AI and the Tyranny of Common Sense: What Gets Said, What Gets Silenced

J. Owen Matson

Earlier today, a post about Andy Clark popped up in my feed here on LinkedIn—and for a moment, I felt a complicated flicker of hope.

Clark, for those unfamiliar, is a philosopher and cognitive scientist best known for the “extended mind” thesis—the idea that thinking doesn’t just happen in the brain but through our tools, environments, and interactions. His work challenges the assumption that cognition is self-contained, instead casting it as distributed, hybrid, and constantly entangled with the world.

So when someone like Clark gets cited in a conversation about AI—especially in this space—I pay attention. Not because I think he has the final word on cognition (he doesn’t), but because his work signals entry into an alternative epistemological space—one that questions the very structure of how we think about thinking.

That’s the real issue: we’re not just debating different conclusions—we’re operating in different knowledge structures.

Most public discussions around AI rely on deep, often invisible assumptions about cognition: that it’s internal, autonomous, bounded in the human. That tools are external, passive, instrumental. Even when people agree in theory that cognition is distributed or environmentally shaped, they often snap back—without realizing it—into a logic that reasserts autonomy, mastery, linear causality.

And all of this is exacerbated by platform logic. The structure of discourse on platforms like LinkedIn subtly—but powerfully—filters what kinds of thinking gain traction. Visibility is tied to clarity, brevity, certainty. The algorithm rewards what’s fast to grasp, emotionally affirming, and professionally legible. In that context, nuance becomes a liability. Ambiguity gets penalized. And anything epistemologically disruptive? It’s recoded as impractical, overly theoretical, or just noise.

So the deeper you try to go—the more you attempt to reframe the basic premises—the more likely you are to be ignored, misunderstood, or dismissed. Not because your thinking is unsound, but because the medium has already decided what counts as thought.

This isn’t a failure of intelligence. It’s what happens in an epistemological bubble: you can make perfectly sound inferences that are totally rational within a flawed frame.

And let me be clear: I don’t claim to stand outside that frame. Even after decades of thinking otherwise, I still feel its gravitational pull. The logic of cognition as autonomous, of tech as tool, of knowledge as content—these are habits of thought that reproduce themselves even in the act of questioning.

But here’s why this matters: staying in that frame distorts our ability to understand AI—not just what it does, but what kind of cognitive ecology it creates. It narrows the horizon of what we can even ask.

And in EdTech—where I’ve spent years trying to have real conversations about learning, cognition, and technology—I’ve too often found that attempts to shift the frame are met with blank stares, or worse: cheerful nods followed by a pivot back to the comfort of managerial rationality.

Or, more bluntly, outright hostility.

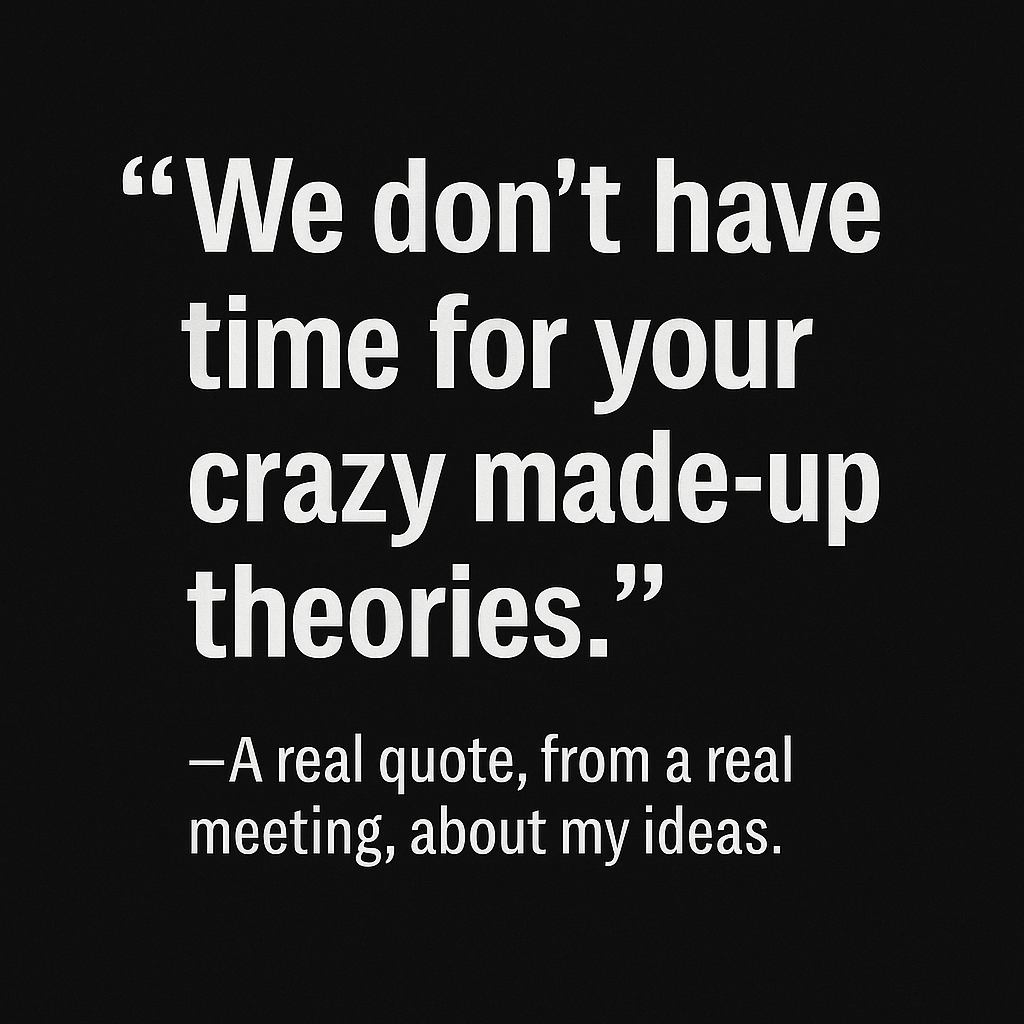

I’ve had ideas—grounded in serious interdisciplinary research—dismissed without a second thought. One response I’ll never forget:

I’ve had ideas—grounded in serious interdisciplinary research—dismissed without a second thought. One response I’ll never forget:

“We don’t have time for your crazy made-up theories.”

That’s a verbatim quote, spoken in a recorded Zoom meeting. A moment of unfiltered hostility—one that was, tellingly, edited out before the recording was distributed for review.

Let’s sit with that. Not “we disagree,” or “that doesn’t align with our goals”—but “we don’t have time.”

As if complexity is a luxury.

As if wrestling with ideas is indulgent.

As if better thinking were an obstacle to better outcomes.

And the edit wasn’t just about controlling the record—it was about controlling perception. It was about the social mechanics of epistemic enforcement. Comments like that aren’t only meant to silence an idea. They’re meant to stigmatize the person who voiced it. To signal, through tone and group complicity, that some questions are unprofessional, unserious, or dangerous to consensus.

It takes a village—not just to raise a child, but to discipline a paradigm. These aren’t isolated reactions. They are collective performances of epistemic policing, subtle and not-so-subtle cues about what kinds of thinking are welcome, and what kinds will get you quietly excluded.

Often, when people encounter frameworks that challenge their defaults—like those of Clark–. They recode them: too abstract, too academic, too elitist. That’s how the dominant system protects itself: it turns epistemological friction into a branding problem.

But the deeper issue is this:

Most mainstream conversations about AI fall—often unconsciously—into one of two frames:

- A common-sense view: AI (or language, or any tech) is a tool, used by humans to achieve predetermined ends.

- A more difficult but necessary view: technology isn’t an extension of the human—it’s constitutive of it. The human emerges through its entanglement with language, tools, infrastructures, and code.

In this second view, the boundary between “human” and “technology” becomes unstable. Language, writing, computation—they’re not accessories to thought. They are thought, differently materialized.

Yes, it’s a mind game.

But it’s also the only space in which we can begin to ask real questions about AI—not what it replaces or optimizes, but what it remakes. And what it reveals about the fragile fiction of the human as a closed, autonomous cognitive system.

If we want better conversations about AI, we need better foundations.

And that starts with refusing the comforting logic of “common sense.”