of a dream, walking through a color that once meant sunset, now emptied out into irradiated memory. The light is not real—but neither is the world around them. And in that contradiction, Kurosawa finds a new realism: the realism of internal ruin.

Or the image of the red “mansion,” dreamed by the man who lives in a broken-down car. Saturated in artificial orange, the house is too modern, too clean—like a 1970s toy commercial injected into the middle of despair. And yet: it’s stunning. Shot with reverence. Sparkling. Unreal. The image confronts you with the horror of desire—of believing in something so beautiful it becomes unbearable. The house isn’t tragic because it doesn’t exist. It’s tragic because it does—in him.

And then the boy’s room: papered with drawings of streetcars, every wall covered, every inch filled. The train is nowhere, but it’s everywhere. The room itself becomes a shrine to repetition, to obsession, to willful rhythm. And then there’s the shot where his mother kneels in the foreground—head bowed, surrounded by his visions. A quiet collapse within a riot of color. The sadness is not louder than the image. It’s held by it. Structured by it. This is not sympathy. This is iconography—grief rendered as devotional architecture.

One of the most brutal frames: a man, blue-faced, wide-eyed, painted by shadows and trauma. The color is grotesque, almost comic. But his stare isn’t comic. It’s cosmic—locked in a loop of hallucination and guilt. He speaks as if he’s elsewhere. The painted background behind him (tires, clouds, junk) doesn’t frame him—it collapses into him. He is both actor and canvas.

And then, always, the red room. That collage of crimson squares, cloth, paper, paint—no single shade consistent. It is not just a wall. It is labor. Someone had to make that. Had to find it, arrange it, tack it together. This is not set dressing. It is a visual manifesto. Color not as style, but as struggle.

What It Means to Watch Now

To watch Dodes’ka-den now is to fall into a dream that doesn’t comfort. It makes no argument. It makes no claim to help.

It shows what persists: scraps, gestures, rhythm, a boy walking nowhere saying dodes’ka-den, dodes’ka-den...

Not hope.Not despair.Just movement.

The world ends. The color remains.The sound repeats. The light stays strange.And the film keeps moving.